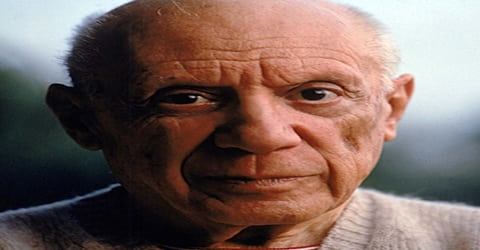

Biography of Pablo Picasso

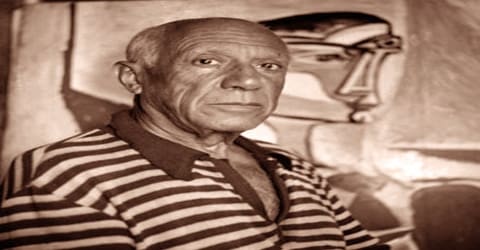

Pablo Picasso – Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet, and playwright.

Name: Pablo Ruiz Picasso

Date of Birth: 25 October 1881

Place of Birth: Málaga, Spain

Date of Death: 8 April 1973 (aged 91)

Place of Death: Mougins, France

Known for: Painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, stage design, writing

Father: José Ruiz Blasco

Mother: Maria Ruiz Picasso

Spouse: Jacqueline Roque (m. 1961–1973), Olga Khokhlova (m. 1918–1955)

Children: Paloma Picasso, Claude Pierre Pablo Picasso, Paulo Picasso, Maya Widmaier-Picasso

Early Life

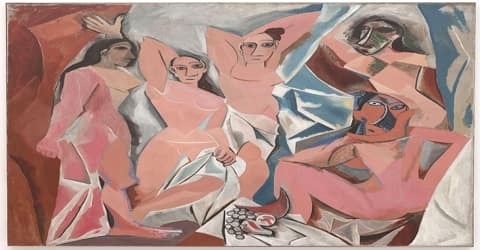

Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born on October 25, 1881, in Malaga, Spain. He was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet and playwright who spent most of his adult life in France. Regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), and Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by the German and Italian airforces during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso is not just a man and his work. Picasso is always a legend, indeed almost a myth. In the public view, he has long since been the personification of genius in modern art. Picasso is an idol, one of those rare creatures who act as crucibles in which the diverse and often chaotic phenomena of culture are focussed, who seem to body forth the artistic life of their age in one person. The same thing happens in politics, science, sport. And it happens in art.

The enormous body of Picasso’s work remains, and the legend lives on a tribute to the vitality of the “disquieting” Spaniard with the “sombre…piercing” eyes who superstitiously believed that work would keep him alive. For nearly 80 of his 91 years, Picasso devoted himself to an artistic production that contributed significantly to and paralleled the whole development of modern art in the 20th century. After 1906, the Fauvist work of the slightly older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

Picasso’s work is often categorized into periods. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period. Much of Picasso’s work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism. His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Pablo Picasso, in full Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno Crispín Crispiniano María Remedios de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz Picasso, also called (before 1901) Pablo Ruiz or Pablo Ruiz Picasso, was born in Malaga, Spain, in October of 1881, he was the first child born in the family. He has two younger sisters, Lola and Concepción. His father, José Ruiz Blasco, was a professor in the School of Arts and Crafts. Pablo’s mother was Maria Ruiz Picasso (the artist used her surname from about 1901 on). It is rumored that Picasso learned to draw before he could speak. As a child, his father frequently took him to bullfights, and one of his earlier paintings was a scene from a bullfight.

Picasso showed a passion and a skill for drawing from an early age. According to his mother, his first words were “piz, piz”, a shortening of lápiz, the Spanish word for “pencil”. From the age of seven, Picasso received formal artistic training from his father in figure drawing and oil painting. Ruiz was a traditional academic artist and instructor, who believed that proper training required disciplined copying of the masters and drawing the human body from plaster casts and live models. His son became preoccupied with art to the detriment of his classwork.

His unusual adeptness for drawing began to manifest itself early, around the age of 10, when he became his father’s pupil in A Coruña, where the family moved in 1891. From that point his ability to experiment with what he learned and to develop new expressive means quickly allowed him to surpass his father’s abilities. In A Coruña his father shifted his own ambitions to those of his son, providing him with models and support for his first exhibition there at age 13.

In 1891 the family moved to La Coruña, where, at the age of fourteen, Picasso began studying at the School of Fine Art. Under the academic instruction of his father, he developed his artistic talent at an extraordinary rate. In 1901 he went to Paris, which he found as the ideal place to practice new styles, and experiment with a variety of art forms. It was during these initial visits, which he began his work in surrealism and cubism style, which he was the founder of, and created many distinct pieces which were influenced by these art forms.

When the family moved to Barcelona, Spain, in 1896, Picasso easily gained entrance to the School of Fine Arts. A year later he was admitted as an advanced student at the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, Spain. He demonstrated his remarkable ability by completing in one day an entrance examination for which an entire month was permitted.

Picasso’s father and uncle decided to send the young artist to Madrid’s Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, the country’s foremost art school. At age 16, Picasso set off for the first time on his own, but he disliked formal instruction and stopped attending classes soon after enrollment. Madrid held many other attractions. The Prado housed paintings by Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, and Francisco Zurbarán. Picasso especially admired the works of El Greco; elements such as his elongated limbs, arresting colors, and mystical visages are echoed in Picasso’s later work.

Picasso soon found the atmosphere at the academy stifling, and he returned to Barcelona, where he began to study historical and contemporary art on his own. At that time Barcelona was the most vital cultural center in Spain, and Picasso quickly joined the group of poets, painters, and writers who gathered at the famous café Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats). Between 1900 and 1903 Picasso stayed alternately in Paris, France, and Barcelona. He had his first one-man exhibition in Paris in 1901.

Personal Life

In 1917, Pablo Picasso joined the Russian Ballet, which toured in Rome; during this time he met Olga Khoklova, who was a ballerina; the couple eventually wed in 1918, upon returning to Paris. The couple eventually separated in 1935; Olga came from nobility, and an upper-class lifestyle, while Pablo Picasso led a bohemian lifestyle, which conflicted. Although the couple separated, they remained officially married, until Olga’s death, in 1954.

In 1927, Picasso met 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter and began a secret affair with her.

Picasso had affairs with women of an even greater age disparity than his and Gilot’s. While still involved with Gilot, in 1951 Picasso had a six-week affair with Geneviève Laporte, who was four years younger than Gilot. By his 70s, many paintings, ink drawings, and prints have as their theme an old, grotesque dwarf as the doting lover of a beautiful young model. Jacqueline Roque (1927–1986) worked at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris on the French Riviera, where Picasso made and painted ceramics.

In addition to works he created of Olga, many of his later pieces also took a centralized focus on his two other love interests, Marie Theresa Walter and Dora Maar. Pablo Picasso remarried Jacqueline Roque in 1961; the couple remained married until his death 12 years later, in 1973.

In 1944, after the liberation of Paris, Picasso, then 63 years old, began a romantic relationship with a young art student named Françoise Gilot. She was 40 years younger than he was. Picasso grew tired of his mistress Dora Maar; Picasso and Gilot began to live together. Eventually, they had two children: Claude Picasso, born in 1947 and Paloma Picasso, born in 1949. In her 1964 book Life with Picasso, Gilot describes his abusive treatment and myriad infidelities which led her to leave him, taking the children with her. This was a severe blow to Picasso.

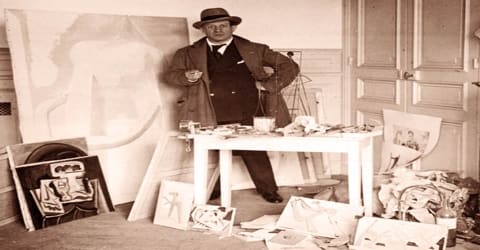

Picasso also created sculpture and prints throughout his long career and made numerous important contributions to both media. He periodically worked in ceramics and designed sets, curtains, and interiors for the theater.

Career and Works

During his stay in Paris, Pablo Picasso was constantly updating his style; he did work from the blue period, the rose period, African influenced style, to cubism, surrealism, and realism. Not only did he master these styles, he was a pioneer in each of these movements, and influenced the styles to follow throughout the 20th century, from the initial works he created. In addition to the styles he introduced to the art world, he also worked through the many different styles which appeared, while working in Paris. Not only did he continually improve his style, and the works he created, he is well known because of the fact that he had the ability to create in any style which was prominent during the time.

During 1893 the juvenile quality of his earliest work falls away, and by 1894 his career as a painter can be said to have begun. The academic realism apparent in the works of the mid-1890s is well displayed in The First Communion (1896), a large composition that depicts his sister, Lola. In the same year, at the age of 14, he painted Portrait of Aunt Pepa, a vigorous and dramatic portrait that Juan-Eduardo Cirlot has called “without a doubt one of the greatest in the whole history of Spanish painting.”

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris was the center of the international art world. In painting, it was the birthplace of the impressionists painters who depicted the appearance of objects by means of dabs or strokes of unmixed colors in order to create the look of actual reflected light. While their works retained certain links with the visible world, they exhibited a decided tendency toward flatness and abstraction.

In 1897, his realism began to show a Symbolist influence, for example, in a series of landscape paintings rendered in non-naturalistic violet and green tones. What some call his Modernist period (1899–1900) followed. His exposure to the work of Rossetti, Steinlen, Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch, combined with his admiration for favorite old masters such as El Greco, led Picasso to a personal version of modernism in his works of this period.

Goya, for instance, was an artist whose works Picasso copied in the Prado in 1898 (a portrait of the bullfighter Pepe Illo and the drawing for one of the Caprichos, Bien tirada está, which shows a Celestina checking a young maja’s stockings). Those same characters reappear in his late work Pepe Illo in a series of engravings (1957) and Celestina as a kind of voyeuristic self-portrait, especially in the series of etchings and engravings known as Suite 347 (1968).

Picasso made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe, in 1900. There, he met his first Parisian friend, journalist and poet Max Jacob, who helped Picasso learn the language and its literature. Soon they shared an apartment; Max slept at night while Picasso slept during the day and worked at night. These were times of severe poverty, cold, and desperation. Much of his work was burned to keep the small room warm. During the first five months of 1901, Picasso lived in Madrid, where he and his anarchist friend Francisco de Asís Soler founded the magazine Arte Joven (Young Art), which published five issues. Soler solicited articles and Picasso illustrated the journal, mostly contributing grim cartoons depicting and sympathizing with the state of the poor. The first issue was published on 31 March 1901, by which time the artist had started to sign his work Picasso; before he had signed Pablo Ruiz y Picasso.

In Barcelona Picasso moved among a circle of Catalan artists and writers whose eyes were turned toward Paris. Those were his friends at the café Els Quatre Gats (“The Four Cats,” styled after the Chat Noir (“Black Cat”) in Paris), where Picasso had his first Barcelona exhibition in February 1900, and they were the subjects of more than 50 portraits (in mixed media) in the show. In addition, there was a dark, moody “modernista” painting, Last Moments (later painted over), showing the visit of a priest to the bedside of a dying woman, a work that was accepted for the Spanish section of the Exposition Universelle in Paris in that year. Eager to see his own work in place and to experience Paris firsthand, Picasso set off in the company of his studio-mate Carles Casagemas (Portrait of Carles Casagemas (1899)) to conquer, if not Paris, at least a corner of Montmartre.

Picasso’s Blue Period (1901–1904), characterized by sombre paintings rendered in shades of blue and blue-green, only occasionally warmed by other colors, began either in Spain in early 1901, or in Paris in the second half of the year. Many paintings of gaunt mothers with children date from the Blue Period, during which Picasso divided his time between Barcelona and Paris. In his austere use of color and sometimes doleful subject matter – prostitutes and beggars are frequent subjects – Picasso was influenced by a trip through Spain and by the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas. Starting in autumn of 1901 he painted several posthumous portraits of Casagemas, culminating in the gloomy allegorical painting La Vie (1903), now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

In the second half of 1904, Picasso’s style took a new direction. In these paintings, the color became more natural, delicate, and tender in its range, with reddish and pink tones dominating the works. Thus this period was called his Pink Period. The most celebrated example of this phase is the Family of Saltimbanques (1905). Picasso’s work between 1900 and 1905 was generally flat, emphasizing the two-dimensional character of the painting surface. Late in 1905, however, he became increasingly interested in pictorial volume. This interest seems to have been influenced by the late paintings of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906).

The face in Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906) reveals still another new interest: its mask-like abstraction was inspired by Iberian sculpture, an exhibition of which Picasso had seen at the Louvre, in Paris, in the spring of 1906. This influence reached its fullest expression a year later in one of the most revolutionary pictures of Picasso’s entire career, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).

(Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Museum of Modern Art, New York)

His violent treatment of the female body and masklike painting of the faces (influenced by a study of tribal art, which a few critics later called the Negro, or African, Period) have made that work controversial. Yet the work was firmly based upon art-historical tradition: a renewed interest in El Greco contributed to the fracturing of the space and the gestures of the figures, and the overall composition owed much to Paul Cézanne’s Bathers as well as to J.-A.-D. Ingres’s harem scenes. The Demoiselles, however later named to refer to Avignon Street in Barcelona, where sailors found popular brothels was perceived as a shocking and direct assault: the women were not conventional images of beauty but prostitutes who challenged the very tradition from which they were born. Although he had his collectors by that date (Americans Leo and Gertrude Stein and the Russian merchant Sergey Shchukin) and soon a dealer (Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler), Picasso chose to roll up the canvas of the Demoiselles and to keep it out of sight for several years.

When he displayed the painting to acquaintances in his studio later that year, the nearly universal reaction was shock and revulsion; Matisse angrily dismissed the work as a hoax. Picasso did not exhibit Le Demoiselles publicly until 1916. Other works from this period include Nude with Raised Arms (1907) and Three Women (1908).

In 1907, Picasso joined an art gallery that had recently been opened in Paris by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Kahnweiler was a German art historian and art collector who became one of the premier French art dealers of the 20th century. He was among the first champions of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and the Cubism that they jointly developed. Kahnweiler promoted burgeoning artists such as André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Fernand Léger, Juan Gris, Maurice de Vlaminck and several others who had come from all over the globe to live and work in Montparnasse at the time.

In 1908 the African-influenced striations and masklike heads were superseded by a technique that incorporated elements he and his new friend Georges Braque found in the work of Cézanne, whose shallow space and characteristic planar brushwork are especially evident in Picasso’s work of 1909. Still lifes, inspired by Cézanne, also became an important subject for the first time in Picasso’s career. Cubist heads of Fernande include the sculpture Head of a Woman (1909) and several paintings related to it, including Woman with Pears (1909).

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is generally regarded as the first cubist painting. The faces of the figures are seen from both front and profile positions at the same time. Between 1907 and 1911 Picasso continued to break apart the visible world into increasingly small facets of monochromatic (using one color) planes of space. In doing so, his works became more and more abstract. Representation gradually vanished from his painting, until it became an end in itself—for the first time in the history of Western art.

Analytic cubism (1909–1912) is a style of painting Picasso developed with Georges Braque using monochrome brownish and neutral colors. Both artists took apart objects and “analyzed” them in terms of their shapes. Picasso and Braque’s paintings at this timeshare many similarities. In 1911, Picasso was arrested and questioned about the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre. Suspicion for the crime had initially fallen upon Apollinaire due to his links to Géry Pieret, an artist with a history of thefts from the gallery. Apollinaire, in turn, implicated his close friend Picasso, who had also purchased stolen artworks from the artist in the past. Afraid of a conviction that could result in his deportation to Spain, Picasso denied having ever met Apollinaire. Both were later cleared of any involvement in the painting’s disappearance.

The growth of this process is evident in all of Picasso’s work between 1907 and 1911. Some of the most outstanding pictorial examples of the development are Fruit Dish (1909), Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910), and Ma Jolie, also known as Woman with a Guitar (1911–12).

Synthetic cubism (1912–1919) was a further development of the genre of cubism, in which cut paper fragments often wallpaper or portions of newspaper pages were pasted into compositions, marking the first use of collage in fine art.

In February 1917, Picasso made his first trip to Italy. In the period following the upheaval of World War I, Picasso produced work in a neoclassical style. This “return to order” is evident in the work of many European artists in the 1920s, including André Derain, Giorgio de Chirico, Gino Severini, Jean Metzinger, the artists of the New Objectivity movement and of the Novecento Italiano movement. Picasso’s paintings and drawings from this period frequently recall the work of Raphael and Ingres.

After Picasso experimented with the new medium of college, he returned more intensively to painting. In his Three Musicians (1921), the planes became broader, more simplified, and more colorful. In its richness of feeling and balance of formal elements, the Three Musicians represents a classical expression of cubism.

Between 1915 and 1917, Picasso began a series of paintings depicting highly geometric and minimalist Cubist objects, consisting of either a pipe, a guitar or a glass, with an occasional element of college. “Hard-edged square-cut diamonds”, notes art historian John Richardson, “these gems do not always have upside or downside”. “We need a new name to designate them,” wrote Picasso to Gertrude Stein: Maurice Raynal suggested “Crystal Cubism”. These “little gems” may have been produced by Picasso in response to critics who had claimed his defection from the movement, through his experimentation with classicism within the so-called return to order following the war.

About 1915, and again in the early 1920s, he turned away from abstraction and produced drawings and paintings in a realistic and serenely beautiful classical style. One of the most famous of these works is the Woman in White (1923). Painted just two years after the Three Musicians, the quiet and unobtrusive (not calling attention to itself) elegance of this masterpiece testifies to the ease with which Picasso could express himself pictorially.

Pablo Picasso was a pacifist, and large-scale paintings he created, showcased this cry for peace, and change during the time. A 1937 piece he created, after the German bombing of Guernica, was one such influential piece of the time. Not only did this become his most famous piece of artwork, but the piece which showed the brutality of war, and death, also made him a prominent political figure of the time. To sell his work, and the message he believed in, art, politics, and eccentricity, were among his main selling points.

One of Picasso’s most celebrated paintings of the 1930s is Guernica (1937). This work had been commissioned for the Spanish Government Building at the Paris World’s Fair. It depicts the destruction by bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39; the military revolt against the Spanish government). The artist’s deep feelings about the work, and about the massacre (a mass killing) which inspired it, are reflected in the fact that he completed the work, that is more than 25 feet wide and 11 feet high, within six or seven weeks.

(Guernica, 1937, Museo Reina Sofia)

Guernica is an extraordinary monument within the history of modern art. Executed entirely in black, white, and gray, it projects an image of pain, suffering, and brutality that has few parallels. Picasso applied the pictorial language of cubism to a subject that springs directly from social and political awareness.

In 1939 and 1940, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, under its director Alfred Barr, a Picasso enthusiast, held a major retrospective of Picasso’s principal works until that time. This exhibition lionized the artist, brought into full public view in America the scope of his artistry, and resulted in a reinterpretation of his work by contemporary art historians and scholars. According to Jonathan Weinberg, “Given the extraordinary quality of the show and Picasso’s enormous prestige, generally heightened by the political impact of Guernica … the critics were surprisingly ambivalent”. Picasso’s “multiplicity of styles” was disturbing to one journalist, another described the artist as “wayward and even malicious”; Alfred Frankenstein’s review in ARTnews concluded that Picasso was both charlatan and genius.

Picasso also declared publicly in 1947 that he was a Communist (someone who believes the national government should control all businesses and the distribution of goods). When he was asked why he was a Communist, he stated, “When I was a boy in Spain, I was very poor and aware of how poor people had to live. I learned that the Communists were for the poor people. That was enough to know. So I became for the Communists.” But sometimes the Communist cause was not as keen on Picasso as Picasso was about being a Communist. A 1953 portrait he painted of Joseph Stalin (1879–1953) caused an uproar in the Communist Party’s leadership. The Soviet government banished his works.

During the Second World War, Picasso remained in Paris while the Germans occupied the city. Picasso’s artistic style did not fit the Nazi ideal of art, so he did not exhibit during this time. He was often harassed by the Gestapo. During one search of his apartment, an officer saw a photograph of the painting Guernica. “Did you do that?” the German asked Picasso. “No,” he replied, “You did”.

Retreating to his studio, he continued to paint, producing works such as the Still Life with Guitar (1942) and The Charnel House (1944–48). Although the Germans outlawed bronze casting in Paris, Picasso continued regardless, using bronze smuggled to him by the French Resistance.

Around this time, Picasso wrote poetry as an alternative outlet. Between 1935 and 1959 he wrote over 300 poems. Largely untitled except for a date and sometimes the location of where it was written (for example “Paris 16 May 1936”), these works were gustatory, erotic and at times scatological, as were his two full-length plays Desire Caught by the Tail (1941) and The Four Little Girls (1949).

Although Picasso had been in exile from his native Spain since the 1939 victory of Generalissimo Francisco Franco (1892–1975), he gave eight hundred to nine hundred of his earliest works to the city and people of Barcelona. To display these works, the Palacio Aguilar was renamed the Picasso Museum and the works were moved inside. But because of Franco’s dislike for Picasso, Picasso’s name never appeared on the museum.

Following the end of WWII, Pablo Picasso turned back towards his classic style of work, and he created the “Dove of Peace.” Even though he became a member of the Communist party, and supported Stalin and his political views and rule, Pablo Picasso could do no wrong. In the eyes of his admirers and supporters, he was still a prominent figure, and one which they would follow, regardless of what wrongs he did. He was not only an influence because of the works he created, but he was also an influential figure in the political realm.

Picasso’s final works were a mixture of styles, his means of expression in constant flux until the end of his life. Devoting his full energies to his work, Picasso became more daring, his works more colorful and expressive, and from 1968 to 1971 he produced a torrent of paintings and hundreds of copperplate etchings. At the time these works were dismissed by most as pornographic fantasies of an impotent old man or the slapdash works of an artist who was past his prime. Only later, after Picasso’s death, when the rest of the art world had moved on from abstract expressionism, did the critical community come to see the late works of Picasso as prefiguring Neo-Expressionism.

Although Pablo Picasso is mainly known for his influence on the art world, he was an extremely prominent figure during his time, and to the 20th century in general. He spread his influences to the art world, but also to many aspects of the cultural realm of life as well. He played several roles in a film, where he always portrayed himself; he also followed a bohemian lifestyle and seemed to take liberties as he chose, even during the later stages of his life. He even died in style, while hosting a dinner party in his home.

Death and Legacy

Pablo Picasso died on 8 April 1973 in Mougins, France from pulmonary edema and heart failure, while he and his wife Jacqueline entertained friends for dinner. He was interred at the Château of Vauvenargues near Aix-en-Provence, a property he had acquired in 1958 and occupied with Jacqueline between 1959 and 1962. Jacqueline Roque prevented his children Claude and Paloma from attending the funeral. Devastated and lonely after the death of Picasso, Jacqueline Roque killed herself by gunshot in 1986 when she was 59 years old.

Pablo Picasso is recognized as the world’s most prolific painter. His career spanned over a 78 year period, in which he created: 13,500 paintings, 100,000 prints and engravings, and 34,000 illustrations which were used in books. He also produced 300 sculptures and ceramic pieces during this expansive career. It is also estimated that over 350 pieces which he created during his career, have been stolen; this is a figure that is far higher than any other artist throughout history.

Pablo Picasso has also sold more pieces, and his works have brought in higher profit margins, than any other artist of his time. His pieces rank among the most expensive artworks to be created; with a price tag of $104 million, Garson a la Pipe was sold in 2004.

Picasso entrusted Christian Zervos to constitute the catalog raisonné of his work (painted and drawn). The first volume of the catalog, Works from 1895 to 1906, published in 1932, entailed the financial ruin of Zervos, self-publishing under the name Cahiers d’art, forcing him to sell part of his art collection at auction to avoid bankruptcy.

From 1932 to 1978, Zervos constituted the catalog raisonné of the complete works of Picasso in the company of the artist who had become one of his friends in 1924. Following the death of Zervos, Mila Gagarin supervised the publication of 11 additional volumes from 1970 to 1978.

Information Source: