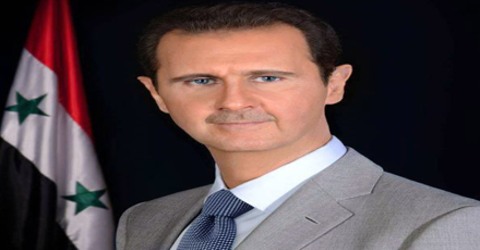

Bashar al-Assad – 19th President of Syria

Full name: Bashar Hafez al-Assad

Date of birth: 11 September 1965 (age 51)

Place of birth: Damascus, Syria

Political party: Syrian Ba’ath Party

Other political affiliations: National

Religion: Islam (Alawite)

Father: Hafez al-Assad

Mother: Aniseh al-Assad

Siblings: Bassel al-Assad, Maher al-Assad, Bushra al-Assad, Majd al-Assad

Spouse: Asma al-Assad (m. 2000)

Children: Zein al-Assad, Karim al-Assad, Hafez al-Assad

Early Life

Bashar al-Assad was born on September 11, 1965, in Damascus, Syria. He is a Syrian president from 2000. He succeeded his father, Ḥafiz al-Assad, who had ruled Syria since 1971. In spite of early hopes that his presidency would usher in an era of democratic reform and economic revival, Bashar al-Assad largely continued his father’s authoritarian methods. Beginning in 2011, Assad faced a major uprising in Syria that evolved into a civil war.

In 1994, after his elder brother Bassel died in a car crash, Bashar was recalled to Syria to take over Bassel’s role as heir apparent. He entered the military academy, taking charge of the Syrian occupation of Lebanon in 1998. On 10 July 2000, Assad was elected as President, succeeding his father, who died in office a month prior. In the 2000 and subsequent 2007 election, he received 99.7% and 97.6% support, respectively, in referendums on his leadership.

On 16 July 2014, Assad was sworn in for another seven-year term after taking 88.7% of votes in the first contested presidential election in Ba’athist Syria’s history. The election was criticised by media outlets as “tightly controlled” and without independent election monitors, while an international delegation led by allies of Assad issued a statement asserting that the election was “free, fair and transparent”. The Assad government describes itself as secular, while some experts claim that the government exploits sectarian tensions in the country and relies upon the Alawite minority to remain in power.

In recent years his government faced a major uprising in Syria that evolved into a civil war, and despite international protests, he has continued to demonstrate tremendous disregard for human life in his efforts to hold onto power. In spite of promising to be a transformational figure who would propel Syria into the 21st century, he failed, and has instead followed in the footsteps of his father.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Bashar al-Assad was born on September 11, 1965, in Damascus, Syria, to Hafez al-Assad, and his wife, Aniseh. Al-Assad in Arabic means “the Lion”; Assad’s peasant paternal grandfather had changed the family name from Wahsh (meaning “Savage” or “Monster”) upon acquiring minor noble status in 1927. He is the second son among the five children of his parents. His father was a politician who eventually rose to become the President of Syria. He had an older brother, Bassel, who later died in a car accident.

Assad had five siblings, three of whom are deceased. A sister named Bushra died in infancy. Assad’s youngest brother, Majd, was not a public figure and little is known about him other than he was intellectually disabled, and died in 2009 after a “long illness”. Unlike his brothers Bassel and Maher, and second sister, also named Bushra, Bashar was quiet, reserved and lacked interest in politics or the military.

Bashar grew up quiet and reserved, in the shadow of his more dynamic and outgoing brother, Bassel. Educated at the Arab-French al Hurriya School in Damascus, Bashar learned to speak fluent English and French. He graduated from high school in 1982, and went on to study medicine at the University of Damascus, graduating in 1988. He conducted his residency in ophthalmology at the Tishreen military hospital outside of Damascus, and then traveled to Western Eye Hospital in London, England in 1992.

Personal Life

In December 2000, he married Asma Assad, a British woman of Syrian origin from London. In 2001, Asma gave birth to their first child, a son named Hafez after the child’s grandfather Hafez al-Assad. Their daughter Zein was born in 2003, followed by their second son Karim in 2004.

Assad’s sister Bushra al-Assad and mother Anisa Makhlouf left Syria in 2012 and 2013 respectively to live in the United Arab Emirates. Makhlouf died in Dubai in 2016.

Early Political Career

In 1994, his elder brother, Bassel—his father’s heir apparent—was killed in a car accident. Bashar was summoned to Damascus by his father, Hafez, who systematically started preparing Bashar for succeeding him as the President of Syria.

Bashar entered the military academy at Homs, located north of Damascus, and was quickly pushed through the ranks to become a colonel in just five years. During this time, he served as an advisor to his father, hearing complaints and appeals from citizens, and led a campaign against corruption. As a result, he was able to remove many potential rivals.

Presidency Career

Hafez al-Assad died on June 10, 2000. In the days following his death, Syria’s parliament quickly voted to lower the minimum age for presidential candidates from 40 to 34, so that Bashar could be eligible for the office. Ten days after Hafez’s death, Bashar al-Assad was chosen for a seven-year term as president of Syria. In a public referendum, running unopposed, he received 97 percent of the vote. He was also selected leader of the Ba’ath Party and commander in chief of the military.

Bashar was considered a younger-generation Arab leader, who would bring change to Syria, a region long filled with aging dictators. He was well-educated, and many believed he would be capable of transforming his father’s iron-rule regime into a modern state. Influenced by his western education and urban upbringing, Bashar initially seemed eager to implement a cultural revolution in Syria. He stated early on that democracy was “a tool to a better life,” though he added that democracy couldn’t be rushed in Syria. In his first year as president, he promised to reform the corruption in the government, and spoke of moving Syria toward the computer technology, internet and cell phones of the 21st century.

In his first year as president, he promised to reform the corrupt government of Syria, and spoke of moving his country towards modernization.

At the end of his first year as president, many of his promised economic reforms were yet to materialize. The largely corrupt government bureaucracy made it difficult for the private sector to emerge, and he seemed incapable of making the necessary systemic changes.

He maintained his father’s firm stance in Syria’s decades-long conflict with Israel, allegedly giving support to Palestinian and Lebanese militant groups. For nearly a decade, he successfully suppressed internal dissention, due mostly to the close relationship between the Syrian military and intelligence agencies.

In international affairs, Bashar was confronted with many of the issues his father faced: a volatile relationship with Israel, military occupation in Lebanon, tensions with Turkey over water rights, and the insecure feeling of being a marginal influence in the Middle East. Most analysts contend that Bashar continued his father’s foreign policy, providing direct support to militant groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad, though Syria officially denied this.

Though a gradual withdrawal from Lebanon began in 2000, it was quickly hastened after Syria was accused of involvement in the assassination of former Lebanese premier Rafik Hariri. The accusation led to a public uprising in Lebanon, as well as international pressure to remove all troops. Since then, relations with the West and many Arab states have deteriorated, and it seems that Syria’s only friend in the Middle East is Iran.

Despite promises of human rights reform, not much has changed since Bashar al-Assad took office. For nearly a decade, he successfully suppressed internal dissention, due mostly to the close relationship between the Syrian military and intelligence agencies. In 2006, Syria expanded its use of travel bans against dissidents, preventing many from entering or leaving the country.

In 2007, he was re-elected by a nearly unanimous majority for a second term as president. His critics and opponents alleged that the elections were rigged.

In 2008, and again in 2011, social media sites such as YouTube and Facebook were blocked. Human rights groups have reported that political opponents of Bashar al-Assad are routinely tortured, imprisoned and killed.

In January 2011, following the pro-democracy uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, protests began in Syria, demanding political reforms, a reinstatement of civil rights and an end to the state of emergency, which had been in place since 1963.

In May 2011, the Syrian military retorted with violent protests in the town of Homs and the suburbs of Damascus. The following month, he promised a national dialogue and new parliamentary elections, but no change came, and the protests continued.

By the late 2011, many countries called for his resignation and the Arab League suspended Syria, which forced the Syrian government to agree to allow Arab observers into the country.

In January 2012, the Reuters News Agency reported that more than 5,000 civilians had been killed by the Syrian militia (Shabeeha), and that 1,000 people had been killed by anti-regime forces. That March, the United Nations endorsed a peace plan that was drafted by former UN Secretary Kofi Annan, but this didn’t stop the violence.

In June 2012, a UN official stated that the uprisings had transitioned into a full-scale civil war. The conflict continues, with daily reports of the killing of scores of civilians by government forces, and counter-claims by the al-Assad regime of the killings beging staged or the result of outside agitators.

In 2013, his government used chemical weapons against civilians which resulted in the deaths of hundreds including women and children. It prompted a debate among some Western countries over what steps should be taken against him and his regime.

In August 2013, he has come under fire from leaders around the world, including U.S. president Barack Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron, for using chemical weapons against civilians. This action resulted in the deaths of women and children, and some Western countries are debating what steps should be taken against al-Assad and his regime.

After the fall of four military bases in September 2014, which were the last government footholds in the al-Raqqah Governorate, Assad received significant criticism from his Alawite base of support. This included remarks made by Douraid al-Assad, cousin of Bashar al-Assad, demanding the resignation of the Syrian Defence Minister, Fahd Jassem al-Freij, following the massacre by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant of hundreds of government troops captured after the ISIL victory at Tabqa Air base.

In 2015, several members of the Assad family died in Latakia under unclear circumstances. On 14 March, an influential cousin of Assad and founder of the shabiha, Mohammed Toufic al-Assad, was assassinated with five bullets to the head in a dispute over influence in Qardaha—the ancestral home of the Assad family. In April 2015, Assad ordered the arrest of his cousin Munther al-Assad in Alzirah, Latakia. It remains unclear whether the arrest was due to actual crimes.

Assad condemned the November 2015 Paris attacks, but added that France’s support for Syrian rebel groups had contributed to the spread of terrorism, and rejected sharing intelligence on terrorist threats with French authorities unless France altered its foreign policy on Syria.

In 2016, Syrian Democratic Forces found paperwork at a recently captured oil refinery during the al-Shaddadi offensive suggesting that ISIS had sold oil directly to the Assad regime, with a SDF commander stating; “The regime says that it’s fighting terrorists, but it’s not really. In fact, it’s always maintained economic ties. Bashar Assad controls nothing anymore and he has a massive logistical lead in terms of oil especially so he’s bought oil from the jihadists, and in return, he’s supplied them with weapons”.

Even today, the conflict continues with daily reports of the killing of scores of civilians by government forces, and counter-claims by the al-Assad regime of the killings being staged.

With rebels and government troops seemingly locked in a bloody deadlock and security conditions deteriorating day by day, his public appearances have become increasingly rare and consist mainly of staged events to rally troops and civilian supporters.