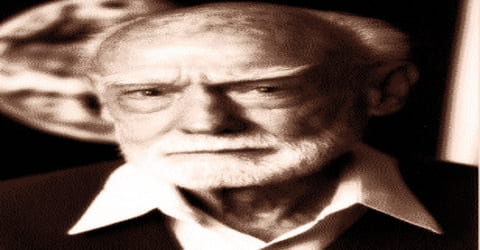

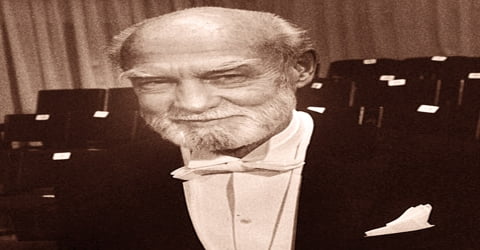

Biography of Roger Wolcott Sperry

Roger Wolcott Sperry – American neuropsychologist, neurobiologist and Nobel laureate.

Name: Roger Wolcott Sperry

Date of Birth: August 20, 1913

Place of Birth: Hartford, Connecticut, United States

Date of Death: April 17, 1994 (aged 80)

Place of Death: Pasadena, California, United States

Occupation: Neuropsychologist

Father: Francis Bushnell Sperry

Mother: Florence Kraemer Sperry

Spouse/Ex: Norma Gay Deupree (m. 1949)

Children: Glenn Michael, Janeth Hope

Early Life

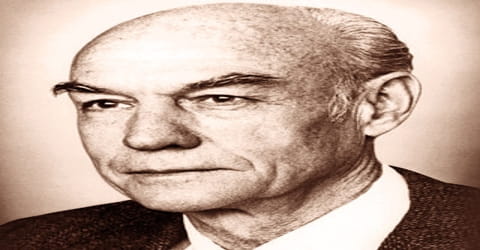

An American neurobiologist, corecipient with David Hunter Hubel and Torsten Nils Wiesel of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1981 for their investigations of brain function, Sperry in particular for his study of functional specialization in the cerebral hemispheres, Roger Wolcott Sperry was born on August 20, 1913, in Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. to Francis Bushnell and Florence Kraemer Sperry. According to a survey done by the noted scientific journal, Review of General Psychology, he was the 44th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.

Although Sperry entered college with English as his major he quickly became interested in psychology and after graduation, switched his subject to earn his M.A. in psychology and Ph.D. in zoology. From the beginning, he worked on the brain, first with rats, then with salamanders, newts, and cats. However, his studies of epileptic patients with split-brain earned the greatest fame. His experiments not only established that the corpus callosum, which joins the two hemisphere of the brain, functions as a channel to pass information between the two hemispheres, but also that each hemisphere of the brain undertakes specific functions. The work overturned the prevailing idea that the left side of the brain is more dominant than the others. He was also a skillful experimentalist and often undertook very clever operations in course of his experiments. Although disease made him physically immobile he remained intellectually active till his last and contributed much to human knowledge.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

A noted neuropsychologist and neurobiologist, Roger Wolcott Sperry was born on August 20, 1913, in Hartford, Connecticut. His father, Francis Bushnell Sperry, was a banker while his mother, Florence Kraemer Sperry, was trained in business school. He had a younger brother, Russell Loomis Sperry, who grew up to be a chemist. He was raised in an upper-middle-class environment, which stressed academic achievement. Roger’s father died when he was just eleven years old. To support the family, his mother accepted employment in the local high school as an assistant to the principal.

Sperry went to Hall High School in West Hartford, Connecticut, where he was a star athlete in several sports, and did well enough academically to win a scholarship to Oberlin College. At Oberlin, he was captain of the basketball team, and he also took part in varsity baseball, football, and track. He also worked at a cafe on campus to help support himself. He received his bachelor’s degree in English in 1935 and a master’s degree in psychology in 1937.

Sperry earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature and a master’s degree in psychology from Oberlin (Ohio) College and a doctorate in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1941. He then became an associate of Karl Lashley, first at Harvard University and then at the Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology in Orange Park, Fla. In 1946 he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago and in 1954 moved to the California Institute of Technology as Hixon professor of psychobiology.

As part of his doctoral work, Sperry took nerves from right hind legs of the rats and placed them in the left hind legs of other rats and vice verse. He then subjected them to electric shock and found that if the shock was applied to the left paw, the rat would lift its right paw and vice verse. After repeated experiments, Sperry came to the conclusion that something can never be learned. His doctoral dissertation was titled ‘Functional results of crossing nerves and transposing muscles in the fore and hind limbs of the rat’.

Personal Life

In 1949, Roger Wolcott Sperry married Norma Gay Deupree. They had one son, Glenn Michael, and one daughter, Janeth Hope.

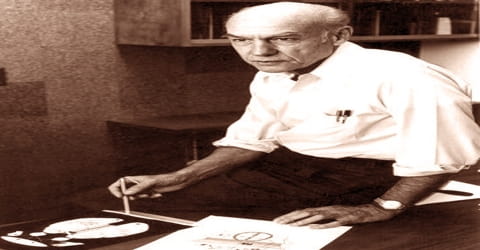

Sperry was an enthusiastic paleontologist and had a large collection of fossils. He was also an excellent sculptor and loved to work with ceramics. Going on camping and fishing trips with his family was another of his favorite pastime. Sperry was a quiet, thoughtful, and modest man with an insatiable curiosity. He never stopped working, questioning, or learning up until his death in 1994 of ALS or Lou Gehrig’s Disease. Sperry could often be found in his office with his feet propped up on his desk scribbling in his notebook or deep in thought.

Career and Works

In 1942, Roger Wolcott Sperry began work at the Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology, then a part of Harvard University. There he focused on experiments involving the rearranging of motor and sensory nerves. He left in 1946 to become an assistant professor, and later associate professor, at the University of Chicago. In 1949, during a routine chest x-ray, there was evidence of tuberculosis. He was sent to Saranac Lake in the Adironack Mountains in New York for treatment. It was during this time when he began writing his concepts of the mind and brain and was first published in the American Scientist in 1952.

However, prior to that, in 1951, he had established the Chemoaffinity hypothesis, which states that the initial wiring diagram of an organism is determined by the genetic makeup of its cell. Also in 1952, Sperry became the Section Chief of Neurological Diseases and Blindness at the National Institutes of Health and later in the year, joined Marine Biology Laboratory in Coral Gables, Florida. He then returned to University of Chicago as Associate Professor of Psychology and remained there till 1953. Sometimes now, he was offered the post of Hixson Professor of Psychobiology at California Institute of Technology. Therefore, in 1954, he shifted to California, where he continued with his work on the regeneration of nerve fibers.

In 1954, Sperry accepted the position as a professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech as Hixson Professor of Psychobiology) where he performed his most famous experiments with Joseph Bogen, MD and many students including Michael Gazzaniga. Under the supervision of Paul Weiss, while earning his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, Sperry became interested in neuronal specificity and brain circuitry and began questioning the existing concepts about these two topics. He began a series of experiments in an attempt to answer this question. Sperry cross-wired the motor nerves of rats’ legs so the left nerve controlled the right leg and vice versa. He would then place the rats in a cage that had an electric grid on the bottom separated into four sections. Each leg of the rat was placed into one of the four sections of the electric grid. A shock was administered to a specific section of the grid, for example, the grid where the rat’s left back leg was located would receive a shock. Every time the left paw was shocked the rat would lift his right paw and vice versa. Sperry wanted to know how long it would take the rat to realize he was lifting the wrong paw. After repeated tests Sperry found that the rats never learned to lift up the correct paw, leading him to the conclusion that some things are just hardwired and cannot be relearned. In Sperry’s words, “no adaptive functioning of the nervous system took place.”

Sperry’s early research was on the regeneration of nerve fibers. He eventually became interested in brain function and undertook research on animals and then on human epileptics whose brains had been “split” i.e., in whom the thick cable of nerves (the corpus callosum) connecting the right and left cerebral hemispheres had been severed. His studies demonstrated that the left side of the brain is normally dominant for analytical and verbal tasks, while the right hemisphere assumes dominance in spatial tasks, music, and certain other areas. The surgical and experimental techniques Sperry developed from the late 1940s laid the groundwork for much more specialized explorations of the mental functions carried out in different areas of the brain.

Sperry then proceeded to teach the cats to distinguish between squares and triangles first with the right eye and then with left eye covered. Their response led him to believe that the left and right hemispheres of the brain function independently. Next, he began to work with epileptic patients, whose corpus callosum had been severed in order to contain the ailment. This work not only helped to understand the lateralization of brain function to a great extent but at a personal level, it earned him the coveted Nobel Prize.

Sperry first became interested in “split-brain” research when he was working on the topic of interocular transfer, which occurs when “one learns with one eye how to solve a problem then, with that eye covered and using the other eye, one already knows how to solve the problem”. research with “split-brain” cats helped lead to the discovery that cutting the corpus callosum is a very effective treatment for patients who suffer from epilepsy. Initially, after the patients recovered from surgery, there were no signs that the surgery caused any changes to their behavior or functioning. This observation rendered the question: if the surgery had absolutely no effect on any part of the patients’ normal functioning then what is the purpose of the corpus callosum? Was it simply there to keep the two sides of the brain from collapsing, as Karl Lashley jokingly put it? Sperry was asked to develop a series of tests to perform on the “split-brain” patients to determine if the surgery caused changes in the patients’ functioning or not.

Sperry also found that each half of the brain performs a specialized task. The left hemisphere is dominant over analytical and verbal tasks such as writing, speaking, mathematical calculation, reading while the right hemisphere handles spatial, visual, and emotional tasks such as problem-solving, recognizing faces, symbolic reasoning, art, etc.

In the words of a 2009 review article in Science magazine: “He suggested that gradients of such identification tags on retinal neurons and on the target cells in the brain coordinately guide the orderly projection of millions of developing retinal axons. This idea was supported by the identification and genetic analysis of axon guidance molecules, including those that direct development of the vertebrate visual system.” This was confirmed in the seventies by Marshall W. Nirenberg’s work on chick retinas and later on Drosophila melanogaster larvae. The experiments conducted by Sperry focused on four major ideas which were also called “turnarounds”: equipotentiality, split-brain studies, nerve regeneration and plasticity, and psychology of the consciousness.

During later years, Sperry turned away from experimental science and began developing a theory on consciousness. He also worked to develop science based on ethical values. His last published book was ‘Science and Moral Priority: Merging Mind, Brain, and Human Values’ (1983). Sperry remained at the California Institute of Technology until 1984. Later, he served on the Board of Trustees and as Professor of Psychobiology Emeritus at the institute. However, he never stopped working and was often found at his office deeply thinking or jotting down his thought in his notebook.

Awards and Honor

Roger Wolcott Sperry was granted numerous awards over his lifetime, including the California Scientist of the Year Award in 1972, the National Medal of Science in 1989, the Wolf Prize in Medicine in 1979, and the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award in 1979.

In 1981, Rodney Wolcott Sperry received one half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries concerning the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres”. The other half was jointly shared by David H. Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel “for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system”.

Death and Legacy

Towards the end of his life, he started suffering from a degenerative neuromuscular disease. Roger Wolcott Sperry died on April 17, 1994, due to heart failure, at Pasadena, California.

His pioneering work on the African Clawed Frog, which resulted in the start of the Chemoaffinity Hypothesis, is one his most important works. He removed the eye of a frog and after rotating it 180 degrees replaced it in such a way that ventral part of the eye was positioned at the top and the dorsal was positioned at the bottom. Very soon the nerves were regenerated. But, when the food source placed above the frog, it flipped its tongue downwards. After repeated experiments, he came to the conclusion that the optic nerve, which transfers visual experience from retina to brain and neuron in the tectum region of the brain, used a chemical marker, which influenced their connectivity.

Sperry is best known for his work on the split brain. In general, the left and right hemisphere of the brain is connected with the corpus callosum. While working the cats, he had found that if the corpus callosum is severed the two hemispheres of the brain can act independently.

Information Source: