Biography of Mary Seacole

Mary Seacole – British-Jamaican businesswoman and nurse.

Name: Mary Jane Seacole (née Grant)

Date of Birth: November 23, 1805

Place of Birth: Kingston, Jamaica

Date of Death: 14 May 1881 (aged 75)

Place of Death: Paddington, London, England

Occupation: Nurse, Hotelier, Boarding house keeper, Author, World traveler

Spouse/Ex: Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole (m. 1836)

Early Life

Mary Seacole, a Jamaican nurse who cared for British soldiers at the battlefront during the Crimean War, was born on November 23, 1805, in Kingston, Jamaica. She described this as “a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers”, and provided succour for wounded servicemen on the battlefield. She was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1991. Her father was a Scottish soldier and her mother a free black Jamaican woman who was skilled in traditional medicine. In 2004 she was voted the greatest black Briton.

Seacole was a mixed-race nurse who cared for British soldiers at the battlefront during the Crimean War by setting up a “British Hotel” where she provided assistance and relief to servicemen wounded on the battlefield. Born as the daughter of a Scottish soldier in the British Army and a free Jamaican woman, Mary acquired knowledge of herbal medicines from her mother who was skilled in traditional medicines. She also inherited her mother’s compassion and started helping her in caring for invalids at their boarding house while she was still a young girl. She grew up to be an independent-minded woman and traveled independently to several places, including London.

When the Crimean War broke out, Seacole was one of two outstanding nurses to tend to the wounded, along with Florence Nightingale. Seacole applied to the War Office to assist but was refused, so she traveled independently and set up her hotel and assisted battlefield wounded. She became extremely popular among service personnel, who raised money for her when she faced destitution after the war.

Deciding to take things into her own hands, she traveled on her own to the Crimea where she established the British Hotel to provide food, medicines and other necessities to the soldiers. She returned to England after the end of the war and was hailed as a heroine for her role in easing the sufferings of the wounded and ailing soldiers.

She operated several successful businesses in the Caribbean and Latin America but was best known for her talents as an herbal medicine specialist. Her service during the Crimean conflict endeared her to hundreds of British soldiers she treated. “I do not pray to God that I may never see its like again, for I wish to be useful all my life,” Seacole wrote of the horrors of that war in her autobiography.

After her death, Mary Seacole was largely forgotten for almost a century but today is celebrated as a woman who made a success of her career, despite experiencing racial prejudice. Her autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (1857), is one of the earliest autobiographies of a mixed-race woman, although some aspects of its accuracy have been questioned by present-day supporters of Nightingale. The erection of a statue of her at St Thomas’ Hospital, London on 30 June 2016, describing her as a “pioneer nurse”, has generated controversy and opposition from supporters of Nightingale. Earlier controversy broke out in the United Kingdom late in 2012 over reports of a proposal to remove her from the UK’s National Curriculum.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Mary Seacole, née Mary Jane Grant, was born on 23 November 1805 in Kingston, Jamaica. Her father was a Scottish soldier in the British Army while her mother was a free Jamaican woman. Mary was proud of her multiracial heritage. Her mother was a “doctress”, a healer who used the traditional Caribbean and African herbal remedies, who ran Blundell Hall, a boarding house at 7 East Street, considered one of the best hotels in all of Kingston. Here Seacole acquired her nursing skills. Seacole’s autobiography says she began experimenting in medicine, based on what she learned from her mother, by ministering to a doll and then progressing to pets before helping her mother treat humans.

At the time of Seacole’s birth, Jamaica was emerging as the world’s leading exporter of sugar, which was shipped out of the bustling port city of Kingston to the rest of the vast British Empire and its assorted trading partners. Blacks were not native to Jamaica but brought in by the British from Africa to serve as free labor on sugar plantations. In 1800, just five years before she was born, the island’s 300,000 slaves outnumbered the white population 10 to 1.

As a girl, Mary spent some years in the house of an elderly woman. Described as a “kind patroness” by Mary, the elderly lady treated her like a family member and ensured that she received a good education. She grew up to be an intelligent and independent-minded young woman. She traveled a lot as a youth and visited other parts of the Caribbean, including Cuba, Haiti and the Bahamas.

Mary Seacole spent some years in the household of an elderly woman, whom she called her “kind patroness”, before returning to her mother. She was treated as a member of her patroness’s family and received a good education. As the educated daughter of a Scottish officer and a free black woman with a respectable business, Seacole would have held a high position in Jamaican society.

She went to London in 1821 and stayed there for a year. There she acquired knowledge about modern European medicine which supplemented her training in traditional Caribbean medicine. She made several trips to Jamaica and back over the next few years before returning to Jamaica in 1825.

Personal Life

Mary Seacole married Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston on 10 November 1836. Her marriage, from betrothal to widowhood, is described in just nine lines at the conclusion of the first chapter of her autobiography. The newly married couple moved to Black River and opened a provisions store which failed to prosper. They returned to Blundell Hall in the early 1840s.

After her husband’s death in 1844, she gained further nursing experience during a cholera epidemic in Panama, and, after returning to Jamaica, she cared for yellow fever victims, many of whom were British soldiers. She never remarried even though she received several marriage proposals as a widow.

Career and Works

Mary Seacole took care of her elderly patroness back home and nursed her till her death. Then she joined her mother in her work and occasionally assisted others at the British Army hospital at Up-Park Camp. Her mother died during the mid-1840s and Mary was plunged into grief at the loss of her beloved mother. By this time she had also been married and widowed. With great courage, she composed herself and took over the management of her mother’s hotel.

In her autobiography, Seacole makes almost no mention of political events that shaped Jamaica, including numerous slave uprisings and the eventual abolition of slavery in 1834. Fiercely committed to the notion of Empire, and proud to be a British subject, she had longed to visit London since her girlhood, and finally made her first trip there around 1821. As a single woman, she had to have a male accompany her, and wrote in her autobiography that her companion’s skin was darker than hers and they were sometimes taunted by children on the street, for blacks were still a rarity anywhere in Europe. She made another trip to London about a year later, this time bringing with her a large cache of West Indian spices and her own homemade jams to sell, and stayed until around 1825. In her autobiography, Seacole was vague about many details of her life and exact whereabouts, and therefore how she may have earned a living at times has been the subject of conjecture. She did visit the Bahamas, Haiti, and Cuba, probably selling her jams and spices, and helped her mother at the boarding house back in Kingston.

During 1843 and 1844, Seacole suffered a series of personal disasters. She and her family lost much of the boarding house in a fire in Kingston on 29 August 1843. Blundell Hall burned down, and was replaced by New Blundell Hall, which was described as “better than before”. Then her husband died in October 1844, followed by her mother. After a period of grief, in which Seacole says she did not stir for days, she composed herself, “turned a bold front to fortune”, and assumed the management of her mother’s hotel. She put her rapid recovery down to her hot Creole blood, blunting the “sharp edge of her grief” sooner than Europeans who she thought “nurse their woe secretly in their hearts”. She absorbed herself in work, declining many offers of marriage. She later became widely known and respected, particularly among the European military visitors to Jamaica who often stayed at Blundell Hall. She treated patients in the cholera epidemic of 1850, which killed some 32,000 Jamaicans. Seacole attributed the outbreak to infection brought on a steamer from New Orleans, Louisiana, demonstrating knowledge of contagion theory. This first-hand experience would benefit her during the next five years.

Mary became absorbed in her work and gained a reputation as a widely respected nurse over the next few years. A cholera epidemic struck Jamaica in 1850 in which thousands of people lost their lives. It marked a very stressful and hectic period in Mary Seacole’s life though she served her patients with undying commitment.

In 1850 Seacole joined her half-brother in Panama, which was receiving a steady influx of travelers on their way to the California gold rush. On the Panamanian isthmus, she had a provisions business that sold supplies to the travelers but continued to run a boarding house and serve clients as a doctress, as female herbal medicinists were called at the time. Her reputation grew after she treated many cholera victims during one outbreak with a remedy that involved giving the patient large amounts of water in which cinnamon had been boiled. Cholera was a bacterial disease most commonly caused by drinking contaminated water, and cinnamon’s essential oil has antimicrobial properties. She also became particularly adept at treating victims of violence in the rough-and-tumble Spanish garrison towns of the isthmus, where fights and knife wounds were common. By 1852 she had returned to Jamaica, where she established a makeshift military hospital for British soldiers sickened by another yellow fever epidemic on the island.

In 1851, she went to Cruces in Panama to visit her brother who lived there. Shortly after her arrival, the city was swept by an epidemic of cholera. The first patient Seacole treated survived which established her reputation as a knowledgeable medical professional. She received payment from the rich but chose to treat the poor for free.

In 1853, soon after arriving home, Seacole was asked by the Jamaican medical authorities to minister to victims of a severe outbreak of yellow fever. She found that she could do little because the epidemic was so severe. Her memoirs state that her own boarding house was full of sufferers and she saw many of them die. Although she wrote, “I was sent for by the medical authorities to provide nurses for the sick at Up-Park Camp,” she did not claim to bring nurses with her when she went. She left her sister with some nurses at her house, went to the camp (about a mile, or 1.6 km, from Kingston), “and did my best, but it was little we could do to mitigate the severity of the epidemic.”

Seacole was in Panama in 1854 when she learned of the escalating Crimean War which had broken out in October 1853 between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the United Kingdom, France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. She decided to volunteer as a war nurse and traveled to England where she approached the War Office, asking to be sent as an army nurse to the Crimea. Her offer, however, was rejected in spite of her ample experiences.

Seacole was in London in 1854 when reports of the lack of necessities and breakdown of nursing care for soldiers in the Crimean War began to be made public. Despite her experience, her offers to be sent to the front to help were refused, and she attributed her rejection to racial prejudice. In 1855, with the help of a relative of her husband, she went to Crimea as a sutler, setting up the British Hotel to sell food, supplies, and medicines to the troops. She assisted the wounded at the military hospitals and was a familiar figure at the transfer points for casualties from the front. Her remedies for cholera and dysentery were particularly valued. At the war’s end, she returned to England destitute and was declared bankrupt.

When Seacole learned about Britain’s involvement in a faraway conflict known as the Crimean War (1853–56), and the need for nurses to tend the wounded, she decided to volunteer her services. Most of the battles took place on the Crimean peninsula, which later became part of Ukraine. There, British troops had joined their French counterparts to help Turkey push back Russian forces for control of the area, and when reports reached England about how terribly the invalid soldiers had suffered during the first winter, a wealthy British woman who had already made nursing her career began a public awareness campaign to recruit and train women to serve as army nurses. That woman was Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), and her services during the Crimean War made her one of the most famous women in the world.

The Crimean War lasted from October 1853 until 1 April 1856 and was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the United Kingdom, France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. The majority of the conflict took place on the Crimean peninsula in the Black Sea and Turkey.

Nightingale was already in Turkey by the time Seacole arrived in London to offer her services. The doctress, well-known in the Caribbean world, brought with her several letters of reference from British officers in Kingston attesting to her medical skills, compassion, and selflessness, but Nightingale’s recruiter was the wife of a cabinet minister who informed her that all nursing positions had already been filled. “I read in her face the fact that had there been a vacancy I should not have been chosen to fill it,” Seacole wrote, according to a Times of London report published on the centenary of the war in the same newspaper. She and her business partner, Thomas Day the superintendent of the Panama mining camp decided to go anyway, using their own funds. They arrived in Constantinople, Turkey’s main city, where Seacole located Nightingale, who again turned down her request to join the official army nurses’ corps.

Determined in her resolve to serve the soldiers of the war, Mary traveled to Crimea using her own resources and opened the British Hotel. Along with managing the hotel, she also assisted the wounded at the military hospitals. Her experiences of treating cholera patients proved to be extremely valuable during the war. She also operated as a sutler and sold provisions near the British camp even as she attended to the causalities there. She became a much respected and beloved figure due to her services to the soldiers and was widely known to the British Army as “Mother Seacole”.

After the war ended, Seacole returned to London, where a business venture with Day seemed to have gone badly under Day’s mismanagement, and she was forced to declare bankruptcy. Notice of the bankruptcy hearing appeared in the Times in November of 1856, and this elicited a groundswell of sympathy for her from the officers and soldiers she had tended. Her plight came to the attention of Lord Rokeby, a division commander from the war, who urged that a fund is set up to help her. The magazine Punch joined in, printing a poem titled “A Stir for Seacole” and providing an address for donations. The efforts culminated in the Grand Military Festival, held in Seacole’s honor, at the Royal Surrey Gardens in July of 1857. The benefit was the work of Rokeby and another lord, George Paget (1818–1880), who had also been impressed by Seacole’s dedication to his troops.

Seacole arrived in August 1856 and opened a canteen with Day at Aldershot, but the venture failed through lack of funds. She attended a celebratory dinner for 2,000 soldiers at Royal Surrey Gardens in Kennington on 25th August 1856, at which Nightingale was the chief guest of honor. Reports in The Times on 26th August and News of the World on 31st August indicate that Seacole was also fêted by the huge crowds, with two “burly” sergeants protecting her from the pressure of the crowd. However, creditors who had supplied her firm in Crimea were in pursuit. She was forced to move to 1, Tavistock Street, Covent Garden in increasingly dire financial straits. The Bankruptcy Court in Basinghall Street declared her bankrupt on 7th November 1856. Robinson speculates that Seacole’s business problems may have been caused in part by her partner, Day, who dabbled in horse trading and may have set up as an unofficial bank, cashing debts.

In 1857 her autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, was published and became a best-seller. A festival was held in her honor to raise funds and acknowledge her contributions, and she received decorations from France, England, and Turkey. Seacole’s memoir, the first autobiography written by a black woman published in Britain, became a bestseller, but she returned to Jamaica in 1859, somewhat dejected for failing to have won an audience with Her Majesty, Queen Victoria (1819–1901). Race did not seem to be a factor, for the queen had been known to meet with and even financially assist subjects of the Empire who were of African or Asian heritage. Seacole’s biographers speculate that Florence Nightingale who became close to the monarch in the years following her Crimean War fame had spread rumors that Seacole ran a brothel, and seemed to have known that Seacole had given birth to a daughter out of wedlock, whom she brought to Crimea but never mentioned in her autobiography.

In May 1857 Mary wanted to travel to India, to minister to the wounded of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but she was dissuaded by both the new Secretary of War, Lord Panmure, and her financial troubles. Fund-raising activities included the “Seacole Fund Grand Military Festival”, which was held at the Royal Surrey Gardens, from Monday 27 July to Thursday 30 July 1857. This successful event was supported by many military men, including Major General Lord Rokeby (who had commanded the 1st Division in Crimea) and Lord George Paget; over 1,000 artists performed, including 11 military bands and an orchestra conducted by Louis Antoine Jullien, which was attended by a crowd of circa 40,000. The one-shilling entrance charge was quintupled for the first night and halved for the Tuesday performance. However, production costs had been high and the Royal Surrey Gardens Company was itself having financial problems. It became insolvent immediately after the festival, and as a result of Seacole only received £57, one-quarter of the profits from the event. When eventually the financial affairs of the ruined Company were resolved, in March 1858, the Indian Mutiny was over.

The British press highlighted her case and a fund was set up to bail her out of her financial troubles. Mary went to Jamaica in 1860 but was back to England in 1870 and spent the rest of her life in London. Returning to London around 1870 as a new conflict, the Franco-Prussian War, raged in Europe, Seacole contacted a member of parliament who was heading British relief services for it an agency that was the forerunner of the Red Cross and offered her help, but the politician was Nightingale’s brother-in-law, and once again her generosity was spurned. For a time she served as a masseuse to Alexandra, the Princess of Wales, who suffered from painful rheumatism.

Awards and Honor

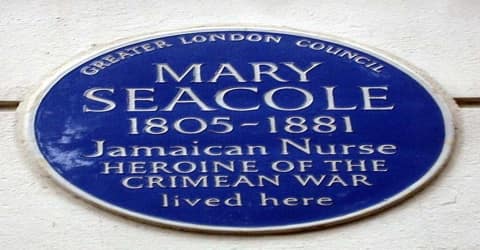

(Plaque commemorating Mary Seacole at 14 Soho Square, London W1)

Mary Seacole was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1991.

The centenary of her death was celebrated with a memorial service on 14 May 1981 and the grave is maintained by the Mary Seacole Memorial Association, an organization founded in 1980 by Jamaican-British Auxiliary Territorial Service corporal, Connie Mark.

She was voted the greatest black Briton in 2004.

A “green plaque” was unveiled at 147 George Street, in Westminster, on 11 October 2005. However, another blue plaque has since been positioned at 14 Soho Square, where she lived in 1857.

Death and Legacy

Mary Seacole died on May 14, 1881, at her home in Paddington, London, with the cause of death listed as apoplexy, or a stroke. She was buried in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, Harrow Road, Kensal Green, London. She left an estate valued at over £2,500. After some specific legacies, many of exactly 19 guineas, the main beneficiary of her will was her sister, (Eliza), Louisa. Lord Rokeby, Colonel Hussey Fane Keane, and Count Gleichen (three trustees of her Fund) were each left £50; Count Gleichen also received a diamond ring, said to have been given to Seacole’s late husband by Lord Nelson. A short obituary was published in The Times on 21 May 1881.

Seacole is best remembered as the nurse who set up a “British Hotel” all by herself during the Crimean War to care for the sick and wounded soldiers. She provided food, medicines and other supplies to the injured and convalescent servicemen and served them selflessly. So dedicated was she in her service that she lost her own good health and much of her money by the end of the war.

Her grave in London was rediscovered in 1973; service of reconsecration was held on 20 November 1973, and her impressive gravestone was also restored by the British Commonwealth Nurses’ War Memorial Fund and the Lignum Vitae Club. Nonetheless, when scholarly and popular works were written in the 1970s about the Black British presence, she was absent from the historical record and went unrecorded by Edward Scobie and Sebastian Okechukwu Mezu.

After her death, she fell into obscurity but in 2004 took first place in the 100 Great Black Britons poll in the United Kingdom. In January of 2005, a previously unknown portrait of Seacole was permanently installed at the National Portrait Gallery of Britain.

By the 21st century, Mary Seacole was much more prominent. Several buildings and entities, mainly connected with health care, were named after her. In 2005, British politician Boris Johnson wrote of learning about Seacole from his daughter’s school pageant and speculated: “I find myself facing the grim possibility that it was my own education that was blinkered.” In 2007 Seacole was introduced into the National Curriculum, and her life story is taught at many primary schools in the UK alongside that of Florence Nightingale.

Information Source: