Biography of Siegfried Sassoon

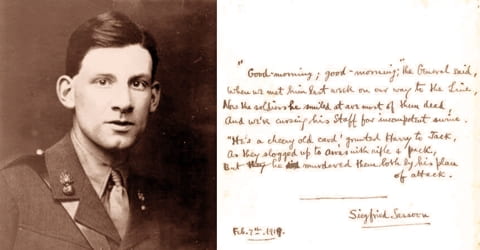

Siegfried Sassoon – English poet, writer, and soldier.

Name: Siegfried Loraine Sassoon

Penname: Saul Kain, Pinchbeck Lyre

Date of Birth: 8 September 1886

Place of Birth: Matfield, Kent, England

Date of Death: 1 September 1967 (aged 80)

Place of Death: Heytesbury, Wiltshire, England

Occupation: Soldier, poet, diarist, memoirist, journalist

Father: Alfred Ezra Sassoon (1861–1895)

Mother: Theresa

Spouse: Hester Gatty (m. 1933–1945)

Children: George Sassoon

Early Life

Siegfried Sassoon (a famous historian, poet, writer, and soldier) was born September 8, 1886, Brenchley, Kent, England. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches and satirized the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon’s view, were responsible for a jingoism-fuelled war.

In an era where people were lured by patriotic propaganda and romantic, heroic ideas of war, his poetry conveyed the merciless, inhumane and cold-blooded actualities on the war front. The trademark of all his writings is the details of foul-smelling rotting corpses, distorted limbs, filth, suicide, and blood, which served as an effective anti-war stance. This type of writing had a significant impact on the genre of modernist poetry.

Sassoon became a focal point for dissent within the armed forces when he made a lone protest against the continuation of the war in his “Soldier’s Declaration” of 1917, culminating in his admission to a military psychiatric hospital; this resulted in his forming a friendship with Wilfred Owen, who was greatly influenced by him. Sassoon later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalized autobiography, collectively known as the “Sherston trilogy”.

Unlike many of the poets who had memorialized the great achievements of the British Empire in their war poetry, Sassoon addressed the human dimension, the cost of war to the combatants in both physical and more profound, psychological torment. In poems such as “Suicide in the Trenches,” Sassoon presents the anguish of combat from the soldier’s perspective. The “War to End All Wars” was a gruesome affair, and the sense of the glory of war was replaced by a growing sense of despair, as many thousands of combatants gave their lives for, literally, a few square yards of territory. The sense of optimism of the Progressive era disappeared, giving way to a general malaise.

Some of his well-known poems include, ‘The Old Huntsman’, The Hero’, ‘Aftermath’, ‘I Stood with the Dead’, ‘Trench Duty’ and ‘Repression of War’. Disillusioned with war, he refused to return to duty and strongly condemned it. As the witness to great bloodshed, he wrote a series of semi-autobiographical books viz., ‘Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man’, ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer’ and ‘Sherston’s Progress’. This series of books came to be known as the ‘Sherston trilogy’.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon was born on September 8, 1886, Brenchley, Kent, England, to a Jewish father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon, who was a descendant of a wealthy merchant family from Baghdad and Theresa, an Anglo-Catholic mother. His father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon (1861–1895), son of Sassoon David Sassoon, was a member of the wealthy Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon merchant family. His mother, Theresa, belonged to the Thornycroft family, sculptors responsible for many of the best-known statues in London her brother was Sir Hamo Thornycroft. There was no German ancestry in Sassoon’s family; he owed his unusual first name to his mother’s predilection for the operas of Wagner. His middle name was taken from the surname of a clergyman with whom she was friendly.

He was educated at The New Beacon Preparatory School, Sevenoaks, Kent and majored in history at Clare College, Cambridge from 1905-1907.

However, he dropped out of university without a degree and spent the next few years hunting, playing cricket, and privately publishing a few volumes of not very highly acclaimed poetry. His income was just enough to prevent his having to seek work, but not enough to live extravagantly. His first real success was The Daffodil Murderer, a parody of The Everlasting Mercy by John Masefield, published in 1913, under the pseudonym of “Saul Kain.”

Personal Life

Sassoon wanted to play for Kent County Cricket Club; Kent Captain Frank Marchant was a neighbor of Sassoon. Siegfried often turned out for Blue houses at the Nevill Ground, Tunbridge Wells, where he sometimes played alongside Arthur Conan Doyle. He had also played cricket for his house at Marlborough College, once taking 7 wickets for 18 runs. Although an enthusiast, Sassoon was not good enough to play for Kent, he played cricket for Matfield village, and later for the Downside Abbey team, continuing into his seventies.

Sassoon was romantically involved with men including, William Park, ‘Gabriel’ Atkin, actor Ivor Novello; Novello’s former lover, Glen Byam Shaw; German aristocrat, Prince Philipp of Hesse; the writer Beverley Nichols; an effete aristocrat, the Hon. Stephen Tennant.

In December 1933, to many people’s surprise, Sassoon married Hester Gatty, who was many years his junior; this led to the birth of a child, something which he had long craved. This child, their only child, George (1936-2006), became a noted scientist, linguist, and author, and was adored by Siegfried, who wrote several poems addressed to him. However, the marriage broke down after World War II, Sassoon apparently unable to find a compromise between the solitude he enjoyed and the companionship he craved.

Separated from his wife in 1945, Sassoon lived in seclusion at Heytesbury in Wiltshire, although he maintained contact with a circle which included E M Forster and J R Ackerley. One of his closest friends was the cricketer, Dennis Silk who later became Warden (headmaster) of Radley College. He also formed a close friendship with Vivien Hancock, then headmistress of Greenways School at Ashton Gifford, where his son George was a pupil. The relationship provoked Hester to make strong accusations against Hancock, who responded with the threat of legal action.

Siegfried Sassoon’s only child, George Sassoon, died of cancer in 2006. George had three children, two of whom were killed in a car crash in 1996.

Towards the end of his life, Sassoon converted to Roman Catholicism. He had hoped that Ronald Knox, a Roman Catholic priest, and writer whom he admired, would instruct him in the faith, but Knox was too ill to do so. The priest Sebastian Moore was chosen to instruct him instead, and Sassoon was admitted to the faith at Downside Abbey in Somerset. He also paid regular visits to the nuns at Stanbrook Abbey, and the Abbey press printed commemorative editions of some of his poems. During this time he also became interested in the supernatural and joined the Ghost Club.

Career and Works

Sassoon’s first published success, The Daffodil Murderer (1913), was a parody of John Masefield’s The Everlasting Mercy. Robert Graves, in Good-Bye to All that describes it as a “parody of Masefield which, midway through, had forgotten to be a parody and turned into rather good Masefield.”

He joined the British Army just before the onset of World War I and joined the ‘Sussex Yeomanry’, a regiment of the British Army, on August 4, 1914. It also happened to be the day the United Kingdom declared war.

Sassoon enlisted in World War I and was twice wounded seriously while serving as an officer in France. It was his antiwar poetry, such as The Old Huntsman (1917) and Counterattack (1918), and his public affirmation of pacifism, after he had won the Military Cross and was still in the army, that made him widely known. His antiwar protests were at first attributed to shell shock, and he was confined for a time in a sanatorium, where he met and influenced another pacifist soldier-poet, Wilfred Owen, whose works he published after Owen was killed at the front.

Sassoon broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing. (Rupert Brooke, whom Sassoon had briefly met, died in April on the way to Gallipoli.) He was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion (Special Reserve), Royal Welch Fusiliers, as a second lieutenant on 29 May 1915. On 1 November his younger brother Hamo was killed in the Gallipoli Campaign, and in the same month, Siegfried was sent to the 1st Battalion in France. There he met Robert Graves, and they became close friends. United by their poetic vocation, they often read and discussed each other’s work.

He soon became horrified by the realities of war, and the tone of his writing changed completely. His early poems exhibit a Romantic dilettantish sweetness, but his war poetry moves to an increasingly discordant music, intended to convey the ugly truths of the trenches to an audience hitherto lulled by patriotic propaganda. Details such as rotting corpses, mangled limbs, filth, cowardice, and suicide are all trademarks of his work at this time, and this philosophy of “no truth unfitting” had a significant effect on the movement towards Modernist poetry.

While he was on duty in the Western Front he discovered a German trench with 60 odd German soldiers in it; armed with only grenades he captured the trench. He was highly appreciated for his bravery. Stuck by the grief of the sudden death of a close friend at war, he wanted to campaign against the war and in 1917, he finally decided to take a stand against the conduct of the war.

In August 1916, Sassoon arrived at Somerville College, Oxford, which was used as a hospital for convalescing officers, with a case of gastric fever. He wrote: To be lying in a little white-walled room, looking through the window on to a College lawn, was for the first few days very much like a paradise. Graves ended up at Somerville as well. How unlike you to crib my idea of going to the Ladies’ College at Oxford, Sassoon wrote to him in 1917.

At the end of a period of convalescent leave, Sassoon declined to return to duty; instead, encouraged by pacifist friends such as Bertrand Russell and Lady Ottoline Morrell, he sent a letter to his commanding officer titled “A Soldier’s Declaration,” which was forwarded to the press and read out in Parliament by a sympathetic Member of Parliament. Rather than court-martial Sassoon, the military authorities decided that he was unfit for service and sent him to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, where he was officially treated for neurasthenia (“shell shock”).

In 1918, he was wounded while on duty, when a fellow soldier accidentally mistook him to be a German and shot him in the head. After being discharged from the military services he assumed the position of literary editor at the Daily Herald, a British daily newspaper, in 1919.

At Craiglockhart, Sassoon met Wilfred Owen, another poet who would eventually exceed him in fame. It was thanks to Sassoon that Owen persevered in his ambition to write better poetry. A manuscript copy of Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth containing Sassoon’s handwritten amendments survives as testimony to the extent of his influence. Sassoon became to Owen “Keats and Christ and Elijah;” surviving documents demonstrate clearly the depth of Owen’s love and admiration for him. Both men returned to active service in France, but Owen was killed in 1918. Sassoon, having spent some time out of danger in Palestine, eventually returned to the Front and was almost immediately wounded again by friendly fire, but this time in the head and spent the remainder of the war in Britain. After the war, Sassoon was instrumental in bringing Owen’s work to the attention of a wider audience. Their friendship is the subject of Stephen MacDonald’s play, Not About Heroes.

On 13 July 1918, Sassoon was almost immediately wounded again by friendly fire when he was shot in the head by a fellow British soldier who had mistaken him for a German near Arras, France. As a result, he spent the remainder of the war in Britain. By this time he had been promoted to acting captain. He relinquished his commission on health grounds on 12 March 1919 but was allowed to retain the rank of captain.

The novel Regeneration, by Pat Barker, is a fictionalized account of this period in Sassoon’s life and was made into a film starring Jonathan Pryce as W.H.R. Rivers, the psychiatrist responsible for Sassoon’s treatment. Rivers became a kind of surrogate father to the troubled young man, and his sudden death, in 1922, was a major blow to Sassoon.

Having lived for a period at Oxford, where he spent more time visiting literary friends than studying, he dabbled briefly in the politics of the Labour movement, and in 1919 took up a post as literary editor of the socialist Daily Herald. He lived at 54 Tufton Street, Westminster from 1919 to 1925; the house is no longer standing, but the location of his former home is marked by a memorial plaque.

During his period at the Herald, Sassoon was responsible for employing several eminent names as reviewers, including E. M. Forster and Charlotte Mew, and commissioned original material from “names” like Arnold Bennett and Osbert Sitwell. His artistic interests extended to music. While at Oxford he was introduced to the young William Walton, to whom he became a friend and patron. Walton later dedicated his Portsmouth Point overture to Sassoon in recognition of his financial assistance and moral support.

Sassoon was a great admirer of the Welsh poet, Henry Vaughan. On a visit to Wales in 1923, he paid a pilgrimage to Vaughan’s grave at Llansanffraid, Powys, and there wrote one of his best-known peacetime poems, At the Grave of Henry Vaughan. The deaths of three of his closest friends, Edmund Gosse, Thomas Hardy, and Frankie Schuster (the publisher), within a short space of time, came as another serious setback to his personal happiness. At the same time, Sassoon was preparing to take a new direction. While in America, he had experimented with a novel. In 1928, he branched out into prose, with Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, the anonymously-published first volume of a fictionalized autobiography, which was almost immediately accepted as a classic, bringing its author new fame as a humorous writer. The book won the 1928 James Tait Black Award for fiction.

In 1928, he authored the first semi-autobiographical novel ‘Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man’, which is regarded as a classic in English literature. In 1930, his second semi-autobiographical novel titled, ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer’ was published which narrates a semi-fictional account of his life during and post-World War.

In 1936, the final book of his semi-autobiographical trilogy, ‘Sherston’s Progress’ was published.

In later years, he revisited his youth and early manhood with three volumes of genuine autobiography, which were also widely acclaimed. These were The Old Century, The Weald of Youth and Siegfried’s Journey.

Awards and Honor

(Blue plaque, 23 Campden Hill Square, London)

On July 27, 1916, Sassoon was awarded the Military Cross, an award granted in recognition of active operations against the enemy on land.

In 1951, he was appointed as the Commander of the Order of the British Empire, an official honor awarded as part of the New Year Honours in Commonwealth Realms.

Death and Legacy

(Siegfried Sassoon’s gravestone in Mells churchyard)

Sassoon died from stomach cancer on 1 September 1967, one week before his 81st birthday. He is buried at St Andrew’s Church, Mells, Somerset, not far from the grave of Father Ronald Knox whom he so admired. He is one among the sixteen ‘Great War poets’ honored on a slate stone which was unveiled at the Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner.

The inscription on the stone was written by friend and fellow War poet Wilfred Owen. It reads: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.

Sassoon’s long-lost Military Cross turned up in a relative’s attic in May 2007. Subsequently, the medal was put up for sale by his family. It was bought by the Royal Welch Fusiliers for display at their museum in Caernarfon.

Sassoon’s other service medals went unclaimed until 1985 when his son George obtained them from the Army Medal Office, then based at Droitwich. The “late claim” medals consisting of the 1914-15 Star, Victory Medal, and British War Medal along with Sassoon’s CBE and Warrant of Appointment were auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2008.

Several of Sassoon’s poems have been set to music, some during his lifetime, notably by Cyril Rootham, who co-operated with the author.

The novel Regeneration, by Pat Barker, is a fictionalized account of this period in Sassoon’s life and was made into a film starring James Wilby as Sassoon and Jonathan Pryce as W. H. R. Rivers, the psychiatrist responsible for Sassoon’s treatment. Rivers became a kind of surrogate father to the troubled young man, and his sudden death in 1922 was a major blow to Sassoon.

Information Source: