Biography of Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch – Norwegian Painter.

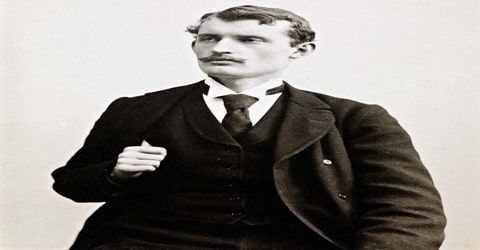

Name: Edvard Munch

Date of Birth: 12 December 1863

Place of Birth: Ådalsbruk, Løten, United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

Date of Death: 23 January 1944 (aged 80)

Place of Death: Oslo, Norway

Occupation: Painter

Father: Christian Munch

Mother: Laura Catherine Bjølstad

Early Life

The Norwegian painter and graphic artist Edvard Munch was born on 12 December 1863, in a farmhouse in the village of Ådalsbruk in Løten, United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, to Laura Catherine Bjølstad and Christian Munch, the son of a priest. His childhood was overshadowed by illness, bereavement and the dread of inheriting a mental condition that ran in the family. Studying at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania (today’s Oslo), Munch began to live the bohemian life, under the largely negative influence of the nihilist Hans Jæger, who did, however, urge him to paint his own emotional and psychological state (‘soul painting’). From this would presently emerge his distinctive style.

Edvard developed a free-flowing style of painting which though built upon the principles of the late 19th century Symbolism, was unique in its own right. What distinguished his paintings from those of others was the profound psychological themes that underlined his works. He often drew inspiration from morbid topics like illness, depression, and death probably a result of the tragedies and losses he suffered during his childhood. His mother died when he was just five and he also lost an elder sister when he was a kid. His other siblings too did not enjoy good health, adding to his woes. His father was a caring person, and he grew up in a culturally stimulating home, but the early unhappy memories of his losses always haunted him.

As his fame and wealth grew, his emotional state remained as insecure as ever. He briefly considered marriage, but could not commit himself. A breakdown in 1908 forced him to give up heavy drinking, and he was cheered by his increasing acceptance by the people of Kristiania and exposure in the city’s museums. His later years were spent working in peace and privacy. Although his works were banned in Nazi Germany, most of them survived World War II, ensuring him a secure legacy.

Edvard was a Norwegian painter and printmaker whose intensely evocative treatment of psychological themes built upon some of the main tenets of late 19th-century Symbolism and greatly influenced German Expressionism in the early 20th century. His painting The Scream, or The Cry (1893), can be seen as a symbol of modern spiritual anguish. His art was a major influence of the expressionist movement, in which where artists sought to give rise to emotional responses.

Naturally talented, Edvard poured out his grief onto the canvas, in the form of intense paintings with deep underlying psychological themes. Eventually, he became a much-respected artist, recognized all over the world for his invaluable contributions to the Expressionist movement.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Edvard Munch was born on 12 December 1863 in a farmhouse in the village of Adalsbruk in Norway. His father Christian Munch was a doctor and medical officer, who was also very religious. His mother Laura Catherine was 20 years younger than his father. He had one elder sister and three younger siblings.

Childhood experiences with death and sickness both his mother and sister died of tuberculosis (an often-fatal disease that attacks the lungs and bones) greatly influenced his emotional and intellectual development. This and his father’s fanatic Christianity led Munch to view his life as dominated by the “twin black angels of insanity and disease.”

Munch eventually captured the latter event in his first masterpiece, The Sick Child (1885–86). Munch’s father and brother also died when he was still young, and another sister developed mental illness. “Illness, insanity, and death,” as he said, “were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle and accompanied me all my life.”

Edvard Munch enrolled in a technical college in 1879 to study engineering. But his heart was not in engineering in spite of the fact that he excelled in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. He realized that his true calling was to be a painter and thus he quit his studies. He enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design of Christiania in 1881. There he received training from instructors such as the sculptor Julius Middelthun and the naturalistic painter Christian Krohg.

Munch’s paintings during the 1880s were dominated by his desire to use the artistic vocabulary of realism to create subjective content, or content open to interpretation of the viewer. His Sick Child (1885–1886), which used a motif (dominant theme) popular among Norwegian realist artists, created through color a mood of depression that served as a memorial to his dead sister. Because of universal critical rejection, Munch turned briefly to a more mainstream style, and through the large painting Spring (1889), a more academic version of the Sick Child, he obtained state support for study in France.

Personal Life

In 1899, Edvard Munch began an intimate relationship with Tulla Larsen, a “liberated” upper-class woman. They traveled to Italy together and upon returning, Munch began another fertile period in his art, which included landscapes and his final painting in “The Frieze of Life” series, The Dance of Life (1899). Larsen was eager for marriage, and Munch begged off. His drinking and poor health reinforced his fears, as he wrote in the third person: “Ever since he was a child he had hated marriage. His sick and nervous home had given him the feeling that he had no right to get married.” Munch almost gave in to Tulla, but fled from her in 1900, also turning away from her considerable fortune, and moved to Berlin.

In late 1908 Munch entered the clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson for therapy to deal with his mental issues. The treatment helped him and he returned to painting in 1909. Once again he was able to establish his reputation.

Career and Works

Edvard Munch was a Norwegian painter whose work was highly influential to German Expressionism in both style and theme. German Expressionism is an early twentieth-century movement in art, a cultural exemplar of abstract expressionism. Art historians usually characterize German Expressionism as an art movement inextricable from the cultural zeitgeist, or spirit of the times. German Expressionism refers to a cultural movement with many different manifestations. In the film, for example, the style presents with Gothic imagery and high contrast black-or-white compositions. In painting, it manifests in an artistic style that features emotional overtones coupled with a subjective way of seeing.

In 1883, Munch took part in his first public exhibition and shared a studio with other students. His full-length portrait of Karl Jensen-Hjell, a notorious bohemian-about-town, earned a critic’s dismissive response: “It is impressionism carried to the extreme. It is a travesty of art.” Munch’s nude paintings from this period survive only in sketches, except for Standing Nude (1887). They may have been confiscated by his father. He experimented with many styles during the early years of his career. He dabbled in Naturalism and Impressionism and painted several portraits and nudes. He completed his painting ‘The Sick Child’ in 1886, symbolically representing his emotions at the time of his sister’s death some years ago.

Munch soon outgrew the prevailing naturalist aesthetic in Kristiania, partly as a result of his assimilation of French Impressionism after a trip to Paris in 1889 and his contact from about 1890 with the work of the Post-Impressionist painters Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In some of his paintings from this period, he adopted the Impressionists’ open brushstrokes, but Gauguin’s use of the bounding line was to prove more congenial to him, as was the Synthetist artists’ ambition to go beyond the depiction of external nature and give form to an inner vision. His friend the Danish poet Emanuel Goldstein introduced him to French Decadent Symbolist poetry during this period, which helped him formulate a new philosophy of art, imbued with a pantheistic conception of sexuality.

The death of his father in 1889 caused a major spiritual crisis, and he soon rejected Jaeger’s philosophy. Munch’s Night in St. Cloud (1890) embodied a renewed interest in spiritual content; this painting served as a memorial to his father by presenting the artist’s dejected state of mind. He summarized his intentions, saying “I paint not what I see, but what I saw,” and identified his paintings as “symbolism: nature viewed through a temperament” (manner of thinking). Both statements accent the transformation of nature as the artist experienced it.

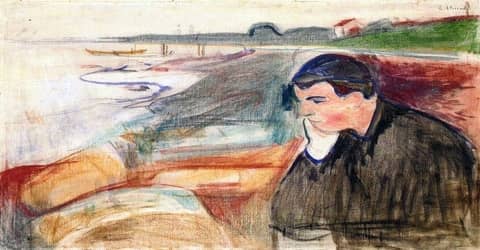

(Melancholy, 1891, oil, pencil and crayon on canvas)

In 1889, Munch traveled to France and lived there for the next three years. During this period he painted a series of paintings called the “Frieze of Life”, which encompassed 22 works for a Berlin exhibition. The collection consisted of paintings such as “Despair”, “Melancholy”, “Anxiety”, “Jealousy”, and most importantly, “The Scream”, which became one of his best-known paintings. This collection proved to be a great success and established him as a popular artist.

Edvard Munch embraced painting as a practice of self-knowledge. He wrote: ‘in my art, I attempt to explain life and its meaning to myself.’ Munch embraced a bohemian lifestyle. He rejected the impressionist style for its aesthetic limitations and identified with the avant-garde experimentalism of expressionists like Paul Klee and August Strindberg.

By 1892, Munch formulated his characteristic, and original, Synthetist aesthetic, as seen in Melancholy (1891), in which color is the symbol-laden element. Considered by the artist and journalist Christian Krohg as the first Symbolist painting by a Norwegian artist, Melancholy was exhibited in 1891 at the Autumn Exhibition in Oslo. In 1892, Adelsteen Normann, on behalf of the Union of Berlin Artists, invited Munch to exhibit at its November exhibition, the society’s first one-man exhibition. However, his paintings evoked bitter controversy (dubbed “The Munch Affair”), and after one week the exhibition closed. Munch was pleased with the “great commotion”, and wrote in a letter: “Never have I had such an amusing time it’s incredible that something as innocent as painting should have created such a stir.”

The outraged incomprehension of his work by Norwegian critics was echoed by their counterparts in Berlin when Munch exhibited a large number of his paintings there in 1892 at the invitation of the Union of Berlin Artists. The violent emotion and unconventional imagery of his paintings, especially their daringly frank representations of sexuality, created a bitter controversy. Critics were also offended by his innovative technique, which to most appeared unfinished. The scandal, however, helped make his name known throughout Germany, and from there, his reputation spread farther. Munch lived mainly in Berlin in 1892–95 and then in Paris in 1896–97, and he continued to move around extensively until he settled in Norway in 1910.

With time he grew extremely famous and his financial situation also improved considerably. However, his personal demons continued to haunt him. He became an alcoholic and his mental problems became more severe. This also began to affect his career as an artist. During his four years in Berlin, Munch sketched out most of the ideas that would comprise his major work, The Frieze of Life, first designed for book illustration but later expressed in paintings. He sold little but made some income from charging entrance fees to view his controversial paintings. Already, Munch was showing a reluctance to part with his paintings, which he termed his “children”.

His other paintings, including casino scenes, show a simplification of form and detail which marked his early mature style. Munch also began to favor a shallow pictorial space and a minimal backdrop for his frontal figures. Since poses were chosen to produce the most convincing images of states of mind and psychological conditions, as in Ashes, the figures impart a monumental, static quality. Munch’s figures appear to play roles on a theatre stage (Death in the Sick-Room), whose pantomime of fixed postures signify various emotions; since each character embodies a single psychological dimension, as in The Scream, Munch’s men and women began to appear more symbolic than realistic. He wrote, “No longer should interiors be painted, people reading and women knitting: there would be living people, breathing and feeling, suffering and loving.”

At the heart of Munch’s achievement is his series of paintings on love and death. Its original nucleus was formed by six pictures exhibited in 1893, and the series had grown to 22 works by the time it was first exhibited under the title Frieze of Life at the Berlin Secession in 1902. Munch constantly rearranged these paintings, and if one had to be sold, he would make another version of it. Thus in many cases, there are several painted versions and prints based on the same image. Although the Frieze draws deeply on personal experience, its themes are universal: it is not about particular men or women but about man and woman in general, and about the human experience of the great elemental forces of nature. Seen in sequence, an implicit narrative emerges of love’s awakening, blossoming, and withering, followed by despair and death.

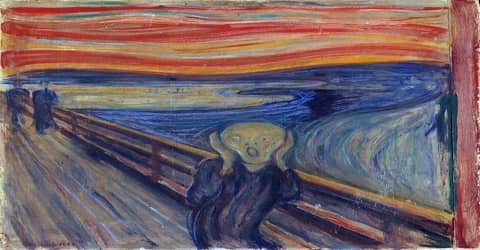

The Scream (1893)

The Scream is Munch’s most famous work, and one of the most recognizable paintings in all art. It has been widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. Painted with broad bands of garish color and highly simplified forms, and employing a high viewpoint, it reduces the agonized figure to a garbed skull in the throes of an emotional crisis. The Scream exists in four versions: two pastels (1893 and 1895) and two paintings (1893 and 1910). There are also several lithographs of The Scream (1895 and later).

Love’s awakening is shown in The Voice (1893), where on a summer night a girl standing among trees seems to be summoned more by an inner voice than by any sounds from a boat on the sea behind her. Compositionally, this is one of several paintings in the Frieze in which the winding horizontal of the coastline is counterpoised with the verticals of trees, figures, or the pillarlike reflection across the sea of sun or moon. Love’s blossoming is shown in The Kiss (1892), in which a man and woman are locked in a tender and passionate embrace, their bodies merging into a single undulating form and their faces melting so completely into each other that neither retains any individual features.

“The Frieze of Life” themes recur throughout Munch’s work but he especially focused on them in the mid-1890s. In sketches, paintings, pastels, and prints, he tapped the depths of his feelings to examine his major motifs: the stages of life, the femme fatale, the hopelessness of love, anxiety, infidelity, jealousy, sexual humiliation, and separation in life and death. These themes are expressed in paintings such as The Sick Child (1885), Love and Pain (retitled Vampire; 1893–94), Ashes (1894), and The Bridge. The latter shows limp figures with featureless or hidden faces, over which loom the threatening shapes of heavy trees and brooding houses. Munch portrayed women either as frail, innocent sufferers (see Puberty and Love and Pain) or as the cause of great longing, jealousy, and despair (see Separation, Jealousy, and Ashes).

To make his work accessible to a larger public, Munch began making prints (works of art that could be easily copied) in 1894. Motifs for his prints were usually derived from his paintings, particularly the Frieze. The Frieze also served as the inspiration for the paintings he made for Max Linde (1904), Max Reinhardt’s Kammerspielhaus (1907), and the Freia Chocolate Factory in Oslo (1922).

An especially powerful image of the surrender, or transcendence, of individuality, is Madonna (1894–95), which shows a naked woman with her head thrown back in ecstasy, her eyes closed, and a red halo-like shape above her flowing black hair. This may be understood as the moment of conception, but there is more than a hint of death in the woman’s beautiful face. In Munch’s art, woman is an “other” with whom the union is desperately desired, yet feared because it threatens the destruction of the creative ego.

During the 1900s, his drinking problem spiraled out of control and he began to suffer from hallucinations. In order to reclaim his life, he underwent therapy for a few months and recovered well. Munch returned to painting and re-established his reputation. Once again his career stabilized and his financial position improved. He eventually moved to a country house in Norway where he spent his later years in solitude. He continued painting up to his death, often depicting his physical ailments in his later works.

The Sick Child (1907)

In 1903–04, Munch exhibited in Paris where the coming Fauvists, famous for their boldly false colors, likely saw his works and might have found inspiration in them. When the Fauves held their own exhibit in 1906, Munch was invited and displayed his works with theirs. During this time, Munch received many commissions for portraits and prints which improved his usually precarious financial condition. In 1906, he painted the screen for an Ibsen play in the small Kammerspiele Theatre located in Berlin’s Deutsches Theater, in which the Frieze of Life was hung. The theatre’s director Max Reinhardt later sold it; it is now in the Berlin Nationalgalerie. After an earlier period of landscapes, in 1907 he turned his attention again to human figures and situations

Following a nervous breakdown, Munch entered a hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1908. In the lithograph (a type of print) series Alpha and Omega, he depicted his love affairs and his relationship with friends and enemies. In 1909 he returned to Norway to lead an isolated life. He sought new artistic motifs in the Norwegian landscape and in the activities of farmers and laborers. A more optimistic view of life briefly replaced his former anxiety, and this new life view attained monumental expression in the murals of the Oslo University Aula (1911–1914).

Among the few exceptions is his haunting Self-Portrait: The Night Wanderer (c. 1930), one of a long series of self-portraits he painted throughout his life. An especially important commission, which marked the belated acceptance of his importance in Norway, was for the Oslo University Murals (1909–16), the centrepiece of which was a vast painting of the sun, flanked by allegorical images. Both landscapes and men at work provided subjects for Munch’s later paintings. Yet it was principally through his work of the 1890s, in which he gave form to mysterious and dangerous psychic forces, that he made such a crucial contribution to modern art.

During World War I (1914–18), when Germany led forces against the forces of much of Europe and the United States, Munch returned to his earlier motifs of love and death. Symbolic paintings and prints appeared side by side with stylized studies of landscapes and nudes during the 1920s. As a major project, never completed, he began to illustrate Henrik Ibsen’s (1828–1906) plays. During his last years, plagued by partial blindness, Munch edited the diaries written in his youth and painted harsh self-portraits and memories of his earlier life.

In 1937 Edvard’s work was included in the Nazi exhibition of “degenerate art.” Upon his death, Munch bequeathed his estate and all the paintings, prints, and drawings in his possession to the city of Oslo, which erected the Munch Museum in 1963. Many of his finest works are in the National Gallery in Oslo.

In 1940, the Germans invaded Norway and the Nazi party took over the government. Munch was 76 years old. With nearly an entire collection of his art in the second floor of his house, Munch lived in fear of a Nazi confiscation. Seventy-one of the paintings previously taken by the Nazis had been returned to Norway through purchase by collectors (the other eleven were never recovered), including The Scream and The Sick Child, and they too were hidden from the Nazis.

Death and Legacy

Edvard Munch died in his house at Ekely near Oslo on 23 January 1944, about a month after his 80th birthday. His Nazi-orchestrated funeral suggested to Norwegians that he was a Nazi sympathizer, a kind of appropriation of the independent artist. The city of Oslo bought the Ekely estate from Munch’s heirs in 1946; his house was demolished in May 1960.

Edvard Munch’s oeuvre consists of over 1,000 works. While he painted in a variety of different styles throughout his lifetime, Munch was notorious for depicting dark, psychological, and haunting themes. A transitional figure in modern art, Munch’s work shows signs of both impressionism and expressionism. Munch’s Starry Night and the orange skies in Anxiety are reminiscent of the impressionist style of Van Gogh. The flowing waves in his landscape paintings are reminiscent of the later work of Dali.

Edvard was a leader in the revolt against the naturalistic dictates of 19th-century academic painting and also went beyond the naturalism still inherent in Impressionism. His concentration on emotional essentials sometimes led to radical simplifications of form and an expressive, rather than descriptive, use of color. All these tendencies were taken up by a number of younger artists, notably the leading proponents of German Expressionism. Perhaps his most direct formal influence on subsequent art can be seen in the area of the woodcut. His most profound legacy to modern art, however, lay particularly in his sense of art’s purpose to address universal aspects of human experience. Munch was heir to the traditional mysticism and anxiety of northern European painting, which he re-created in a highly personal art of the archetypal and symbolic. His work continues to speak to the typically modern situation of the individual facing the uncertainty of a rapidly changing contemporary world.

Information Source: