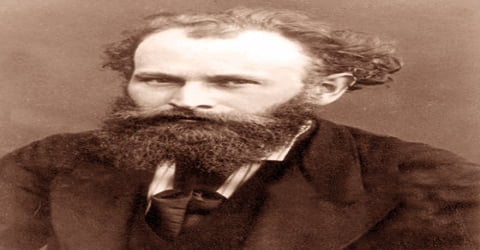

Biography of Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet – French modernist painter.

Name: Édouard Manet

Date of Birth: 23 January 1832

Place of Birth: Paris, France

Date of Death: 30 April 1883 (aged 51)

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Painter

Father: Auguste Manet

Mother: Eugenie-Desiree Fournier

Spouse/Ex: Suzanne Manet (m. 1863–1883)

Early Life

Édouard Manet, French painter who broke new ground by defying traditional techniques of representation and by choosing subjects from the events and circumstances of his own time, born in Paris on 23 January 1832, in the ancestral hôtel particular (mansion) on the rue des Petits Augustins (now rue Bonaparte) to an affluent and well-connected family. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life and a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born in an affluent family of diplomats and magistrates, he grew up to be the most controversial painter of his time. His father wanted him to build a career in law but Manet devoted himself to his passion for art. He was one of the key figures in the transition of art from ‘Realism to Impressionism’. His important works like ‘Olympia’ and ‘The Luncheon on the Grass’ caused great controversy. While traveling across Germany, Netherlands, and Italy; he was influenced by the styles of Spanish and Dutch artists. Although Manet had been influenced by the impressionist Style, he favored exhibiting arts in the Paris Salon rather than at independent exhibitions. After being rejected from the International Exhibition of 1867, he opened his own exhibition where he got his first contacts with future impressionist painters, like Degas.

His Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), exhibited in 1863 at the Salon des Refusés, aroused the hostility of critics and the enthusiasm of the young painters who later formed the nucleus of the Impressionist group. His other notable works include Olympia (1863) and A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882).

Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the start of modern art. The last 20 years of Manet’s life saw him form bonds with other great artists of the time, and develop his own style that would be heralded as innovative and serve as a major influence for future painters.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Édouard Manet was born in Paris, France, on January 23, 1832, to Auguste Édouard Manet and Eugénie Désirée Manet in an affluent family. His mother was Eugenie-Desiree Fournier, the daughter of Charles Bernadotte, the Swedish crown prince while his father, Auguste Manet was a judge and wanted his son to study law. His uncle, Edmond Fournier, encouraged him to pursue painting and took young Manet to the Louvre.

In 1841 Manet enrolled at the secondary school, the Collège Rollin. In 1845, at the advice of his uncle, Manet enrolled in a special course of drawing where he met Antonin Proust, future Minister of Fine Arts and subsequent lifelong friend.

To fulfill his father’s wish, Manet embarked on a training vessel in the year 1848 to join the Navy in Rio de Janeiro. After failing twice in the entrance examination, his father eventually agreed to his dream of pursuing an art education. Upon his return, he failed to pass the Navy’s entrance examination.

His father finally gave in, and in 1850 Manet began studying figure painting in the studio of Thomas Couture, where he remained until 1856. Manet also traveled abroad and made many copies of classic paintings for both foreign and French public collections.

Manet traveled to Netherlands, Italy, and Germany from 1853 to 1856, during which he learned painting from Spanish artists like Francisco Jose de Goya and Diego Velazquez and Dutch painter Frans Hals. His travel experiences influenced his various styles and art forms. He derived inspirations from illustrious personalities like Goya, Caravaggio, Diego Velazquez, and Titian.

Personal Life

(Suzanne Leenhoff and her son Leon Leenhoff, by Édouard Manet)

After the death of his father in 1862, Edouard Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff in 1863, supposedly a mistress of his father. Leenhoff was a Dutch-born piano teacher two years Manet’s senior with whom he had been romantically involved for approximately ten years. Leenhoff initially had been employed by Manet’s father, Auguste, to teach Manet and his younger brother piano. In 1852, Leenhoff gave birth, out of wedlock, to a son, Leon Koella Leenhoff.

The boy posed for his father for the 1861 painting “Boy Carrying a Sword” and as a minor subject in “The Balcony.” Suzanne was the model for several paintings, including “The Reading.”

Edouard Manet was short, unusually handsome, and witty. He was remembered as kind and generous toward his friends. Still, many elements of his personality were in conflict. Although he was a revolutionary artist, he craved official honors; while he dressed fashionably, he spoke a type of slang that was at odds with his appearance and manners; and although his style of life was that of a member of the conservative (preferring to maintain traditions and resist change) classes, his political beliefs were liberal (open-minded and preferring change).

Career and Works

In 1850 Manet entered the studio of the classical painter Thomas Couture. Despite fundamental differences between teacher and student, Manet was to owe to Couture a good grasp of drawing and pictorial technique. In 1856, after six years with Couture, Manet set up a studio that he shared with Albert de Balleroy, a painter of military subjects. There he painted The Boy with Cherries (c. 1858) before moving to another studio, where he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1859). In 1856 he made short trips to The Netherlands, Germany, and Italy. Meanwhile, at the Louvre he copied paintings by Titian and Diego Velázquez and in 1857 made the acquaintance of the artist Henri Fantin-Latour, who was later to paint Manet’s portrait.

Later in his career, Manet moved on to creating artworks rather than simply focusing on themes. Two of his paintings the ‘Christ with Angels’ and ‘Christ Mocked’ brought him fame.

Manet’s entry for the Salon (annual public exhibition, or show) of 1859, the Absinthe Drinker, a romantic but daring work, was rejected. At the Salon of 1861, his Spanish Singer, one of a number of works of Spanish character painted in this period, not only was admitted to the Salon but won an honorable mention and the praise of the poet Théophile Gautier. This was to be Manet’s last success for many years.

For his painting “Concert in the Tuileries Gardens,” sometimes called “Music in the Tuileries,” Manet set up his easel in the open air and stood for hours while he composed a fashionable crowd of city dwellers. When he showed the painting, some thought it was unfinished, while others understood what he was trying to convey. Perhaps his most famous painting is “The Luncheon on the Grass,” which he completed and exhibited in 1863. The scene of two young men dressed and sitting alongside a female nude alarmed several of the jury members making selections for the annual Paris Salon, the official exhibit hosted by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Due to its perceived indecency, they refused to show it. Manet was not alone, though, as more than 4,000 paintings were denied entry that year. In response, Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés to exhibit some of those rejected works, including Manet’s submission.

Manet became friends with the Impressionists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro through another painter, Berthe Morisot, who was a member of the group and drew him into their activities. The supposed grand-niece of the painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Morisot had her first painting accepted in the Salon de Paris in 1864, and she continued to show in the salon for the next ten years.

(Music in the Tuileries, 1862)

From 1862 to 1865 Manet took part in exhibitions organized by the Martinet Gallery. In 1863 the jury of the Salon rejected his Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, a work whose technique was entirely revolutionary, and so Manet instead exhibited it at the Salon des Refusés (established to exhibit the many works rejected by the official Salon). Although inspired by works of the Old Masters Giorgione’s Pastoral Concert (c. 1510) and Raphael’s Judgment of Paris (c. 1517–20) this large canvas aroused loud disapproval and began for Manet that “carnival notoriety” from which he would suffer for most of his career.

“The Luncheon on the Grass” (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe), 1863

In the 1860s, Manet was criticized by many critics for his ‘Luncheon on the Grass’ where a woman is shown in nude whereas two men are presented in full dress. Many were shocked at the odd ways of its depiction so the painting was rejected by the Paris salon. Yet again, the painting, ‘Olympia’ that showed a self-assured prostitute raged scandals at the Paris Salon. His photographic lighting and roughly painted style was modern and posed challenges to renaissance works. Although his arts anticipated and influenced the impressionist style, he abstained from impressionist exhibitions, since he favored salon exhibitions.

At the Salon of 1865, his painting “Olympia” created two years earlier, caused a scandal. The painting’s reclining female nude gazes brazenly at the viewer and is depicted in a harsh, brilliant light that obliterates interior modeling and turns her into an almost two-dimensional figure. This contemporary odalisque which the French statesman Georges Clemenceau was to install in the Louvre in 1907 was called indecent by critics and the public. In his vexation, Manet left in August 1865 for Spain, but, disliking the food and frustrated by his total lack of knowledge of the language, he did not stay long.

Manet became the friend and colleague of Berthe Morisot in 1868. She is credited with convincing Manet to attempt Plein air painting, which she had been practicing since she was introduced to it by another friend of hers, Camille Corot. They had a reciprocating relationship and Manet incorporated some of her techniques into his paintings. In 1874, she became his sister-in-law when she married his brother, Eugène.

In 1866, after the Salon jury had rejected two of Manet’s works, novelist Émile Zola (1840–1902) came to his defense with a series of articles filled with strongly expressed praise. In 1867 Zola published a book that predicted, “Manet’s place is destined to be in the Louvre.” (The Louvre, in Paris, is the largest and most famous art museum in the world.) In May 1868 Manet, at his own expense, exhibited fifty of his works at the Paris World’s Fair; he felt that his paintings had to be seen together in order to be fully understood.

When a large number of his works were rejected for the Universal Exposition of 1867, Manet, in imitation of Gustave Courbet, who had the same idea, had a stall erected at the corner of the Place de l’Alma and the Avenue Montaigne, where in May he exhibited a group of works, including his paintings of toreadors and bullfights. He showed about 50 paintings, but these were not received any more favorably than before. His work from this period was varied in character, but in general, it seems to represent a greater concern with close relations of tone and complexities of illumination and atmosphere, sometimes exhibiting freedom of handling comparable to that in Music in the Tuileries Gardens.

(The Cafe Concert, 1878)

Some of Manet’s best-loved works are his cafe scenes. His completed paintings were often based on small sketches he made while out socializing. These works, including “At the Cafe,” “The Beer Drinkers” and “The Cafe Concert,” among others, depict 19th-century Paris. Unlike conventional painters of his time, he strove to illuminate the rituals of both common and bourgeoisie French people. His subjects are reading, waiting for friends, drinking and working. In stark contrast to his cafe scenes, Manet also painted the tragedies and triumphs of war.

Manet painted the upper class enjoying more formal social activities. In Masked Ball at the Opera, Manet shows a lively crowd of people enjoying a party. Men stand with top hats and long black suits while talking to women with masks and costumes. He included portraits of his friends in this picture. His 1868 painting The Luncheon was posed in the dining room of the Manet house. He depicted other popular activities in his work. In “The Races at Longchamp”, an unusual perspective is employed to underscore the furious energy of racehorses as they rush toward the viewer. In Skating, Manet shows a well-dressed woman in the foreground, while others skate behind her. Always there is the sense of active urban life continuing behind the subject, extending outside the frame of the canvas.

(The Races at Longchamp, 1864)

In View of the International Exhibition, soldiers relax, seated and standing, prosperous couples are talking. There is a gardener, a boy with a dog, a woman on horseback in short, a sample of the classes and ages of the people of Paris.

In 1870, Manet served as a soldier during the Franco-German War and observed the destruction of Paris. His studio was partially destroyed during the siege of Paris, but to his delight, an art dealer named Paul Durand-Ruel bought everything he could salvage from the wreckage for 50,000 francs.

Toward the end of the 1870s, Manet returned to the figures of the early years. Perhaps his greatest work was his last major one, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. In 1872 he visited The Netherlands, where he was much influenced by the works of Frans Hals. As a result, Manet painted Le Bon Bock (1873; The Good Point), which achieved considerable success at the Salon exhibition of 1873.

Manet painted his most luminous plein-air picture, Boating (1874), which was set in Le Petit Gennevilliers and depicted two figures seated in the sun in a boat. It was also at Argenteuil that Manet painted Monet Painting on His Studio Boat (1874). Although he was friendly with Monet and the other Impressionists, Manet would not participate in their independent exhibitions and continued to submit his paintings to the official Salon. When The Artist and Laundry were both rejected by the Salon in 1875, Manet exhibited them along with other paintings in his studio.

In his mid-forties, Manet’s health deteriorated, and he developed severe pain and partial paralysis in his legs. In 1879 he began receiving hydrotherapy treatments at a spa near Meudon intended to improve what he believed was a circulatory problem, but in reality, he was suffering from locomotor ataxia, a known side-effect of syphilis. In 1880, he painted a portrait there of the opera singer Émilie Ambre as Carmen. Ambre and her lover Gaston de Beauplan had an estate in Meudon and had organized the first exhibition of Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian in New York in December 1879.

(Nana, 1877, Hamburger Kunsthalle)

When painting Nana (1877), Manet was inspired by the character of a woman of the demimonde whom Zola first introduced in his novel L’Assommoir (1877; The Drunkard); in that same year he painted Plum Brandy, one of his major works, in which a solitary woman rests her elbow on the marble top of a café table. He followed these works with The Blonde with Bare Breasts (c. 1878), in which the pearl-white flesh tones gleam with light, and Chez le Père Lathuille (1879), another of Manet’s major works, set in a restaurant near the Café Guerbois in Clichy.

In 1881 Manet was admitted to membership in the Legion of Honor, an award he had long dreamed of. By then he was seriously ill, and walking became increasingly difficult for him. In his weakened condition, he found it easier to handle pastels than oils, and he produced a great many flower pieces and portraits (paintings of people, especially their faces) in that medium. In early 1883 his left leg was amputated (cut off), but this did not prolong his life.

In January 1884 a posthumous exhibition of Manet’s work was held in the Salle de Melpomène of the École des Beaux-Arts. True to his admiration for the artist, Zola wrote the preface to the catalog. It was after this memorial exhibition that Manet’s paintings began to gain prominence.

Awards and Honor

In 1875, Edgar Allan Poe included lithographs by Edouard Manet in his French edition, The Raven, alongside translation by Mallarme.

In the year 1881, Edouard Manet was awarded the Legion d’honneur by the French government after his friend Antonin Proust put pressure on the government.

Death and Legacy

In April 1883, Manet’s left foot was amputated due to gangrene, and he died just eleven days later on April 30, 1883. He is buried in the Passy Cemetery in Paris. His public career lasted from 1861, the year of his first participation in the Salon, until his death in 1883. His extant works, as cataloged in 1975 by Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, comprise 430 oil paintings, 89 pastels, and more than 400 works on paper.

Manet’s debut as a painter met with a critical resistance that did not abate until near the end of his career. Although the success of his memorial exhibition and the eventual critical acceptance of the Impressionists with whom he was loosely affiliated raised his profile by the end of the 19th century, it was not until the 20th century that his reputation was secured by art historians and critics. Manet’s disregard for traditional modeling and perspective made a critical break with academic painting’s historical emphasis on illusionism. This flaunting of tradition and the official art establishment paved the way for the revolutionary work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

The roughly painted style and photographic lighting in Manet’s paintings were seen as specifically modern, and as a challenge to the Renaissance works he copied or used as source material. He rejected the technique he had learned in the studio of Thomas Couture in which a painting was constructed using successive layers of paint on a dark-toned ground in favor of a direct, alla prima method using opaque paint on a light ground. The novel at the time, this method made possible the completion of a painting in a single sitting. It was adopted by the Impressionists and became the prevalent method of painting in oils for generations that followed. Manet’s work is considered “early modern”, partially because of the opaque flatness of his surfaces, the frequent sketchlike passages, and the black outlining of figures, all of which draw attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

Manet also influenced the path of much 19th- and 20th-century art through his choice of subject matter. His focus on modern, urban subjects which he presented in a straightforward, almost detached manner distinguished him still more from the standards of the Salon, which generally favored narrative and avoided the gritty realities of everyday life. Manet’s daring, unflinching approach to his painting and to the art world assured both him and his work a pivotal place in the history of modern art.

The late Manet painting, Le Printemps (1881), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $65.1 million, setting a new auction record for Manet, exceeding its pre-sale estimate of $25–35 million at Christie’s on 5 November 2014. The previous auction record was held by Self-Portrait With Palette which sold for $33.2 million at Sotheby’s on 22 June 2010.

Information Source: