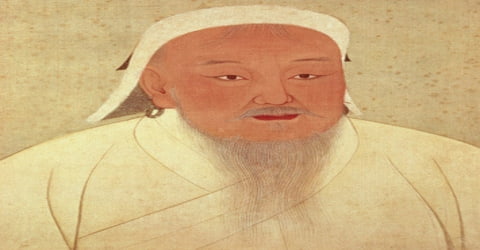

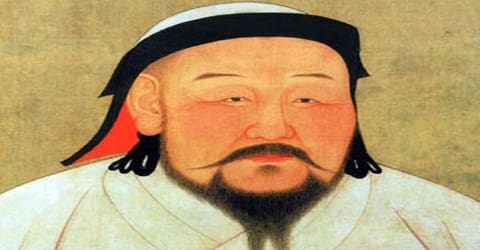

Biography of Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan – The founder and first Great Khan of the Mongol Empire.

Name: Genghis Khan

Date of Birth: 1162, Delüün Boldog

Place of Birth: Khentii Mountains, Khamag Mongol

Date of Death: August 18, 1227 (aged c. 65)

Place of Death: Yinchuan, Western Xia

Founder/Co-Founder: Mongol Empire

Father: Yesügei

Mother: Hoelun

Religion: Tengrism

Spouse: Börte Üjin Khatun, Yisui, Kunju Khatun, Khulan Khatun, Yesugen Khatun, Yesulun Khatun, Isukhan Khatun, Gunju Khatun, Abika Khatun, Gurbasu Khatun, Chaga Khatun, Moge Khatun

Children: Alakhai Bekhi, Alaltun, Chagatai Khan, Checheikhen, Gelejian, Jochi Khan, Khochen Beki, Ögedei Khan, Tolui, Tümelün

Early Life

Genghis Khan was the legendary political leader, who is famous even today for having established the powerful Mongol dynasty. He was born “Temujin” in Mongolia around 1162. He came to power by uniting many of the nomadic tribes of Northeast Asia. After founding the Empire and being proclaimed “Genghis Khan”, he launched the Mongol invasions that conquered most of Eurasia. Campaigns initiated in his lifetime include those against the Qara Khitai, Caucasus, and Khwarazmian, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. These campaigns were often accompanied by large-scale massacres of the civilian populations – especially in the Khwarazmian and Western Xia controlled lands. By the end of his life, the Mongol Empire occupied a substantial portion of Central Asia and China.

Having faced destitution at a very tender age, he grew up with a hunger for power and respect. Since his father died when he was but a small boy, his mother taught him everything about Mongolian politics, where no tribe was on good terms with the other. The young man gradually began his conquests, and was eventually successful in bringing all powerful tribes under one umbrella. He is known to this day for his religious tolerance and general protective demeanour. This famous ruler is the symbol of patriotism in Mongolia, and his name and face are used on every product in the country, to help it sell.

Before Genghis Khan died he assigned Ögedei Khan as his successor. Later his grandsons split his empire into khanates. Genghis Khan died in 1227 after defeating the Western Xia. By his request, his body was buried in an unmarked grave somewhere in Mongolia. His descendants extended the Mongol Empire across most of Eurasia by conquering or creating vassal states in all of modern-day China, Korea, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and substantial portions of Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia. Many of these invasions repeated the earlier large-scale slaughters of local populations. As a result, Genghis Khan and his empire have a fearsome reputation in local histories.

Though he is still a popular figure in the nation he laid the foundation of, in countries like China, people hold mixed sentiments about the leader. While his empire, which was later called the ‘Yuan dynasty’, helped bring together most of China, his conquests also caused the death of many people. In other parts of the world like the Middle East, this ruler is still abhorred, for having destroyed so many lives. However, whatever sentiments people hold, this leader still remains one of the most important figures in the history of Mongolia and the world.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Genghis Khan, Genghis also spelled Chinggis, Chingis, Jenghiz, or Jinghis, original name Temüjin, also spelled Temuchin, was probably born in 1162 in Delüün Boldog, near the mountain Burkhan Khaldun and the rivers Onon and Kherlen in modern-day northern Mongolia, close to the current capital Ulaanbaatar. He was the second son of his father Yesügei who was a Kiyad chief prominent in the Khamag Mongol confederation and an ally of Toghrul of the Keraite tribe. Temüjin was the first son of his mother Hoelun. According to the Secret History, Temüjin was named after the Tatar chief Temüjin-üge whom his father had just captured.

According to legend, his birth was auspicious, because he came into the world holding a clot of blood in his hand. He is also said to have been of divine origin, his first ancestor having been a gray wolf, “born with a destiny from heaven on high.” Yet his early years were anything but promising. When he was nine, Yesügei, a member of the royal Borjigin clan of the Mongols, was poisoned by a band of Tatars, another nomadic people, in continuance of an old feud.

Temujin lived with his parents, as well as his siblings Hasar, Hachiun, Temüge, Begter, Temülen, and Belgutei. While Hasar, Temüge, Temülen, and Hachiun, were his own siblings, Begter and Belgutei were half-brothers. After Yesügei was betrayed and killed by representatives of the ‘Tatar’ tribe, Temujin wanted to become the chief. However, he was rejected because he was very young, and the whole family was left to fend for themselves. For a long time, the family lived in dire poverty, foraging for food all by themselves.

In a raid around 1177, Temujin was captured by his father’s former allies, the Tayichi’ud, and enslaved, reportedly with a cangue (a sort of portable stocks). With the help of a sympathetic guard, he escaped from the ger (yurt) at night by hiding in a river crevice. The escape earned Temüjin a reputation. Soon, Jelme and Bo’orchu joined forces with him. They and the guard’s son Chilaun eventually became generals of Genghis Khan.

Upon hearing of his father’s death, Temujin returned home to claim his position as clan chief. However, the clan refused to recognize the young boy’s leadership and ostracized his family of younger brothers and half-brothers to near-refugee status. The pressure on the family was great, and in a dispute over the spoils of a hunting expedition, Temujin quarreled with and killed his half-brother, Bekhter, confirming his position as head of the family.

Personal Life

As previously arranged by his father, Temüjin married Börte of the Onggirat tribe when he was around 16 in order to cement alliances between their two tribes. Soon after the marriage, Börte was kidnapped by the Merkits and reportedly given away as a wife. Temüjin rescued her with the help of his friend and future rival, Jamukha, and his protector, Toghrul of the Keraite tribe. She gave birth to a son, Jochi (1185–1226), nine months later, clouding the issue of his parentage. Despite speculation over Jochi, Börte would be Temüjin’s only empress, though he did follow tradition by taking several morganatic wives. Börte had three more sons, Chagatai (1187–1241), Ögedei (1189–1241), and Tolui (1190–1232). However, only his male children with Borte qualified for succession in the family.

This legendary ruler followed ‘Tengrism’, a religion unique to Central Asia, but he was tolerant of all other beliefs and was even eager to learn and practice their teachings.

Genghis later took about 500 secondary wives and “consorts”, but Börte continued to be his life companion. He had many other children with those other wives, but they were excluded from the succession, only Börte’s sons were considered to be his heirs. However, a Tatar woman named Yisui, taken as a wife when her people were conquered by the Mongols, eventually came to be given almost as much prominence as Börte, despite originally being only one of his minor wives. The names of at least six daughters are known, and while they played significant roles behind the scenes during his lifetime, no documents have survived that definitively provide the number or names of daughters born to the consorts of Genghis Khan.

Career and Works

When Temujin was about 20, he was captured in a raid by former family allies, the Taichi’uts, and temporarily enslaved. He escaped with the help of a sympathetic captor and joined his brothers and several other clansmen to form a fighting unit. Temujin began his slow ascent to power by building a large army of more than 20,000 men. He set out to destroy traditional divisions among the various tribes and unite the Mongols under his rule.

Temüjin initially became a close associate to his father’s blood brother, Toghrul, the ruler of the ‘Khereid’ tribe. Soon, the former began rising to power, and his greatest opposition came from his childhood friend, political leader of the ‘Jadaran’ tribe, Jamukha.

As Jamukha and Temüjin drifted apart in their friendship, each began consolidating power, and they became rivals. Jamukha supported the traditional Mongolian aristocracy, while Temüjin followed a meritocratic method, and attracted a broader range and lower class of followers. Following his earlier defeat of the Merkits, and a proclamation by the shaman Kokochu that the Eternal Blue Sky had set aside the world for Temüjin, Temüjin began rising to power.

In 1186, Temüjin became the ‘Khan’ of the Mongols, causing his friend-turned-rival, Jamukha to launch an attack using thirty thousand soldiers, the following year. In the ‘Battle of Dalan Balzhut’, led by Jamakha, Temujin was defeated. However, he gained many followers, owing to the cruel treatment meted out by Jamukha.

With powerful allies and a force of his own, Temüjin routed the Merkit, with the help of a strategy by which Temüjin was regularly to scotch the seeds of future rebellion. He tried never to leave an enemy in his rear; years later, before attacking China, he would first make sure that no nomad leader survived to stab him in the back. Not long after the destruction of the Merkit, he treated the nobility of the Jürkin clan in the same way. These princes, supposedly his allies, had profited by his absence on a raid against the Tatars to plunder his property.

Temüjin exterminated the clan nobility and took the common people as his own soldiery and servants. When his power had grown sufficiently for him to risk a final showdown with the formidable Tatars, he first defeated them in battle and then slaughtered all those taller than the height of a cart axle. Presumably, the children could be expected to grow up ignorant of their past identity and to become loyal followers of the Mongols. When the alliance with Toghril of the Kereit, at last, broke down and Temüjin had to dispose of this obstacle to supreme power, he dispersed the Kereit people among the Mongols as servants and troops.

Around the year 1197, Jin initiated an attack against their formal vassal, the Tatars, with help from the Keraites and Mongols. Temüjin commanded part of this attack, and after victory, he and Toghrul were restored by Jin to positions of power. Jin bestowed Toghrul with the honorable title of Ong Khan, and Temüjin with a lesser title of j’aut quri.

Around 1200, the main rivals of the Mongol confederation (traditionally the “Mongols”) were the Naimans to the west, the Merkits to the north, the Tanguts to the south, and Jin to the east.

Around 1190, Temujin created a code of law, called ‘Yassa’, to rule his subjects. The ‘Yassa’ was never made public so that it could be changed as when it was deemed necessary. When the Jin dynasty attacked their earlier ally, the Tatars, in 1197, Temujin and his ally Toghrul offered military help. The Jin dynasty won, and their accomplices were honored with the titles ‘j’aut quri’, and ‘Ong Khan’, respectively.

Through a combination of outstanding military tactics and merciless brutality, Temujin avenged his father’s murder by decimating the Tatar army and ordered the killing of every Tatar male who was more than approximately 3 feet tall (taller than the linchpin, or axle pin, of a wagon wheel). Temujin’s Mongols then defeated the Taichi’ut using a series of massive cavalry attacks, including having all of the Taichi’ut chiefs boiled alive. By 1206, Temujin had also defeated the powerful Naiman tribe, thus giving him control of central and eastern Mongolia.

The break with Jamuka brought about a polarization within the Mongol world that was to be resolved only with the disappearance of one or the other of the rivals. Jamuka has no advocate in history. The Secret History has much to tell about him, not always unsympathetically, but it is essentially the chronicle of Temüjin’s family; and Jamuka appears as the enemy, albeit sometimes a reluctant one. He is an enigma, a man of sufficient force of personality to lead a rival coalition of princes and to get himself elected gur-khān, or supreme khan, by them. Yet he was an intriguer, a man to take the short view, ready to desert his friends, even turn on them, for the sake of a quick profit. But for Temüjin, it might have been within Jamuka’s power to dominate the Mongols, but Temüjin was incomparably the greater man; and the rivalry broke Jamuka.

Senggum, son of Toghrul (Wang Khan), envied Genghis Khan’s growing power and affinity with his father. He allegedly planned to assassinate Genghis Khan. Although Toghrul was allegedly saved on multiple occasions by Genghis Khan, he gave in to his son and became uncooperative with Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan learned of Senggum’s intentions and eventually defeated him and his loyalists.

In 1201, a khuruldai elected Jamukha as Gür Khan, “universal ruler”, a title used by the rulers of the Qara Khitai. Jamukha’s assumption of this title was the final breach with Genghis Khan, and Jamukha formed a coalition of tribes to oppose him. Before the conflict, several generals abandoned Jamukha, including Subutai, Jelme’s well-known younger brother. After several battles, Jamukha was turned over to Genghis Khan by his own men in 1206.

In 1204, Temujin defeated Kuchlug, the ruler of Naiman tribe, who later took over the ‘Kara-Khitan Khanate’.

According to the Secret History, Genghis Khan again offered his friendship to Jamukha. Genghis Khan had killed the men who betrayed Jamukha, stating that he did not want disloyal men in his army. Jamukha refused the offer, saying that there can only be one sun in the sky, and he asked for a noble death. The custom was to die without spilling blood, specifically by having one’s back broken. Jamukha requested this form of death, although he was known to have boiled his opponents’ generals alive.

This victory consolidated Temujin’s power as a Mongol ruler, and he was named ‘Genghis Khan’ by a council of Mongol chiefs, known as ‘Kurultai’.

As a ruler, he was eager to learn new tactics, and carefully studied the thought process of his rivals before attacking them. Thus by 1206, he had brought under his control, the tribes of Khereids, Naimans, Mongols, and the Tatars.

From 1207-10, Genghis fought several battles against the ‘Western Xia’ empire, where finally the ruler surrendered to the Mongol leader and became a vassal. Even the Uyghur tribe was captured and their officials were appointed as administrators in the Mongol dynasty.

The early success of the Mongol army owed much to the brilliant military tactics of Genghis Khan, as well as his understanding of his enemies’ motivations. He employed an extensive spy network and was quick to adopt new technologies from his enemies. The well-trained Mongol army of 80,000 fighters coordinated their advance with a sophisticated signaling system of smoke and burning torches. Large drums sounded commands to charge, and further orders were conveyed with flag signals. Every soldier was fully equipped with a bow, arrows, a shield, a dagger, and a lasso. He also carried large saddlebags for food, tools, and spare clothes.

The saddlebag was waterproof and could be inflated to serve as a life preserver when crossing deep and swift-moving rivers. Cavalrymen carried a small sword, javelins, body armor, a battle-ax or mace, and a lance with a hook to pull enemies off of their horses. The Mongols were devastating in their attacks. Because they could maneuver a galloping horse using only their legs, their hands were free to shoot arrows. The entire army was followed by a well-organized supply system of oxcarts carrying food for soldiers and beasts alike, as well as military equipment, shamans for spiritual and medical aid, and officials to catalog the booty.

As a result, by 1206, Genghis Khan had managed to unite or subdue the Merkits, Naimans, Mongols, Keraites, Tatars, Uyghurs, and other disparate smaller tribes under his rule. This was a monumental feat. It resulted in peace between previously warring tribes, and a single political and military force. The union became known as the Mongols. At a Khuruldai, a council of Mongol chiefs, Genghis Khan was acknowledged as Khan of the consolidated tribes and took the new title “Genghis Khan”. The title Khagan was conferred posthumously by his son and successor Ögedei who took the title for himself (as he was also to be posthumously declared the founder of the Yuan dynasty).

In 1207, he led his armies against the kingdom of Xi Xia and, after two years, forced it to surrender. In 1211, Genghis Khan’s armies struck the Jin Dynasty in northern China, lured not by the great cities’ artistic and scientific wonders, but rather the seemingly endless rice fields and easy pickings of wealth.

Soon, the Mongol ruler launched an attack on the ‘Jin Dynasty’ in Northern China, at the Badger Pass. The Jin emperor Xuanzong fled from his capital Zhongdu (present-day Beijing) and took up residence in a city called Kaifeng. Zhongdu was seized, and made a part of the Mongol empire by Genghis, in 1215. After his capture of Zhongdu, the Mongol leader continued on his conquests, and zeroed in upon the ‘Kara-Khitan Khanate’. Kuchlug, former ruler of the ‘Naiman’ tribe, who now had power over the ‘Kara-Khitan’, was defeated and killed by Genghis Khan’s small troop of 20,000 soldiers, led to war by general Jebe.

In 1219, Genghis Khan personally took control of planning and executing a three-prong attack of 200,000 Mongol soldiers against the Khwarizm Dynasty. The Mongols swept through every city’s fortifications with unstoppable savagery. Those who weren’t immediately slaughtered were driven in front of the Mongol army, serving as human shields when the Mongols took the next city. No living thing was spared, including small domestic animals and livestock. Skulls of men, women, and children were piled in large, pyramidal mounds. City after city was brought to its knees, and eventually, the Shah Muhammad and later his son was captured and killed, bringing an end to the Khwarizm Dynasty in 1221.

The Secret History reports it was only after the war against the Muslim empire of Khwārezm, in the region of the Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes), probably in late 1222, that Genghis Khan learned from Muslim advisers the “meaning and importance of towns.” And it was another adviser, formerly in the service of the Jin emperor, who explained to him the uses of peasants and craftsmen as producers of taxable goods. He had intended to turn the cultivated fields of northern China into grazing land for his horses.

A second attempt was made, this time to meet the emperor Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad, by sending a Muslim and two Mongol ambassadors, but this too was countered. Muhammad captured the ambassadors, shaved the heads of the Mongol, killed the Muslim, and sent the latter’s head back to Genghis. The Mongol emperor was enraged and attacked the ‘Khwarezmid Empire’ in order to take revenge. By 1222, along with his son Jochi, and his trusted generals, Jebe and Tolui, Genghis had defeated Muhammad, and destroyed all signs of the empire’s existence.

With the annihilation of the Khwarizm Dynasty, Genghis Khan once again turned his attention east to China. In 1226, the Mongol emperor returned and launched a counter-attack on the coalition. Within the next year Genghis destroyed Ning Hia, the Xia capital, and took over the whole empire. He ordered each and every member of the Xia ruling family to be killed, thus bringing about the extinction of the dynasty. Genghis Khan hadn’t quite extracted all the revenge he wanted for the Tangut betrayal, however, and ordered the execution of the imperial family, thus ending the Tangut lineage.

The famous Mongol emperor is best known for his creation of a decree called the ‘Yassa’. These rules of conduct were implemented in secret, so that there was scope to change them as and when required. Initially, the Yassa was followed only during wars, but it was later modified to include the empire’s lifestyle and cultural activities.

Honor

A memorial was constructed in his honor several years later in Xinjie Town. Since then the mausoleum has been moved to various locations to prevent it from destruction during wars.

In 1939 Chinese Nationalist soldiers took the mausoleum from its position at the ‘Lord’s Enclosure’ (Mongolian: Edsen Khoroo) in Mongolia to protect it from Japanese troops.

On October 6, 2004, a joint Japanese-Mongolian archaeological dig uncovered what is believed to be Genghis Khan’s palace in rural Mongolia, which raises the possibility of actually locating the ruler’s long-lost burial site.

Mongolia’s airport, located in the city of Ulaanbaatar, has been named ‘Chinggis Khaan International Airport’, as a tribute to the famous leader.

English poet F. L. Lucas has written a poem, ‘The End of Genghis’ where the dying leader retrospects on his life. There have also been novels, like Russian Vasili Yan’s ‘Jenghiz Khan and Batu Khan’, Telegu writer Thenneti Suri’s ‘Jenghiz Khan’, and British Conn Iggulden’s ‘The Conqueror’.

Death and Legacy

Genghis Khan died in August 1227, during the fall of Yinchuan, which is the capital of Western Xia. The cause of death is unknown, though there have been several speculations and stories woven around the incident. It is presumed that his body was buried near the Burkhan Khaldun Mountain and the Onon River, in the Mongolian province of Khentii. According to legend, the funeral escort killed anyone and anything they encountered to conceal the location of the burial site, and a river was diverted over Genghis Khan’s grave to make it impossible to find.

In early 1954, Genghis Khan’s bier and relics were returned to the Lord’s Enclosure in Mongolia. By 1956 a new temple was erected there to house them. In 1968 during the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards destroyed almost everything of value. The “relics” were remade in the 1970s and a great marble statue of Genghis was completed in 1989.

Before his death, Genghis Khan bestowed supreme leadership to his son Ogedei, who controlled most of eastern Asia, including China. The rest of the empire was divided among his other sons: Chagatai took over central Asia and northern Iran; Tolui, being the youngest, received a small territory near the Mongol homeland; and Jochi (who was killed before Genghis Khan’s death). Jochi and his son, Batu, took control of modern Russia and formed the Golden Horde. The empire’s expansion continued and reached its peak under Ogedei Khan’s leadership. Mongol armies eventually invaded Persia, the Song Dynasty in southern China, and the Balkans. Just when the Mongol armies had reached the gates of Vienna, Austria, leading commander Batu got word of the Great Khan Ogedei’s death and was called back to Mongolia. Subsequently, the campaign lost momentum, marking the Mongol’s farthest invasion into Europe.

As far as can be judged from the disparate sources, Genghis Khan’s personality was a complex one. He had great physical strength, the tenacity of purpose, and an unbreakable will. He was not obstinate and would listen to advice from others, including his wives and mother. He was flexible. He could deceive but was not petty. He had a sense of the value of loyalty, unlike Toghril or Jamuka. Enemies guilty of treachery toward their lords could expect short shrift from him, but he would exploit their treachery at the same time. He was religiously minded, carried along by his sense of a divine mission, and in moments of crisis, he would reverently worship the Eternal Blue Heaven, the supreme deity of the Mongols. So much is true of his early life.

Information Source: