Measuring ethane in the atmosphere reveals that the amount of methane released into the atmosphere from oil and gas wells and contributing to greenhouse warming is greater than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suggests, according to an international team of scientists who spent three years flying over three areas of the United States during all four seasons.

“Ethane is a gas that is only related to certain sources of methane,” said Zachary R. Barkley, a Penn State researcher in meteorology and atmospheric science. “However, methane is produced not only in oil, gas, and coal fields, but also in cow digestive systems, wetlands, landfills, and manure management. It is difficult to distinguish between methane produced by fossil fuels and natural methane.”

Because the Atmospheric Carbon and Transport (ACT) America data measured both methane and ethane, it was possible to quantify methane emissions from oil, gas, and coal sources. The researchers point out that methane identified as ethane can be reliably linked to fossil fuel sources; however, the ethane-to-methane ratio varies depending on the source.

Measuring ethane in the atmosphere shows that the amounts of methane going into the atmosphere from oil and gas wells and contributing to greenhouse warming are higher than suggested by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“ACT America was conceived as an effort to improve our ability to diagnose the sources and sinks of global greenhouse gases,” said Kenneth J. Davis, a Penn State professor of atmospheric and climate science. “We wanted to know how weather systems in the atmosphere move greenhouse gases around. There was no data to map the distribution of gases in weather systems prior to ACT.”

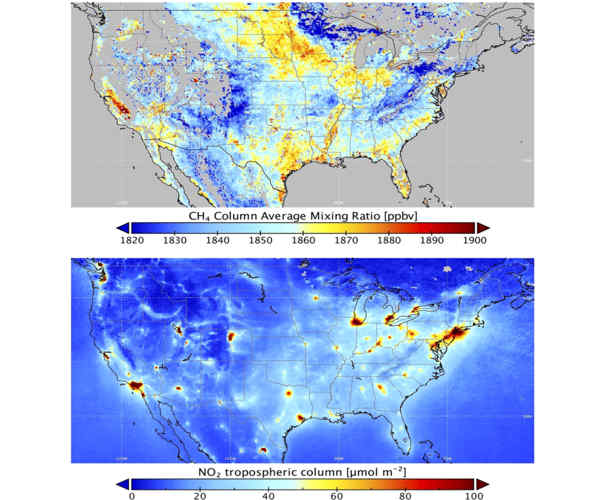

Researchers flew data collection missions over three regions of the United States from 2017 to 2019: the central Atlantic states of Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland; the central southern states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Mississippi; and the central midwestern states of Nebraska, South Dakota, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, and Mississippi. The researchers observed how weather systems moved carbon dioxide, methane, ethane, and other gases around in the atmosphere during all four seasons.

The researchers are not the first to suggest that methane estimates are too low, but they are the first, according to Barkley, to use ethane solely as a proxy. Although ethane is a greenhouse gas, it only remains in the atmosphere for a few months before breaking down into other compounds, as opposed to the ten years that methane does. Ethane is more of an issue for air pollution than it is for global warming.

“We didn’t look at any of the methane data at all,” he explained, “and we still see the same results as everyone else.” Another distinction is that previous airborne studies focused on small areas, such as emissions from single sites or fields. ACT-America examined multistate regions that accounted for more than two-thirds of US natural gas production.

“Ethane data consistently exceeds values that would be expected based on (US) EPA Oil and gas leak rate estimates by more than 50%,” the researchers write in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. When the researchers compare the combined fall, winter, and spring ethane emission estimates to an inventory of oil and gas methane emissions, they estimate that the oil and gas methane emissions are 48 percent to 76 percent higher than the EPA inventory values.

The researchers used ethane-to-methane ratios from oil and gas production basins for this study.

While carbon dioxide sources and sinks can be found all over the planet, ethane and methane emissions come from well-known locations on the ground. Deserts, oceans, and upland ecosystems produce very little ethane or methane. Emissions from active oil and gas fields are high. When estimating trace gas emissions, researchers typically start with their best guess and run multiple iterations to minimize the difference between observed and simulated atmospheric concentrations of these gases.

Barkley observes that while signals can be difficult to interpret at times, this is not the case in this study. “The data are there,” Barkley said. “When the smaller plume in the model is multiplied by two, it suddenly matches the real-time data.”