Photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting with sunlight is an environmentally friendly and promising technology that has generated a lot of interest in the production of renewable hydrogen.

Every green leaf can convert solar energy into chemical energy, which it then stores in chemical compounds. However, an important photosynthesis subprocess, solar hydrogen production, can already be technically imitated: Sunlight creates a current in a photoelectrode, which can then be used to split water molecules. This generates hydrogen, a versatile fuel that chemically stores solar energy and can release it when needed.

Photoelectrodes with many talents

Many teams are working on this vision at the HZB Institute for Solar Fuels. Their research is focused on developing efficient photoelectrodes. These are semiconductors that are highly active and stable in aqueous solutions. They can convert sunlight into electrical current as well as act as catalysts to accelerate water splitting. Bismuth vanadate is one of the best candidates for low-cost, high-efficiency photoelectrodes.

Basically, we know that just by immersing bismuth vanadate in the aqueous solution the chemical composition of the surface changes. Although there are a great many studies on BiVO4, it has not been clear until now exactly what implications this has on the surface electronic properties once they come into contact with the water molecules.

Dr. David Starr

What happens when in water?

“Basically, we know that just by immersing bismuth vanadate in the aqueous solution the chemical composition of the surface changes,” says Dr. David Starr of the HZB Institute for Solar Fuels. And his colleague Dr. Marco Favaro adds: “Although there are a great many studies on BiVO4, it has not been clear until now exactly what implications this has on the surface electronic properties once they come into contact with the water molecules.” In this work, they have now investigated this question.

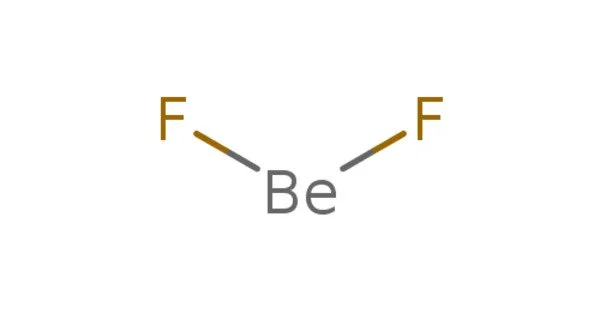

Doped BiVO4 under water vapor

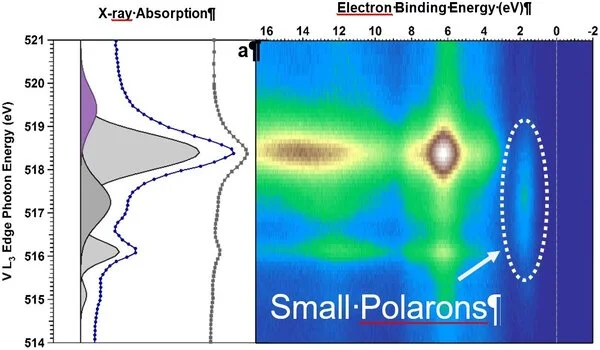

They studied single crystals of BiVO4 doped with molybdenum under water vapor with resonant ambient pressure photoemission spectroscopy at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. A team led by Giulia Galli at the University of Chicago then performed density functional theory calculations to help interpret the data and to untangle the contributions of individual elements and electron orbitals to the electronic states.

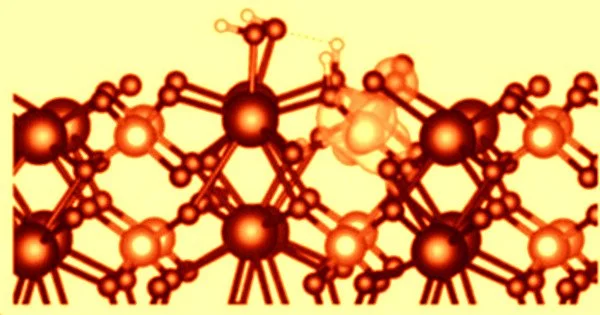

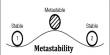

Polarons on the surface detected

“In situ resonant photoemission enabled us to understand how the electronic properties of our BiVO4 crystals changed during water adsorption,” says Favaro. The combination of measurements and calculations revealed that polarons, which are negatively charged localized states where water molecules can easily attach and then dissociate, can form as a result of excess charge generated by either doping or defects on certain surfaces of the crystal. The hydroxyl groups formed as a result of water dissociation aid in the stabilization of further polaron formation. According to Starr, “the excess electrons are localized as polarons at VO4 units on the surface.”

Knowledge based optimization

“What we don’t know for certain is what role polarons play in charge transfer. We still need to figure out whether they promote it and thus increase efficiency or, on the contrary, are an impediment “Starr admits as much. The findings shed light on processes that alter the surface chemical composition and electronic structure, and they may aid in the knowledge-based design of better photoanodes for green hydrogen production.