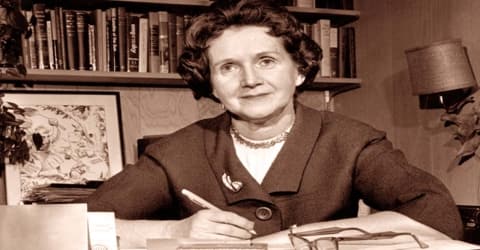

Biography of Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson – American marine biologist, author, and conservationist.

Name: Rachel Louise Carson

Date of Birth: May 27, 1907

Place of Birth: Springdale, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Date of Death: April 14, 1964 (aged 56)

Place of Death: Silver Spring, Maryland, U.S.

Occupation: Marine biologist, author, and environmentalist

Early Life

Rachel Louise Carson was an American marine biologist, author, and conservationist whose book Silent Spring and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental movement. She was born on May 27, 1907, in Springdale, Pennsylvania, and grew up on a 65-acre farm. As a child, she spent her days exploring nature and writing.

Carson graduated from Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University) in 1929, studied at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, and received her MA in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932.

She was hired by the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries to write radio scripts during the Depression and supplemented her income writing feature articles on natural history for the Baltimore Sun. She began a fifteen-year career in the federal service as a scientist and editor in 1936 and rose to become Editor-in-Chief of all publications for the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Carson began her career as an aquatic biologist in the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and became a full-time nature writer in the 1950s. She widely praised 1951 bestseller The Sea Around Us won her a U.S. National Book Award, recognition as a gifted writer, and financial security. Her next book, The Edge of the Sea, and the reissued version of her first book, Under the Sea Wind, were also bestsellers. This sea trilogy explores the whole of ocean life from the shores to the depths.

In 1952 she published her prize-winning study of the ocean, The Sea Around Us, which was followed by The Edge of the Sea in 1955. These books constituted a biography of the ocean and made Carson famous as a naturalist and science writer for the public. Carson resigned from government service in 1952 to devote herself to her writing.

Late in the 1950s, Carson turned her attention to conservation, especially some problems that she believed were caused by synthetic pesticides. The result was the book Silent Spring (1962), which brought environmental concerns to an unprecedented share of the American people. Although Silent Spring was met with fierce opposition by chemical companies, it spurred a reversal in national pesticide policy, which led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. It also inspired a grassroots environmental movement that led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Carson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Rachel Louise Carson was born May 27, 1907, in Springdale, Pennsylvania. She was the daughter of Maria Frazier (McLean) and Robert Warden Carson, an insurance salesman. A quiet child who kept to herself, she spent long hours learning about nature through her mother, a musician, and schoolteacher. Carson’s mother also inspired her daughter’s interest in literature, and at a very young age, Carson knew she wanted to become a writer. Carson sealed her ambitions to write when, at the age of ten, she published her first piece in a national children’s magazine.

“In every outthrust headland, in every curving beach, in every grain of sand there is the story of the earth,” said Carson.

Carson attended Springdale’s small school through tenth grade, then completed high school in nearby Parnassus, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1925 at the top of her class of forty-five students.

She originally studied English, but switched her major to biology in January 1928, though she continued contributing to the school’s student newspaper and literary supplement. Though admitted to graduate standing at Johns Hopkins University in 1928, she was forced to remain at the Pennsylvania College for Women for her senior year due to financial difficulties; she graduated magna cum laude in 1929. After a summer course at the Marine Biological Laboratory, she continued her studies in zoology and genetics at Johns Hopkins in the fall of 1929. She completed her postgraduate studies at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts.

After her first year of graduate school, Carson became a part-time student, taking an assistantship in Raymond Pearl’s laboratory, where she worked with rats and Drosophila, to earn money for tuition. After false starts with pit vipers and squirrels, she completed a dissertation project on the embryonic development of the pronephros in fish. She earned a master’s degree in zoology in June 1932.

In 1935, her father died suddenly, worsening their already critical financial situation and leaving Carson to care for her aging mother. After the five-year stint, Carson joined the Bureau of Fisheries in 1935. One of her first duties was to create a series of seven-minute radio programs about marine life. They were named “Romance Under the Waters.” Carson also began submitting articles on marine life in the Chesapeake Bay, based on her research for the series, to local newspapers and magazines.

Sitting for the civil service exam, she outscored all other applicants and, in 1936, became the second woman hired by the Bureau of Fisheries for a full-time professional position, as a junior aquatic biologist.

Personal Life

Carson first met Dorothy Freeman in the Summer of 1953 in Southport Island, Maine. Freeman had written to Carson welcoming her to the area when she had heard that the famous author was to become her neighbor. It was the beginning of an extremely close friendship that would last the rest of Carson’s life. Their relationship was conducted mainly through letters, and during summers spent together in Maine. Over the course of 12 years, they would exchange somewhere in the region of 900 letters. Many of these were published in the book Always, Rachel, published in 1995 by Beacon Press.

Shortly before Carson’s death, she and Freeman destroyed hundreds of letters. The surviving correspondence was published in 1995 as Always, Rachel: The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, 1952–1964: An Intimate Portrait of a Remarkable Friendship, edited by Freeman’s granddaughter. According to one reviewer, the pair “fit Carolyn Heilbrun’s characterization of a strong female friendship, where what matters is ‘not whether friends are homosexual or heterosexual, lovers or not, but whether they share the wonderful energy of work in the public sphere’.”

Career and Works

In 1936 Carson served as an aquatic biologist with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. A year later Carson published a well-received essay in the national publication Atlantic Monthly, which would ultimately lead to her first book, Under the Sea Wind (1941). She soon became editor-in-chief of the Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, a department dedicated to the conservation (protection) of wildlife. During this time she honed her writing skills, which focused on wildlife conservation.

She worked there until 1952. Carson also helped the government during World War II by investigating undersea sounds to assist the Navy in developing submarine detection. In 1951 she published her second book, “The Sea Around Us,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica. This book became an immediate best-seller and made her a wealthy woman. The book won a National Book Award, stayed on The New York Times’ best-seller list for 81 weeks and ended up being translated into 32 languages. In 1955, Carson’s third book, “Under the Sea,” was published.

The following year Carson left the government to undertake full-time writing and research. As a scientist and as an observant human being, the overwhelming effects of technology upon the natural world increasingly disturbed her. She wrote at the time:

“I suppose my thinking began to be affected soon after atomic science (an energy process which can have an extreme effect on the environment) was firmly established … It was pleasant to believe that much of Nature was forever beyond the tampering reach of man: I have now opened my eyes and my mind. I may not like what I see, but it does no good to ignore it.”

By 1948, Carson was working on material for a second book and had made the conscious decision to begin a transition to writing full-time. That year, she took on a literary agent, Marie Rodell; they formed a close professional relationship that would last the rest of Carson’s career.

She wrote several other articles designed to teach people about the wonder and beauty of the living world, including “Help Your Child to Wonder,” (1956) and “Our Ever-Changing Shore” (1957), and planned another book on the ecology of life. Embedded within all of Carson’s writing was the view that human beings were but one part of nature distinguished primarily by their power to alter it, in some cases irreversibly.

Disturbed by the profligate use of synthetic chemical pesticides after World War II, Carson reluctantly changed her focus in order to warn the public about the long-term effects of misusing pesticides. In Silent Spring (1962) she challenged the practices of agricultural scientists and the government and called for a change in the way humankind viewed the natural world.

When Silent Spring appeared in 1962, the poetic pen and scientific mind of Carson produced an impact equaled by few scientists. In fact, she had aroused an entire nation. More than a billion dollars worth of chemical sprays were being sold and used in America each year. Carson traced the course of chlorinated hydrocarbons, a harmful substance found in the pesticides (chemicals used to protect crops from insects), through energy cycles and food chains. She learned that highly toxic (deadly) materials, contaminating the environment and lasting for many years in waters and soils, also tended to build up in the human body. Insect species that were the targets for these poisons began developing immunities (resistance) to pesticides, and because of these poisons in the insects, birds were not reproducing. In fact, the entire food chain and environmental balance were becoming disrupted because of these chemicals. Carson proposed strict limitations on spraying programs and an accelerated research effort to develop natural and biological controls for harmful insects.

Carson was attacked by the chemical industry and some in government as an alarmist but courageously spoke out to remind us that we are a vulnerable part of the natural world subject to the same damage as the rest of the ecosystem. Testifying before Congress in 1963, Carson called for new policies to protect human health and the environment.

The pesticide industry reacted with a massive campaign to damage the reputation of Carson and her findings. Firmly and gently, she spent the next two years educating the public at large.

“I think we are challenged as mankind has never been challenged before,” she once said, “to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves.”

Carson once stated in a television interview, “man’s endeavors to control nature by his powers to alter and to destroy would inevitably evolve into a war against himself, a war he would lose unless he came to terms with nature.”

Awards and Honor

(The Rachel Carson sculpture in Woods Hole)

Carson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter, on June 9, 1980. In 1973, Carson was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. A Pittsburgh bridge was also renamed in Carson’s honor as the Rachel Carson Bridge. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection State Office Building in Harrisburg is named in her honor.

(The Rachel Carson Bridge in Pittsburgh, mid-1999)

In 1969, the Coastal Maine National Wildlife Refuge became the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge; expansions will bring the size of the refuge to about 9,125 acres (3,693 ha). In 1985, North Carolina renamed one of its estuarine reserves in honor of Carson, in Beaufort.

The American Society for Environmental History has awarded the Rachel Carson Prize for Best Dissertation since 1993. Since 1998, the Society for Social Studies of Science has awarded an annual Rachel Carson Book Prize for “a book-length work of social or political relevance in the area of science and technology studies.”

The Rachel Carson sculpture in Woods Hole, Massachusetts was unveiled on July 14, 2013. Google created a Google Doodle for Carson’s 107th birthday on May 27, 2014. Carson was featured during the “HerStory” video tribute to notable women on U2’s tour in 2017 for the 30th anniversary of The Joshua Tree during a performance of “Ultraviolet (Light My Way)” from the band’s 1991 album Achtung Baby.

Death and Legacy

Carson died of breast cancer on April 14, 1964, in Silver Spring, Maryland. Her body was cremated and the ashes buried beside her mother at Parklawn Memorial Gardens, Rockville, Maryland. Some of her ashes were later scattered along the coast of Southport Island, near Sheepscot Bay, Maine.

Though her work was just beginning at the time of her death, through her pen Carson opened the eyes of a nation and inspired environmental activism in a country that was rapidly losing its own natural resources. Her witness for the beauty and integrity of life continues to inspire new generations to protect the living world and all its creatures.

Information Source: