Biography of Meister Eckhart

Meister Eckhart – German theologian, philosopher, and mystic.

Name: Eckhart von Hochheim

Date of Birth: c. 1260

Place of Birth: near Gotha, Landgraviate of Thuringia in the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany)

Date of Death: c. 1328

Place of Death: probably Avignon, the Kingdom of Arles in the Holy Roman Empire (now France)

Early Life

Miester Eckhart was born in 1260 at Hochheim, a village near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia (now central Germany) in the Holy Roman Empire and was named Eckhart von Hochheim. He was endowed with the honorific title of “meister” (master in German) after he obtained the academic title of ‘Magister in Theologia’ from the University of Paris. A theologian, preacher, mystic, writer, able orator and a renowned philosopher of the thirteenth-fourteenth century, Meister Eckhart’s life and the feat is no ordinary deed. His works, ideas, and contributions have kindled and captivated the curiosity of the modern readers. He is lauded for his theistic works and his unusual views on God that is grounded on his principle conviction “God is ‘No-thing’ but rather the Being that undergirds all reality – and we must become nothing to be one with God.”

Eckhart came into prominence during the Avignon Papacy, at a time of increased tensions between monastic orders, diocesan clergy, the Franciscan Order, and Eckhart’s Dominican Order of Preachers. In later life, he was accused of heresy and brought up before the local Franciscan-led Inquisition, and tried as a heretic by Pope John XXII. He seems to have died before his verdict was received.

Despite his dissident theological beliefs and ontological philosophies, his mysticism is still valued and respected. Although the Roman Catholic Church condemned him for his heretical theological ideas, Eckhart remained true to the teachings of the Church. Eckhart was one of the firsts to write inquisitive prose in German and introduce new terms and gradually with his work made German the language of democratic tracts.

He was well known for his work with pious lay groups such as the Friends of God and was succeeded by his more circumspect disciples John Tauler and Henry Suso. Since the 19th century, he has received renewed attention. He has acquired a status as a great mystic within contemporary popular spirituality, as well as considerable interest from scholars situating him within the medieval scholastic and philosophical tradition.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Meister Eckhart, English Master Eckhart, original name Johannes Eckhart, also called Eckhart von Hochheim, Eckhart also spelled Eckehart, was born in the village of Tambach, near Gotha, in the Landgraviate of Thuringia, perhaps between 1250 and 1260. He was initially known to have been born in a notable family of landlords, but this was later reported to be false and the origin of his family and early life remain ambiguous.

He got into the Order of Preachers (commonly known as Dominican order) at the age of 15. It is assumed that he received his education from the Studium Generale in Cologne founded by Albert the Great. It was also in Paris that he received a master’s degree (1302) and consequently was known as Meister Eckhart. In the year 1300, he went to Paris for higher studies and stayed there until 1303. He stayed there for three years and after returning to Erfurt, became the provincial of Saxony. In 1307 he was appointed the vicar-general for Bohemia, to set the demoralized monasteries there in order.

Career and Works

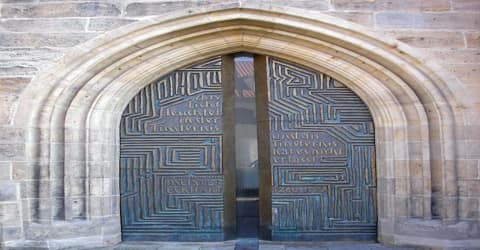

(The Meister Eckhart portal of the Erfurt Church)

On 14 May 1311, Eckhart was appointed by the general chapter held at Naples as a teacher at Paris. To be invited back to Paris for a second stint as magister was a rare privilege, previously granted only to Thomas Aquinas. Eckhart stayed in Paris for two academic years, until the summer of 1313, living in the same house as William of Paris. A passage in a chronicle of the year 1320, extant in manuscript (cf. Wilhelm Preger, i. 352–399), speaks of a prior Eckhart at Frankfurt who was suspected of heresy, and some have referred this to Meister Eckhart. It is unusual that a man under suspicion of heresy would have been appointed a teacher in one of the most famous schools of the order, but Eckhart’s distinctive expository style could well have already been under scrutiny by his Franciscan detractors.

Eckhart wrote four works in German that are usually called “treatises.” At about the age of 40, he wrote the Talks of Instruction, on self-denial, the nobility of will and intellect, and obedience to God. In the same period, he faced the Franciscans in some famous disputations on theological issues. In 1303 he became provincial (leader) of the Dominicans in Saxony, and three years later vicar of Bohemia. His main activity, especially from 1314, was preaching to the contemplative nuns established throughout the Rhine River valley. He resided in Strasbourg as a prior.

In the year 1313, Eckhart went to Strasbourg and served as an active preacher for Dominican communities from 1314-1322. In 1323, Eckhart settled in Cologne and started teaching at Studium Generale. During this time, he was accused of heresy by the archbishop, Hermann von Virneburg. However, Nicholas of Strasburg, who was the temporary in-charge of the Dominican monasteries in Germany, exonerated the charges.

Eckhart was accused of heresy after he returned to Cologne. Hermann von Virneburg made this accusation before the pope, but these accusations were not acknowledged. In February 1327 Eckhart stated in a public protest that he detested everything wrong and nothing of the kind could be found in any of his writings. In 1329 however, many of his works were regarded as heretical at the close of the statement the court stated that before Eckhart’s death he recanted everything he had falsely taught and preached, by subjecting himself and his works to the apostolic see.

In late 1323 or early 1324, Eckhart left Strasbourg for the Dominican house at Cologne. It is not clear exactly what he did here, though part of his time may have been spent teaching at the prestigious Studium in the city. Eckhart also continued to preach, addressing his sermons during a time of disarray among the clergy and monastic orders, the rapid growth of numerous pious lay groups, and the Inquisition’s continuing concerns over heretical movements throughout Europe.

The best-attested German work of this middle part of his life is the Book of Divine Consolation, dedicated to the Queen of Hungary. The other two treatises were The Nobleman and On Detachment. The teachings of the mature Eckhart describe four stages of the union between the soul and God: dissimilarity, similarity, identity, the breakthrough. At the outset, God is all, the creature is nothing; at the ultimate stage, “the soul is above God.” The driving power of this process is detachment.

Throughout the difficult months of late 1326, Eckhart had the full support of the local Dominican authorities, as evident in Nicholas of Strasbourg’s three official protests against the actions of the inquisitors in January 1327. On 13 February 1327, before the archbishop’s inquisitors pronounced their sentence on Eckhart, Eckhart preached a sermon in the Dominican church at Cologne, and then had his secretary read out a public protestation of his innocence. He stated in his protest that he had always detested everything wrong, and should anything of the kind be found in his writings, he now retracts. Eckhart himself translated the text into German, so that his audience, the vernacular public, could understand it. The verdict then seems to have gone against Eckhart. Eckhart denied competence and authority to the inquisitors and the archbishop and appealed to the Pope against the verdict. He then, in the spring of 1327, set off for Avignon.

Eckhart’s view on the relationship of God to the soul is considered unique. The unqualified deity, the Trinity (birth of the Eternal Lord), and the creation of the world are the three immediate moments which trail each other in not chronological sequence, but conceptual. In the divine essence, all creatures have a certain role to play. According to him, there is something of God in the illogical creature, but in the soul God is divine and only rational creatures can save the words spoken by God. Its better said as God is subjective in his resting place – soul and objective in the rest of the creation. The soul is considered the image of God with its chief powers, memory, reason, and will. This idea heads in the direction of Augustine. There is an innermost background of the soul, which Eckhart calls as a spark or little spark, which is something present in the soul superior to its own powers. In the real sense, this basis of the soul is the one related with the Deity. Since the soul has a subjective being, it must turn to God so that the crucial principle rooted in it may be truly realized. It is certain that it was made by God but just the creation of it is not enough; God must also come and exist in it. This has taken place without any encumbrance in the human soul of Christ but for all other souls, sin is an obstruction.

Eckhart’s main teachings were based on the fact that he expected all souls to be internally connected to God and to be led by Him, and in this, he emphasized that all the creatures will be led into positivity. His teachings were based on the mere idea of sublimity and purity. It was these influential positive teachings that made him such a strong and influential preacher.

In the year 1305, he composed the Opus tripartitum, a major work that contained three parts – the Opus propositionum (Work of Theses) which has more than 1,000 theses in 14 treatises, the Opus quaestionum (Work of Problems) and the Opus expositionum (Work of Interpretations). Meister Eckhart has written many Latin and German works. The Latin treatises are considered the most orthodox that includes 56 sermons, which has a long sermon on the Lord’s prayer, scriptural commentaries, fragments from his opium tripartitum, introduction to his commentary on Lombard’s sentences, the Parisian questions and his Paris debates. His works in German begins with four treatises – Talks of Instruction (written in 1290s), The Nobleman/Aristocrat, on detachment/disinterest and in the year 1308 – the Book of Divine Consolation written for the widow Queen Anne of Hungary after the death of her mother and murder of her father Albert I of Austria.

(A sculpture of Meister Eckhart, Bad Wörishofen, Germany)

Eckhart was one of the most influential 13th-century Christian Neoplatonists in his day and remained widely read in the later Middle Ages. Some early twentieth-century writers believed that Eckhart’s work was forgotten by his fellow Dominicans soon after his death. In 1960, however, a manuscript (“in agro dominico”) was discovered containing six hundred excerpts from Eckhart, clearly deriving from an original made in the Cologne Dominican convent after the promulgation of the bull condemning Eckhart’s writings, as notations from the bull are inserted into the manuscript. The manuscript came into the possession of the Carthusians in Basel, demonstrating that some Dominicans and Carthusians had continued to read Eckhart’s work.

It is also clear that Nicholas of Cusa, Archbishop of Cologne in the 1430s and 1440s, engaged in extensive study of Eckhart. He assembled, and carefully annotated, a surviving collection of Eckhart’s Latin works. As Eckhart was the only medieval theologian tried before the Inquisition as a heretic, the subsequent (1329) condemnation of excerpts from his works cast a shadow over his reputation for some, but followers of Eckhart in the lay group Friends of God existed in communities across the region and carried on his ideas under the leadership of such priests as John Tauler and Henry Suso.

Although Eckhart’s philosophy amalgamates Greek, Neoplatonic, Arabic, and Scholastic elements, it is unique. His doctrine, sometimes abstruse, always arises from one simple, personal mystical experience to which he gives a number of names. By doing so, he was also an innovator of the German language, contributing many abstract terms. In the second half of the 20th century, there was great interest in Eckhart among some Marxist theorists and Zen Buddhists.

Eckhart was largely forgotten from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, barring occasional interest from thinkers such as Angelus Silesius (1627–1677). For centuries, none of Eckhart’s writings were known except a number of sermons, found in the old editions of Johann Tauler’s sermons, published by Kachelouen (Leipzig, 1498) and by Adam Petri (Basel, 1521 and 1522).

Many of Eckhart’s works were filled with paradoxes. He refused to call God “god” and referred to Him as “deity”, stating that it is impossible to give God a finite definition and at the same time he mentioned that God is a finite being and that God cannot be defined as something absent or negative. He stated that the true way for the soul to attain salvation is by its unity with God. Such knowledge is given in the traditional teachings of the Church but according to Eckhart, the way to attain that unity with God does not necessarily agree with the formal preaching of the Church.

Death and Legacy

Eckhart’s death date is not confirmed but he is said to have died around January 28, 1328, in Avignon before he could hear his judgment of conviction.

Eckhart’s works were read widely throughout the 13th century and also by many people in the centuries to follow. His trial on heresy, however, shadowed his reputation. A very few of Eckhart’s works were known even after his death which is why it was very difficult to conclude what his views were. Eckhart wrote extensively on metaphysics and spiritual psychology.

In the fond remembrance of Meister Eckhart, The Eckhart Society has been built, which is an international society dedicated to promote and teach the principles of Meister Eckhart. The society aims in providing a complete study and research in the life, preaching, and writings of Eckhart. The main publication of this society is a yearbook, the “Jahrbuch der Meister-Eckhart-Gesellschaft” that is purely influenced by Eckhart’s studies. The chief language of this yearbook is German but has contributors from languages like English, French, Spanish and Italian. A website is also dedicated to the Meister where the writings, translations, articles, manuscripts, and books are available.

Information Source: