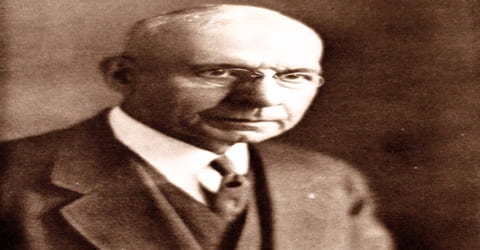

Biography of Louis Sullivan

Louis Sullivan – American architect.

Name: Louis Henry Sullivan

Date of Birth: September 3, 1856

Place of Birth: Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Date of Death: April 14, 1924 (aged 67)

Place of Death: Chicago, Illinois, United States

Occupation: Architect

Father: Patrick Sullivan

Mother: Andrienne List

Spouse/Ex: Azona Hattabaugh (m. 1899)

Early Life

An esteemed American architect, regarded as the spiritual father of modern American architecture and identified with the aesthetics of early skyscraper design Louis Sullivan was born on 3rd September 1856, in Boston, Massachusetts, the U.S. to a Swiss-born mother, née Andrienne List, and an Irish-born father, Patrick Sullivan. He has been called the “father of skyscrapers” and “father of modernism”. Sullivan is accredited for developing the aesthetics and dynamics for the first skyscraper. Some of his highly acclaimed and notable works include Auditorium Building, Chicago, the Guaranty Building, Buffalo, New York, and the Wainwright Building, St. Louis, Missouri.

Sullivan attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Beaux-Arts in Paris. His career reached its zenith during his partnership with Dankman Adler. At first, the partners designed many theatres, the most famous example of their work being the Auditorium Building in Chicago. The Wainwright Tomb, the mausoleum designed by Sullivan is regarded as a masterpiece. These buildings came at a time when steel was used to give strength to buildings, unlike before when the buildings were constructed with very thick “load-bearing” walls. Sullivan adapted by creating high-rises very different from the ones that were being constructed along with historical styles. He emphasized the height, keeping in mind the purpose of the construction.

Sullivan’s more than 100 works in collaboration (1879-95) with Dankmar Adler include the Auditorium Building, Chicago (1887-89); the Guaranty Building, Buffalo, New York (1894-95; now Prudential Building); and the Wainwright Building, St. Louis, Missouri (1890-91). Frank Lloyd Wright apprenticed for six years with Sullivan at the firm. In independent practice from 1895, Sullivan designed the Schlesinger & Mayer department store (1898-1904; now the Sullivan Center) in Chicago.

Sullivan believed in the Roman architect, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio’s credo “form ever follows function”, stressing on use rather than utility. But, he also used ornamentations as seen in the Carson Pirie Scott store, and the semi-circular arch was his favorite feature. His design of the polychrome modern Transportation Building earned him accolades for originality. After his partnership with Adler broke, he did not do well. He became erratic, undependable, impersonal, and an alcoholic. He became an inspiration for other Chicago architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Nickel, and Crombie Taylor.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Louis Sullivan, in full Louis Henry Sullivan, was born on 3rd September 1856, in Boston, Massachusetts, the U.S. to Patrick Sullivan and Andrienne List. His parents had immigrated to America in the late 1840s from Ireland and Switzerland respectively. He had an older brother, Albert Walter.

Sullivan studied in public schools in Boston and spent considerable time on his grandparents’ farm in South Reading. When his parents transferred to Chicago in 1869, he preferred to remain with his grandparents.

Sullivan was a bright and ambitious student; he was only 16 when he entered M.I.T. At the time, it was the only architectural school in the nation. After just one year, Sullivan left to work at an architectural firm in Philadelphia. Between 1874 and 1875, he studied at the influential École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. He also traveled to Rome and Florence in Italy, where he was struck by the awe and beauty of their historical buildings. Sullivan returned to America, eager to put his theoretical ideas into practice.

Personal Life

Louis Henry Sullivan married Mary Azona Hattabaugh, known as Margaret, in 1899, a 27-year-old divorcee, fifteen years younger than him. She left him 10 years later – the couple was childless.

Career and Works

Louis Sullivan returned to Chicago in 1875 and signed up as a draftsman for Joseph S. Johnston & John Edelman. Soon, he began to garner fame and admiration for his design for the interior decorative “fresco secco” stencils of the Moody Tabernacle. In 1879, Sullivan began his lifelong and incredibly successful partnership with Dankmar Adler, and together, they came to be considered as the leading gurus of theatre architecture. While most of their theaters were in Chicago, their fame won commissions as far west as Pueblo, Colorado, and Seattle, Washington (unbuilt). The culminating project of this phase of the firm’s history was the 1889 Auditorium Building (1886-90, opened in stages) in Chicago, an extraordinary mixed-use building that included not only a 4,200-seat theater, but also a hotel and an office building with a 17-story tower and commercial storefronts at the ground level of the building, fronting Congress and Wabash aAvenues.

Although Adler and Sullivan did substantial residential work, it was in the commercial work that they made their art-historic contribution. Most of their buildings were in Chicago, where the commercial expansion of the 1880s resulted in many commissions.

In the 1890s, the partners Adler and Sullivan designed The Schiller Building, the Chicago Stock Exchange Building, the Guaranty or Prudential Building, New York, and the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store, Chicago. His masterpiece, the Wainwright Tomb, a mausoleum in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, constructed for Charlotte Dickson Wainwright in 1892, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and became a St. Louis Landmark.

Sullivan’s bold geometrical lines and taller skyscrapers helped him stand out his contemporaries, who emulated older, established styles. Instead of mimicking these styles, Sullivan drew on his experiences at M.I.T. and in Europe and took a fresh and ingenious approach to architecture. ‘Form ever follows function’ or ‘Form follows function’, Sullivan said. By this, he means that the form of a building, such as its decoration, design or style, should arise from the function or purpose of a building, not the other way around.

Louis Sullivan developed his magnum opus, the Wainwright Tomb; in 1892 a monument dedicated to the memory of Charlotte Dickson Wainwright, in Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis. This building is not only listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but it is also a St. Louis Landmark. In 1893, Sullivan began designing his iconic polychrome modern Transportation Building for the “White City”, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The iconic duo of partners broke up in 1893, due to the severe economic depression that took over America, and Sullivan began encountering serious financial difficulties, and he gave into alcoholism.

Louis Sullivan’s development of the skyscraper is probably the best example of ‘form follows function’. Newly available steel supports allowed for buildings with more than a dozen stories, which dramatically reshaped the skylines of many industrial American cities. However, these designs were clunky and often resembled two or more traditionally sized buildings placed on top of each other. By applying the principle of ‘form follows function’, Sullivan developed a contemporary style that emphasized the use of new building practices and materials, as well as verticality and openness. His first major skyscraper, the Carson, Pirie and Scott Store, was finished in 1904. With its large glass windows on every side and tall steel support beams, it also brings to mind something else Louis Sullivan once said: ‘Our architecture reflects truly as a mirror.’

Another signature element of Sullivan’s work is the massive, semi-circular arch. Sullivan employed such arches throughout his career in shaping entrances, in framing windows, or as interior design. All of these elements are found in Sullivan’s widely admired Guaranty Building, which he designed while partnered with Adler. Completed in 1895, this office building in Buffalo, New York is in the Palazzo style, visibly divided into three “zones” of design: a plain, wide-windowed base for the ground-level shops; the main office block, with vertical ribbons of masonry rising unimpeded across nine upper floors to emphasize the building’s height; and an ornamented cornice perforated by round windows at the roof level, where the building’s mechanical units (such as the elevator motors) were housed. The cornice is covered by Sullivan’s trademark Art Nouveau vines and each ground-floor entrance is topped by a semi-circular arch.

During his later career, Sullivan’s most noteworthy projects were seven banks in many small Midwestern towns, beginning with the National Farmers’ (now Security) Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota. The Merchants’ National Bank in Grinnell, Iowa, completed in1914, has a relatively serious form, with intricate ornament. His last project was the facade for the Krause Music Store in Chicago, eight years later.

The middle-aged Sullivan became something of a recluse, seeking solace in writing and in visits to his winter cottage in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. His marriage in 1899 to Margaret Davies Hattabough did little to bring lasting happiness; they were separated in 1906 and divorced in 1917 without having had children. With declining income, Sullivan moved to progressively cheaper hotels in an effort to economize. By 1909 a lack of commissions reduced him to desperate straits; he was forced to sell his library and household effects. Perhaps an equal loss was the departure that year of Elmslie, his assistant for 20 years, who went to join forces in Minneapolis with William Gray Purcell, an architect who had worked briefly for Sullivan in 1903.

In 1924, Louis Sullivan’s autobiographical work, ‘The Autobiography of an Idea’, describing his childhood, and early career, and 19 plates for A System of Architectural Ornament According with a Philosophy of Man’s Powers, were published.

Awards and Honor

In 1844, Louis Sullivan was posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal by the American Institute of Architects in acknowledgment of his enduring contribution to the theory and practice of architecture.

Death and Legacy

Louis Henry Sullivan fell and died on 14th April 1924, while building a big skyscraper in Chicago. He left a wife, Mary Azona Hattabaugh, from whom he was separated. A modest headstone marks his final resting spot in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago’s Uptown and Lake View neighborhood. Later, a monument was erected in Sullivan’s honor, a few feet from his headstone.

One of the earliest skyscrapers in the world, the 10-storeyed Wainwright Building, in St. Louis, designed by Louis Sullivan, soared vertically from ground to cornice. It is one of “10 Buildings That Changed America”. The classic Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building (the Sullivan Center), in Chicago, had a corner visible from two avenues, designed by him. The ornamentation above the entrance was a distinct feature.

Louis Sullivan was a spokesman for the reform of architecture, an opponent of historical eclecticism, and did much to remake the image of the architect as a creative personality. His own designs are characterized by a richness of ornament. His importance lies in his writings as well as in his architectural achievements. These writings, which are subjective and metaphorical, suggest directions for architecture, rather than explicit doctrines or programs. Sullivan himself warned of the danger of mechanical theories of art.

Information Source: