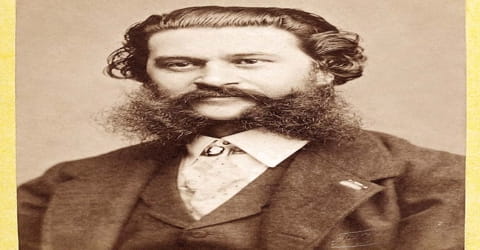

Biography of Johann Strauss Jr.

Johann Strauss Jr. – Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas.

Name: Johann Strauss Jr.

Date of Birth: October 25, 1825

Place of Birth: Neubau, Vienna, Austria

Date of Death: June 3, 1899

Place of Death: Vienna, Austria

Occupation: Composer

Father: Johann Strauss the Elder

Spouse/Ex: Adele Deutsch (m. 1887–1899), Angelika Dittrich (m. 1878–1882), Henrietta Treffz (m. 1862–1878)

Early Life

Austrian composer Johann Strauss Jr. was born into a Catholic family in St Ulrich near Vienna (now a part of Neubau), Austria, on 25 October 1825, to the composer Johann Strauss I. He was known for his waltzes (dances) and operettas (light operas with songs and dances). His music seems to capture the height of elegance and refinement of the Hapsburg regime.

His father, Johann Strauss the Elder, was a self-taught musician who established a musical dynasty in Vienna, writing waltzes, galops, polkas and quadrilles and publishing more than 250 works. Strauss Jr. composed over 500 waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, and other types of dance music, as well as several operettas and a ballet. In his lifetime, he was known as “The Waltz King”, and was largely responsible for the popularity of the waltz in Vienna during the 19th century.

Strauss had two younger brothers, Josef and Eduard Strauss, who became composers of light music as well, although they were never as well known as their elder brother. Some of Johann Strauss’s most famous works include “The Blue Danube”, “Kaiser-Walzer” (Emperor Waltz), “Tales from the Vienna Woods”, and the “Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka”. Among his operettas, Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron are the best known.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Johann Strauss II, also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger, “the Waltz King,” a composer famous for his Viennese waltzes and operettas, was born on October 25, 1825, in Vienna, Austria. was the eldest son of the composer Johann Strauss the Elder. His paternal great-grandfather was a Hungarian Jew a fact which the Nazis, who lionised Strauss’s music as “so German”, later tried to conceal. His father did not want him to become a musician but rather a banker.

Although the name Strauss can be found in reference books frequently with “ß” (Strauß), Strauss himself wrote his name with a long “s” and a round “s” (Strauſs), which was a replacement form for the Fraktur-ß used in antique manuscripts. His family called him “Schani”, derived from the Italian “Gianni”, a diminutive of “Giovanni”, the Italian equivalent of “Johann” (John).

Strauss’s mother secretly encouraged the musical education of her son behind his father’s back. She arranged for one of the members of the father’s orchestra to give the younger Johann lessons without his father’s knowledge. When his father left the family in 1940, Strauss was relieved, for it meant that he could freely pursue his music without secrecy. At the age of nineteen, he organized his own small orchestra, which performed some of his compositions in a restaurant in Hietzing. When his father died in 1849, Strauss combined his band with his father’s and became the leader. He ultimately earned his own nickname, “the king of the waltz,” or “the waltz king.”

Nevertheless, Strauss Junior studied the violin secretly as a child with the first violinist of his father’s orchestra, Franz Amon. Strauss studied counterpoint and harmony with theorist Professor Joachim Hoffmann, who owned a private music school. His talents were also recognized by composer Joseph Drechsler, who taught him exercises in harmony. It was during that time that he composed his only sacred work, the graduale Tu qui regis totum orbem (1844).

Strauss’s other violin teacher, Anton Kollmann, who was the ballet répétiteur of the Vienna Court Opera, also wrote excellent testimonials for him. Armed with these, he approached the Viennese authorities to apply for a license to perform. He initially formed his small orchestra where he recruited his members at the Zur Stadt Belgrad tavern, where musicians seeking work could be hired easily

Personal Life

Johann Strauss Jr. married the singer Henrietta Treffz in 1862, and they remained together until her death in 1878. Six weeks after her death, Strauss married the actress Angelika Dittrich. Dittrich was not a fervent supporter of his music, and their differences in status and opinion, and especially her indiscretion, led him to seek a divorce.

He was not granted a divorce by the Roman Catholic Church, and therefore changed religion and nationality, and became a citizen of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in January 1887. Strauss sought solace in his third wife Adele Deutsch, whom he married in August 1887. She encouraged his creative talent to flow once more in his later years, resulting in many famous compositions, such as the operettas Der Zigeunerbaron and Waldmeister, and the waltzes “Kaiser-Walzer” Op. 437, “Kaiser Jubiläum” Op. 434, and “Klug Gretelein” Op. 462.

Career and Works

Johann Strauss Jr. studied the violin without his father’s knowledge, however, and in 1844 conducted his own dance band at a Viennese restaurant. In 1849, when the elder Strauss died, Johann combined his orchestra with his father’s and went on a tour that included Russia (1865–66) and England (1869), winning great popularity. In 1870 he relinquished leadership of his orchestra to his brothers, Josef and Eduard, in order to spend his time writing music. In 1872 he conducted concerts in New York City and Boston.

Strauss made his debut at Dommayer’s in October 1844, where he performed some of his first works, such as the waltzes “Sinngedichte”, Op. 1 and “Gunstwerber”, Op. 4 and the polka “Herzenslust”, Op. 3. Critics and the press were unanimous in their praise for Strauss’s music. A critic for Der Wanderer commented that “Strauss’s name will be worthily continued in his son; children and children’s children can look forward to the future, and three-quarter time will find a strong footing in him.”

Strauss began composing for the Vienna Men’s Choral Association in 1847. His father died two years later, prompting him to conflate his own and his father’s orchestras, after which he mounted a successful career. In 1853, Strauss fell ill, and his younger brother, Josef, took control of the orchestra for six months. After recovering, he dove back into conducting and composing activities a pursuit that proved to be stronger than ever, gaining the eventual attention of such luminaries as Verdi, Brahms, and Wagner.

Strauss toured throughout Europe and England with great success and also went to America. He conducted huge concerts in Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City. He was the official conductor of the court balls in Vienna from 1863 to 1870. During this time he composed his most famous waltzes, including On the Beautiful Blue Danube (1867), probably the best-known waltz ever written, Artist’s Life (1867), Tales from the Vienna Woods (1868), and Wine, Women, and Song (1869).

Strauss also composed a number of patriotic marches dedicated to the Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef I, such as the “Kaiser Franz-Josef Marsch” Op. 67 and the “Kaiser Franz Josef Rettungs Jubel-Marsch” Op. 126, probably to ingratiate himself in the eyes of the new monarch, who ascended to the Austrian throne after the 1848 revolution.

In 1863 Jacques Offenbach (1819–1880), Paris’s most popular composer of light operas visited Vienna. The two composers met. The success of Offenbach’s stage works encouraged Strauss to try writing operettas. He resigned as court conductor in 1870 to devote himself to this pursuit.

Strauss’s most famous single composition is An der schönen blauen Donau (1867; The Blue Danube), the main theme of which became one of the best-known tunes in 19th-century music. His many other melodious and successful waltzes include Morgenblätter (1864; Morning Papers), Künstlerleben (1867; Artist’s Life), Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald (1868; Tales from the Vienna Woods), Wein, Weib und Gesang (1869; Wine, Women and Song), Wiener Blut (1871; Vienna Blood), and Kaiserwaltzer (1888). Of his nearly 500 dance pieces, more than 150 were waltzes.

Strauss Jr. eventually attained greater fame than his father and became one of the most popular waltz composers of the era, extensively touring Austria, Poland, and Germany with his orchestra. He applied for the KK Hofballmusikdirektor (Music Director of the Royal Court Balls) position, which he finally attained in 1863, after being denied several times before for his frequent brushes with the local authorities. In the 1870s, Strauss and his orchestra toured the United States, where he took part in the Boston Festival at the invitation of bandmaster Patrick Gilmore and was the lead conductor in a “Monster Concert” of over 1000 performers, performing his “Blue Danube” waltz, amongst other pieces, to great acclaim.

Among his stage works, Die Fledermaus (1874; The Bat) became the classical example of Viennese operetta. Equally successful was Der Zigeunerbaron (1885; The Gypsy Baron). Among his numerous other operettas are Der Karneval in Rom (1873; The Roman Carnival) and Eine Nacht in Venedig (1883; A Night in Venice).

On the heels of his American tour and his international rise, Strauss encountered his share of loss in the 1870s: His mother and brother Josef died around the same time, and his wife died of a heart attack in 1878. Strauss married two more times and remained productive right up until his final days.

Strauss continued to compose dance music, including the famous waltzes Roses from the South (1880) and Voices of Spring (1883). This last work, most often heard today as a purely instrumental composition, was originally conceived with a soprano solo as the composer’s only independent vocal waltz.

The most famous of Strauss’s operettas are Die Fledermaus, Eine Nacht in Venedig, and Der Zigeunerbaron. There are many dance pieces drawn from themes of his operettas, such as “Cagliostro-Walzer” Op. 370 (from Cagliostro in Wien), “O Schöner Mai” Walzer Op. 375 (from Prinz Methusalem), “Rosen aus dem Süden” Walzer Op. 388 (from Das Spitzentuch der Königin), and “Kuss-Walzer” op. 400 (from Der Lustige Krieg), that have survived obscurity and become well-known. Strauss also wrote an opera, Ritter Pázmán, and was in the middle of composing a ballet, Aschenbrödel, when he died in 1899.

Awards and Honor

Two museums in Vienna are dedicated to Johann Strauss II. His residence in the Praterstrasse where he lived in the 1860s is now part of the Vienna Museum. The Strauss Museum is about the whole family with a focus on Johann Strauss II.

Death and Legacy

Johann Strauss Jr. was diagnosed with pleuropneumonia, and on 3 June 1899, he died in Vienna, at the age of 73. He was buried in the Zentralfriedhof. At the time of his death, he was still composing his ballet Aschenbrödel.

Three operettas are consistently popular and available for performance today. The finest of them, Die Fledermaus (1874; The Bat), is probably one of the greatest operettas ever written and a masterpiece of its kind. The lovely Du und Du waltz is made up of excerpts from this work. His two other most successful operettas were A Night in Venice (1883), from which he derived the music for the Lagoon Waltz, and The Gypsy Baron (1885), from which stems the Treasure Waltz.

Most of the Strauss works that are performed today may once have existed in a slightly different form, as Eduard Strauss destroyed much of the original Strauss orchestral archives in a furnace factory in Vienna’s Mariahilf district in 1907. Eduard, then the only surviving brother of the three, took this drastic precaution after agreeing to a pact between himself and brother Josef that whoever outlived the other was to destroy their works. The measure was intended to prevent the Strauss family’s works from being claimed by another composer. This may also have been fueled by Strauss’s rivalry with another of Vienna’s popular waltz and march composers, Karl Michael Ziehrer.

Strauss wrote more than 150 waltzes, one hundred polkas, seventy quadrilles (square dances), mazurkas (folk dances from Poland), marches, and galops (French dances). His music combines considerable melodic invention, tremendous energy, and brilliance with suavity and polish, and even at times an incredibly refined sensuality. He refined the waltz and raised it from its beginnings in the common beer halls and restaurants to a permanent place in aristocratic (having to do with the upper-class) ballrooms.

The lives of the Strauss dynasty members and their world-renowned craft of composing Viennese waltzes are also briefly documented in several television adaptations, such as The Strauss Family (1972), The Strauss Dynasty (1991) and Strauss, the King of 3/4 Time (1995). Many other films used his works and melodies, and several films have been based upon the life of the musician, the most famous of which is called The Great Waltz (1938), redone in 1972. After a trip to Vienna, Walt Disney was inspired to create four feature films. One of those was The Waltz King, a loosely adapted biopic of Strauss, which aired as part of the Wonderful World of Disney in the U.S. in 1963. In Mikhail Bulgakov’s 1940 (published 1967) novel, The Master and Margarita, Strauss conducts the orchestra during Satan’s Great Ball at the invitation of Behemoth.

Information Source: