Biography of Chien-Shiung Wu

Chien-Shiung Wu – Chinese-American experimental physicist.

Name: Chien-Shiung Wu

Date of Birth: May 31, 1912

Place of Birth: Liuhe, Taicang, Jiangsu, China

Date of Death: February 16, 1997 (aged 84)

Place of Death: New York City, United States

Spouse/Ex: Luke Chia-Liu Yuan (m. 1942)

Children: Vincent Yuan (袁緯承)

Early Life

Chinese-American nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu on May 31st, 1912, in the town of Liuhe in Taicang, Jiangsu province, China. She is also known as “the First Lady of Physics,” contributed to the Manhattan Project and made history with an experiment that disproved the hypothetical law of conservation of parity.

She was a Chinese-American experimental physicist who made significant contributions in the field of nuclear physics. Wu worked on the Manhattan Project, where she helped develop the process for separating uranium metal into uranium-235 and uranium-238 isotopes by gaseous diffusion. She is best known for conducting the Wu experiment, which contradicted the hypothetical law of conservation of parity. This discovery resulted in her colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang winning the 1957 Nobel Prize in physics and earned Wu the inaugural Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978. Her expertise in experimental physics evoked comparisons to Marie Curie.

She has been dubbed “the First Lady of Physics,” “Queen of Nuclear Research,” and “the Chinese Madame Curie.” Her research contributions include work on the Manhattan Project and the Wu experiment, “which contradicted the hypothetical law of conservation of parity.” Her book Beta Decay (1965) is still a standard reference for nuclear physicists.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Chien-Shiung Wu was born on May 29, 1912, Liuhe, Jiangsu province, China, at the second of three children of Wu Zhong-Yi (吳仲裔) and Fan Fu-Hua. The family custom was that children of this generation had Chien as the first character (generation name) of their forename, followed by the characters in the phrase Ying-Shiung-Hao-Jie, which means “heroes and outstanding figures”. Accordingly, she had an older brother, Chien-Ying, and a younger brother, Chien-Hao. Wu and her father were extremely close, and he encouraged her interests passionately, creating an environment where she was surrounded by books, magazines, and newspapers.

Her mother, a teacher, and her father, an engineer, encouraged her to pursue science and mathematics from an early age. Wu received her elementary school education at Ming De School, a school for girls founded by her father. She left her hometown in 1923 at the age of 11 to go to the Suzhou Women’s Normal School No. 2. This was a boarding school with classes for teacher training as well as for regular high school. Admission to teacher training was more competitive, as it did not charge for tuition or board and guaranteed a job on graduation. Although her family could have afforded to pay, Wu chose the more competitive option and was ranked ninth among around 10,000 applicants.

In 1926, Wu joined the National Central University in mainland China. In 1930, Wu enrolled in one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions of higher learning in China, Nanjing (or Nanking) University, also known as National Central University, where she first pursued mathematics but quickly switched her major to physics, inspired by Marie Curie. She graduated with top honors at the head of her class with a B.S. degree in 1934.

For two years after graduation, Wu did a graduate-level study in physics and worked as an assistant at Zhejiang University. She became a researcher at the Institute of Physics of the Academia Sinica. Her supervisor was Gu Jing-Wei, who had earned her Ph.D. abroad at the University of Michigan and encouraged Wu to do the same. Wu was accepted by the University of Michigan, and her uncle, Wu Zhou-Zhi, provided the necessary funds. She embarked for the United States with a female friend, Dong Ruo-Fen (董若芬), a chemist from Taicang, on the SS President Hoover in August 1936. Her parents and uncle saw her off. She would never see her parents again.

Wu then traveled to the United States to pursue graduate studies in physics at the University of California at Berkeley, studying under Ernest O. Lawrence. After receiving a Ph.D. in 1940, she taught at Smith College and at Princeton University. In 1944 she undertook work on radiation detection in the Division of War Research at Columbia University. Remaining on the university staff at Columbia after the war, she became Dupin professor of physics there in 1957.

Personal Life

Chien-Shiung Wu married a fellow former graduate student, Luke Chia-Liu Yuan on May 30, 1942, and the two moved to the East coast where Yuan worked at Princeton University and Wu worked at Smith College.

In 1947 the couple welcomed a son, Vincent Wei-Cheng Yuan, to their family. Vincent would go on to follow in Wu’s footsteps and also became a nuclear scientist.

Career and Works

After graduation, Wu taught for a year at the National Chekiang (Zhejiang) University in Hangzhou and worked in a physics laboratory at the Academia Sinica where she conducted her first experimental research in X-ray crystallography (1935-1936) under the mentorship of Jing-Wei Gu, a female professor. Dr. Gu encouraged her to pursue graduate studies in the United States and in 1936, she visited the University of California at Berkeley. It was there she met Professor Ernest Lawrence, who was responsible for the first cyclotron and who later won a Nobel Prize, and another Chinese physics student, Luke Chia-Yuan, who influenced her both to remain at Berkeley and obtain her Ph.D. Wu’s graduate work focused on a highly desirable topic of that era: uranium fission products.

Arrived in San Francisco, where Wu’s plans for graduate study changed after visiting the University of California, Berkeley. She met physicist Luke Chia-Liu Yuan, a grandson of Yuan Shikai (the first President of the Republic of China and self-proclaimed Emperor of China). Yuan showed her the Radiation Laboratory, where the director was Ernest O. Lawrence, who would soon win the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron particle accelerator.

Wu made rapid progress in her education and her research. Although Lawrence was officially her supervisor, she also worked closely with Emilio Segrè. Her thesis had two separate parts. The first was on bremsstrahlung, the electromagnetic radiation produced by the deceleration of a charged particle when deflected by another charged particle, typically an electron by an atomic nucleus. She investigated this using beta-emitting phosphorus-32, a radioactive isotope easily produced in the cyclotron that Lawrence and his brother John H. Lawrence were evaluating for use in cancer treatment and as a radioactive tracer. This marked Wu’s first work with beta decay, a subject on which she would become an authority. The second part of the thesis was about the production of radioactive isotopes of xenon produced by the nuclear fission of uranium with the 37-inch and 60-inch cyclotrons at the Radiation Laboratory.

She completed her Ph.D. in June 1940 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. In spite of Lawrence and Segrè’s recommendations, she could not secure a position at a university, so she remained at the Radiation Laboratory as a post-doctoral fellow.

Wu joined the Manhattan project early in WWII. Here she helped develop the process to enrich uranium ore to produce the fuel for the atomic bomb. In 1944 she accepted a position at Columbia University where she did some research. Her research at the university helped to disprove the law of conservation of parity. This law has been assumed to be a fundamental law of nature. It stated that beta particles emitted by a radioactive nucleus would fly off in any given direction, regardless of the spin of the nucleus.

In September 1944, Wu was contacted by the Manhattan District Engineer, Colonel Kenneth Nichols. The newly commissioned B Reactor at the Hanford Site had run into an unexpected problem, starting up and shutting down at regular intervals. John Archibald Wheeler suspected that a fission product, xenon-135, with a half-life of 9.4 hours, was the culprit, and might be a neutron poison. Segrè then remembered the work that Wu had done at Berkeley on the radioactive isotopes of xenon. The paper on the subject was still unpublished, but Wu and Nichols went to her dorm room and collected the typewritten draft prepared for the Physical Review. Xenon-135 was indeed the culprit; it turned out to have an unexpectedly large neutron absorption cross-section.

She also discovered a way “to enrich uranium ore that produced large quantities of uranium as fuel for the bomb.”

After leaving the Manhattan Project in 1945, Wu spent the rest of her career in the Department of Physics at Columbia as the undisputed leading experimentalist in beta decay and weak interaction physics. After being approached by two male theoretical physicists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang, “Wu’s experiments using cobalt-60, a radioactive form of the cobalt metal” disproved “the law of parity (the quantum mechanics law that held that two physical systems, such as atoms, are mirror images that behave in identical ways).”

In 1949, Yuan joined the Brookhaven National Laboratory, and the family moved to Long Island. After the communists came to power in China that year, Wu’s father wrote urging her not to return. Since her passport had been issued by the Kuomintang government, she found it difficult to travel abroad. This eventually led to her decision to become a US citizen in 1954. She would remain at Columbia for the rest of her career. She became an associate professor in 1952, a full professor in 1958, and the Michael I. Pupin Professor of Physics in 1973. Her students called her the Dragon Lady, after the character of that name in the comic strip Terry and the Pirates.

In 1956 Tsung-Dao Lee of Columbia and Chen Ning Yang of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey, proposed that parity is not conserved for weak nuclear interactions. With a group of scientists from the National Bureau of Standards, Washington, D.C., Wu that year tested the proposal by observing the beta particles given off by cobalt-60. Wu observed that there is a preferred direction of emission and that, therefore, parity is not conserved for this weak interaction. She announced her results in 1957.

Unfortunately, although this led to a Nobel Prize for Yang and Lee in 1957, Wu was excluded, as were many other female scientists during this time. Wu was aware of gender-based injustice and at an MIT symposium in October of 1964, she stated:

“I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

In 1958 Richard P. Feynman and Murray Gell-Mann proposed the conservation of vector current in nuclear beta decay. This theory was experimentally confirmed in 1963 by Wu in collaboration with two other Columbia University research physicists. She later investigated the structure of hemoglobin.

At Columbia, Wu knew the Chinese-born theoretical physicist Tsung-Dao Lee personally. In the mid-1950s, Lee and another Chinese theoretical physicist, Chen Ning Yang, grew to question a hypothetical law of elementary particle physics, the “law of conservation of parity”. One example highlighting the problem was the puzzle of the theta and tau particles, two apparently different charged, strange mesons. They were so similar that they would ordinarily be considered to be the same particle; but different decay modes resulting in two different parity states were observed, suggesting that

Θ+ and T+ were different particles if parity is conserved:

Θ+ → π+ + π0

Τ+ → π+ + π+ + π−

Lee and Yang’s research into existing experimental results convinced them that parity was conserved for electromagnetic interactions and for the strong interaction. For this reason, scientists had expected that it would also be true for the weak interaction, but it had not been tested, and Lee and Yang’s theoretical studies showed that it might not hold true for the weak interaction. Lee and Yang worked out a pencil-and-paper design of an experiment for testing the conservation of parity in the laboratory. Lee then turned to Wu for her expertise in choosing and then working out the hardware manufacturer, set-up, and laboratory procedures for carrying out this experiment.

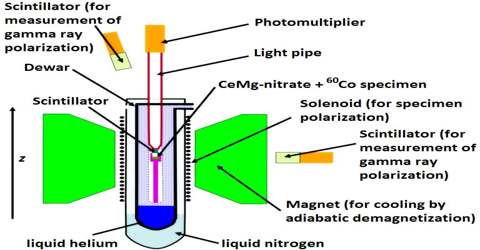

(Schematic illustration of the Wu experiment)

In 1957, utilizing atoms of cobalt-60, Wu showed that beta particles were most likely to be emitted in a particular direction. This direction depended on the spin of the cobalt nuclei. This confirmed a 1956 theory by other scientists who received the 1957 Nobel Prize in physics. Wu’s role in the discovery was not publicly honored until 1978 when she was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize. Wu also conducted research on molecular changes in the deformation of hemoglobin that lead to sickle-cell anemia.

After being promoted to Associate (1952) and then to Full Professor (1958) and becoming the first woman to hold a tenured faculty position in the physics department at Columbia, she was appointed the first Michael I. Pupin Professor of Physics in 1973.

In later life, Wu became more outspoken. She protested the imprisonment in Taiwan of relatives of physicist Kerson Huang in 1959 and of the journalist Lei Chen in 1960. In 1964, she spoke out against gender discrimination at a symposium at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “I wonder,” she asked her audience, “whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.” When men referred to her as Professor Yuan, she immediately corrected them and told them that she was Professor Wu. In 1975, Robert Serber, the new chairman of the Physics Department at Columbia University, adjusted her pay to make it equal to that of her male counterparts. She protested the crackdown in China that followed the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989.

Wu retired from Columbia in 1981 and devoted her time to educational programs in the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, and the United States. She was a huge advocate for promoting girls in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and lectured widely to support this cause becoming a role model for young women scientists everywhere.

Awards and Honor

In 1958, Wu was the first woman to earn the Research Corporation Award and the seventh woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences. She also received the National Academy of Sciences Cyrus B. Comstock Award in Physics (first woman to receive this award, 1964), the Bonner Prize (1975), and the Wolf Prize in Physics (inaugural award, 1978). She was the first woman to receive an Sc.D. from Princeton University (1958) and was awarded many honorary degrees.

Wu also received the National Medal of Science in the year 1975 and the John Price Wetherill Medal at the Franklin Institute in 1962.

Death and Legacy

Chien-Shiung Wu died on February 16, 1997, in New York City at the age of 84 after suffering a stroke. An ambulance rushed her to St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital Center, but she was pronounced dead on arrival. She was survived by her husband and son. In accordance with her wishes, her ashes were buried in the courtyard of the Ming De School that her father had founded and she had attended as a girl.

Devoted to science, Wu mentored and encouraged not only her son but dozens of graduate students throughout her career. She is remembered as a trailblazer in the scientific community and an inspirational role model. Her granddaughter, Jada Wu Hanjie, remarked “I was young when I saw my grandmother, but her modesty, rigorousness and beauty were rooted in my mind. My grandmother had emphasized much enthusiasm for national scientific development and education, which I really admire.”

In 1974 Wu was named Scientist of the Year by Industrial Research Magazine and in 1976, she was the first woman to serve as president of the American Physical Society. In 1990 the Chinese Academy of Sciences named Asteroid 2752 after her (she was the first living scientist to receive this honor) and five years later, Tsung-Dao Lee, Chen Ning Yang, Samuel C. C. Ting, and Yuan T. Lee founded the Wu Chien-Shiung Education Foundation in Taiwan for the purposes of providing scholarships to young aspiring scientists.

In 1998 Wu was inducted into the American National Women’s Hall of Fame a year after her death.

Information Source: