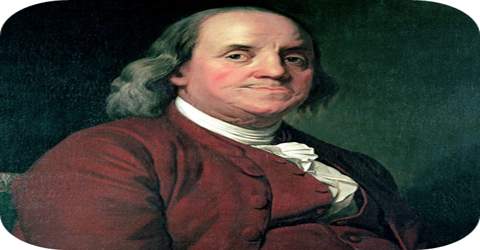

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

(Author, Printer, Politician, Freemason, Postmaster, Scientist, Inventor, Civic Activist, Statesman, and Diplomat)

Date of Birth: January 17, 1706

Place of birth: Boston, Massachusetts Bay, British America

Date of Death: April 17, 1790 (aged 84)

Place of death: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Cause of death: Pleurisy

Political party: Independent

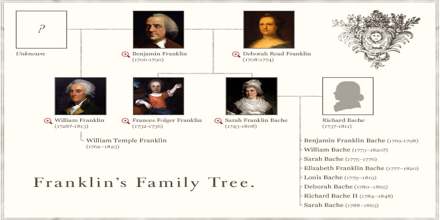

Spouse(s): Deborah Read (m. 1730–1774)

Children: William Franklin, Sarah Franklin Bache, Francis Folger Franklin

Early Life

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston in what was then known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was a renowned polymath and a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, freemason, postmaster, scientist, inventor, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. As an inventor, he is known for the lightning rod, bifocals, and the Franklin stove, among other inventions. He facilitated many civic organizations, including Philadelphia’s fire department and The University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League institution.

He has often been referred to as ‘America’s Renaissance Man’ and was emblematic of the fledgling American nation.

Franklin was foundational in defining the American ethos as a marriage of the practical values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit, self-governing institutions, and opposition to authoritarianism both political and religious, with the scientific and tolerant values of the Enlightenment. In the words of historian Henry Steele Commager, “In a Franklin could be merged the virtues of Puritanism without its defects, the illumination of the Enlightenment without its heat.” To Walter Isaacson, this makes Franklin “the most accomplished American of his age and the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become.”

By the age of just 23, Franklin had become the publisher of the Philadelphia Gazette.

Aged 27, in December 1732, the first editions of the publication that would make him a wealthy man rolled off his printing press: Poor Richard’s Almanac, which Franklin would publish annually for the next 25 years. It was a general interest pamphlet offering interest and amusement for its readers, including: ‘how to’ guides, practical tips, stories, astrological forecasts, and brain teasers.

With each year he published the Almanac, his financial position grew more secure, and Franklin’s fertile mind began looking for new outlets.

He continued reading as much as he could, increasing his knowledge of science and technology until he was in a position to begin innovating himself.

He pioneered and was first president of The Academy and College of Philadelphia which opened in 1751 and later became the University of Pennsylvania. He organized and was the first secretary of the American Philosophical Society and was elected president in 1769. Franklin became a national hero in America as an agent for several colonies when he spearheaded an effort in London to have the Parliament of Great Britain repeal the unpopular Stamp Act. An accomplished diplomat, he was widely admired among the French as American minister to Paris and was a major figure in the development of positive Franco-American relations. His efforts proved vital for the American Revolution in securing shipments of crucial munitions from France.

He was promoted to deputy postmaster-general for the British colonies in 1753, having been Philadelphia postmaster for many years, and this enabled him to set up the first national communications network. During the Revolution, he became the first US Postmaster General.

His colorful life and legacy of scientific and political achievement, and his status as one of America’s most influential Founding Fathers have seen Franklin honored more than two centuries after his death on coinage and the $100 bill, warships, and the names of many towns, counties, educational institutions, and corporations, as well as countless cultural references.

Franklin lived in turbulent times, which culminated in the United States’ Declaration of Independence in 1776: Franklin was one of the five men who drafted it. He had previously acted as British postmaster for the colonies; he was the American Ambassador in France from 1776 – 1785; and the governor of Pennsylvania from 1785 – 1788.

Childhood and Educational Life

Ben learned to read at an early age, and despite his success at the Boston Latin School, he stopped his formal schooling at 10 to work full-time in his cash-strapped father’s candle and soap shop. Dipping wax and cutting wicks didn’t fire the young boy’s imagination, however. Perhaps to dissuade him from going to sea as one of his brothers had done, Josiah apprenticed Ben at 12 to his brother James at his print shop. When Ben was 15, James founded The New-England Courant, which was the first truly independent newspaper in the colonies.

At an early age, he also started writing articles which were published in the New England Coureant under a pseudonym; Franklin wrote under pseudonym’s throughout his life. After several were published, he admitted to his father that he had wrote them. Rather than being pleased his father beat him for his impudence. Therefore, aged 17, the young Benjamin left the family business and travelled to Philadelphia.

Personal Life

Benjamin Franklin was born January 17, 1706 into a large and poor family. His father had 17 children by two different wives. Ben was his 15th child and youngest son. Benjamin was brought up in the family business of candle making and his brother’s printing shop.

When he was twelve, Benjamin began working as an apprentice in a printing shop owned by one of his elder brothers, James. When his brother started printing a newspaper, Benjamin wrote to it in the name of “Mrs. Dogood” in defense of freedom of speech.

Franklin’s father, Josiah Franklin was a tallow chandler, a soap-maker and a candle-maker. Josiah was born at Ecton, Northamptonshire, England on December 23, 1657, the son of Thomas Franklin, a blacksmith-farmer, and Jane White. His mother, Abiah Folger, was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts, on August 15, 1667, to Peter Folger, a miller and schoolteacher and his wife Mary Morrill, a former indentured servant.

After the future Founding Father rekindled his romance with Deborah Read, he took her as his common-law wife in 1730. They took in Franklin’s recently acknowledged young illegitimate son William and raised him in their household. They had two children together. Their son, Francis Folger Franklin, was born in October 1732 and died of smallpox in 1736. Their daughter, Sarah “Sally” Franklin, was born in 1743 and grew up to marry Richard Bache, have seven children, and look after her father in his old age.

Deborah Read Franklin died of a stroke in 1774, while Franklin was on an extended mission to England; he returned in 1775.

Publishing Career

By the age of just 23, Franklin had become the publisher of the Philadelphia Gazette.

In Philadelphia, Benjamin’s reputation as an acerbic man of letters grew. His writings were both humorous and satirical, but they also raised the fears of the Pennsylvania governor, William Keith. William Keith was fearful of Benjamin’s talents so offered him a job in England with all expenses paid. Benjamin took the offer, but once in England the governor deserted Franklin, leaving him with no funds.

Aged 27, in December 1732, the first editions of the publication that would make him a wealthy man rolled off his printing press: Poor Richard’s Almanac, which Franklin would publish annually for the next 25 years. It was a general interest pamphlet offering interest and amusement for its readers, including: ‘how to’ guides, practical tips, stories, astrological forecasts, and brain teasers.

With each year he published the Almanac, his financial position grew more secure, and Franklin’s fertile mind began looking for new outlets.

He continued reading as much as he could, increasing his knowledge of science and technology until he was in a position to begin innovating himself.

In 1733, Franklin began to publish the noted Poor Richard’s Almanack (with content both original and borrowed) under the pseudonym Richard Saunders, on which much of his popular reputation is based. Franklin frequently wrote under pseudonyms. Although it was no secret that Franklin was the author, his Richard Saunders character repeatedly denied it. “Poor Richard’s Proverbs”, adages from this almanac, such as “A penny saved is twopence dear” (often misquoted as “A penny saved is a penny earned”) and “Fish and visitors stink in three days”, remain common quotations in the modern world. Wisdom in folk society meant the ability to provide an apt adage for any occasion, and Franklin’s readers became well prepared. He sold about ten thousand copies per year—it became an institution. In 1741 Franklin began publishing The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle for all the British Plantations in America, the first such monthly magazine of this type published in America.

Science, Innovation, and Inventions Career

He felt limited by the spectacles of his day, because a lens that was good for reading blurred his vision when he looked up. Working as a printer, this could be infuriating.

He defeated this problem in about 1739, aged 33, with his invention of split-lens bifocal spectacles. Each lens now had two focusing distances. Looking through the bottom part of the lens was good for reading, while looking through the upper part offered good vision at a greater distance.

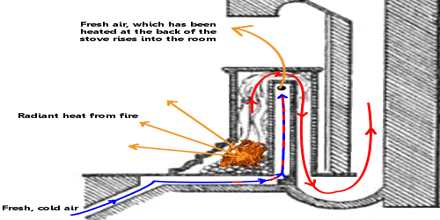

As Franklin read more about science, he learned more about heat transfer. He looked at the design of a typical stove and concluded that it was inefficient. Much more heat was lost up the flue than necessary.

He decided to redesign the stove using the concept of heat-exchange/heat recovery.

The idea was that hot gases which would normally simply go up the flue would exchange their heat with cold air from the room, heating it up, and so heating the room up.

In 1741, the Franklin Stove came on to the market, allowing homeowners to get more heat into their homes for each unit of fuel they burned.

Franklin started exploring the phenomenon of electricity in 1746 when he heard of the Leyden jar. Franklin proposed that “vitreous” and “resinous” electricity were not different types of “electrical fluid” (as electricity was called then), but the same “fluid” under different pressures. He was the first to label them as positive and negative respectively, and he was the first to discover the principle of conservation of charge. In 1748 he constructed a multiple plate capacitor, that he called an “electrical battery” (not to be confused with Volta’s pile) by placing eleven panes of glass sandwiched between lead plates, suspended with silk cords and connected by wires.

Franklin had an idea for an experiment to prove that lightning is electricity, making use of another of his own discoveries in electricity: that static electricity discharges to a sharp, pointed object more readily than to a blunt object.

In recognition of his work with electricity, Franklin received the Royal Society’s Copley Medal in 1753, and in 1756 he became one of the few 18th-century Americans elected as a Fellow of the Society. He received honorary degrees from Harvard and Yale universities (his first). The cgs unit of electric charge has been named after him: one franklin (Fr) is equal to one statcoulomb.

Franklin advised Harvard University in its acquisition of new electrical laboratory apparatus after the complete loss of its original collection, in a fire which destroyed the original Harvard Hall in 1764. The collection he assembled would later become part of the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, now on public display in its Science Center.

In 1758, working with John Hadley in Cambridge, England, Franklin investigated the principle of refrigeration by evaporation.

In a room at 18 °C (65 °F), the scientists repeatedly wetted a thermometer with ether, then used bellows to quickly evaporate the ether.

They were finally able to achieve a temperature reading on the thermometer of -14 °C (7 °F).

We now know the reason for the refrigeration effect. We have learned that molecules in a liquid have a range of energies. Some have high energy, and some have low energy. Molecules carrying the most energy escape from the liquid most easily – they evaporate. This leaves the lower energy, colder molecules in the liquid. The result is that the temperature of the liquid falls.

In fact, the principle of cooling by evaporation had been publicly demonstrated by William Cullen in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1756. Cullen had used a pump to lower the pressure above ether in a container.

The reduced pressure caused the ether to evaporate rapidly through boiling, absorbing heat from the air around it, and causing some ice to form on the container sides.

By observation of storms and winds, Franklin discovered that storms do not always travel in the direction of the prevailing wind. This was an important discovery in the development of the scientific discipline of meteorology.

While traveling on a ship, Franklin had observed that the wake of a ship was diminished when the cooks scuttled their greasy water. He studied the effects on a large pond in Clapham Common, London. “I fetched out a cruet of oil and dropt a little of it on the water … though not more than a teaspoon full, produced an instant calm over a space of several yards square.” He later used the trick to “calm the waters” by carrying “a little oil in the hollow joint of my cane”.

Professional Career

Franklin served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and then as one of the aspiring republic’s most important diplomats abroad. He also aided in the drafting of the Constitution towards the end of his life.

Franklin’s first job was as an assistant to his father’s candle-making business, a task which seems to have bored him. Franklin then moved into the printing business, first working under his brother and then plying the trade in Philadelphia. Franklin’s work as an inventor rested mainly in electrical theory, a passion perhaps best exemplified by his famous kite experiment. Additionally, Franklin tried his hand at entrepreneurship with the development of the Franklin stove. Throughout his adult life, Franklin was busy writing letters, pamphlets and other literature, some of the most notable being his infamous “Silence Dogood” letters and the financially lucrative “Poor Richard’s Almanac.”

In the 1730’s, Franklin’s wealth and prestige increased due to the addition of several real estate ventures and his appointment to the Pennsylvania state assembly and the position of postmaster general of Philadelphia. At the outset of the Revolution, Franklin was a key figure in the Continental Congress, pushing for the independence agenda and helping to draft the Declaration of Independence itself. During the war, Franklin was the fledgling United States’ key ambassador to France and was instrumental in securing its financial and military intervention in support of the American cause. After the war, Franklin was also a leading delegate to the Constitutional Convention, the entity that ultimately produced the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Franklin was busy to the end of his life writing, seeing former colleagues and serving the abolitionist cause in Philadelphia.

Political Career

Franklin became a member of Philadelphia’s city council in 1748 and a justice of the peace the following year. In 1751 Franklin was elected a Philadelphia alderman and a representative to the Pennsylvania Assembly, a position to which he was re-elected annually until 1764. Two years later, he accepted a royal appointment as deputy postmaster general of North America.

When the French and Indian War began in 1754, Franklin called on the colonies to band together for their common defense, which he dramatized in The Pennsylvania Gazette with a cartoon of a snake cut into sections with the caption “Join or Die.” He represented Pennsylvania at the Albany Congress, which adopted his proposal to create a unified government for the 13 colonies. Franklin’s “Plan of Union,” however, failed to be ratified by the colonies.

In 1757 he was appointed by the Pennsylvania Assembly to serve as the colony’s agent in England. Franklin sailed to London to negotiate a long-standing dispute with the proprietors of the colony, the Penn family, taking William and his two slaves but leaving behind Deborah and Sarah. He spent most of the next two decades in London, where he was drawn to the high society and intellectual salons of the cosmopolitan city.

After Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1762, he toured the colonies to inspect its post offices and William took office as New Jersey’s royal governor, a position his father arranged through his political connections in the British government. After Franklin lost his seat in the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1764, he returned to London as the colony’s agent without Deborah, who refused to leave Philadelphia. It would be the last time the couple saw each other. Franklin would not return home before Deborah passed away in 1774 from a stroke at the age of 66.

In 1775, Franklin was elected to the Second Continental Congress and appointed the first postmaster general for the colonies. And in 1776, he was appointed commissioner to Canada and was one of five men to draft the Declaration of Independence. Franklin’s support for the patriot cause put him at odds with his Loyalist son. When the New Jersey militia stripped William Franklin of his post as royal governor and imprisoned him, his father chose not to intercede on his behalf. After voting for independence, Franklin was elected commissioner to France and set sail to negotiate a treaty for the country’s military and financial support.

Death

Benjamin Franklin died on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the home of his daughter, Sarah Bache. He was 84, suffered from gout and had complained of ailments for some time, completing the final codicil to his will a little more than a year and a half prior to his death.

(The grave of Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

(The grave of Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

Approximately 20,000 people attended his funeral. He was interred in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.

Franklin’s actual grave, however, as he specified in his final will, simply reads “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin”.

Honours

Today, the Benjamin Franklin Medal, named in Franklin’s honor, is one of the most prestigious awards in science. Its winners include Alexander Graham Bell, Marie and Pierre Curie, Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

Franklin appeared on the first U.S. postage stamp (displayed above) issued in 1847. From 1908 through 1923 the U.S. Post Office issued a series of postage stamps commonly referred to as the Washington-Franklin Issues where, along with George Washington, Franklin was depicted many times over a 14-year period, the longest run of any one series in U.S. postal history.

As a founding father of the United States, Franklin’s name has been attached to many things. Among these are:

- The State of Franklin, a short-lived independent state formed during the American Revolutionary War

- Counties in at least 16 U.S. states

- Several major landmarks in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Franklin’s longtime home, including:

- Franklin and Marshall College in nearby Lancaster

- Franklin Field, a football field once home to the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League and the home field of the University of Pennsylvania Quakers since 1895

- The Franklin Mercantile Chess Club in Philadelphia, the second oldest chess club in the U.S. (Franklin was a keen chess enthusiast and the first writer on chess in America)

- The Benjamin Franklin Bridge across the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey

- The Franklin Institute, a science museum in Philadelphia, which presents the Benjamin Franklin Medal

- The Sons of Ben soccer supporters club for the Philadelphia Union

- Ben Franklin Stores chain of variety stores, with a key-and-spark logo

- Franklin Templeton Investments an investment firm whose New York Stock Exchange ticker abbreviation, BEN, is also in honor of Franklin

- The Ben Franklin effect from the field of psychology

- Benjamin Franklin Shibe, baseball executive and namesake of the longtime Philadelphia baseball stadium

- Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce, the fictional character from the M*A*S*H novels, film, and television program

- Benjamin Franklin Gates, Nicolas Cage’s character from the National Treasure films.

- Several US Navy ships have been named the USS Franklin or the USS Bonhomme Richard, the latter being a French translation of his penname “Poor Richard”. Two aircraft carriers, USS Franklin (CV-13) and USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) were simultaneously in commission and in operation during World War II, and Franklin therefore had the distinction of having two simultaneously operational US Navy warships named in his honor. The French ship Franklin (1797) was also named in Franklin’s honor.

- Franklinia alatamaha, commonly called the Franklin tree. It was named after him by his friends and fellow Philadelphians, botanists James and William Bartram.

- CMA CGM Benjamin Franklin, a Chinese-built French owned Explorer-class container ship