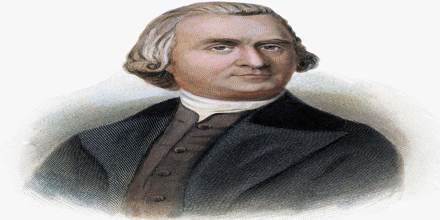

Samuel Adams (1722-1803)

(American Statesman, Political Philosopher, and One of the Founding Fathers of the United States.)

Full Name: Samuel Adams

Date of birth: September 27 (O.S. September 16) 1722

Place of birth: Boston, Massachusetts Bay

Date of death: October 2, 1803 (aged 81)

Place of death: Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

Spouse: Elizabeth Wells (m. 1764–1803), Elizabeth Checkley (m. 1749–1757)

Children: Samuel Adams, Hannah Adams

Political party: Democratic-Republican (1790s)

Early Life

Samuel Adams was born on September 27, 1722, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was an American statesman, political philosopher, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Being the second cousin of Former American President John Adams, Samuel was a natural statesman making a great impact in the birth of modern day United States. Samuel was a key figure who started out the revolutionary movement which later went on to become the American Revolution. Samuel Adams was the prominent figure who had first voiced his dissent and opposition (by being a part of a significant political movement) against the British Parliament’s efforts to tax the British American colonies without their consent. Samuel had inspired his fellow colonists to strive for independence much before the American Revolution had started out. Samuel became a controversial political figure according to some historians who rejected his political approach because of his propaganda style of opposition and his popular initiation of mob violence to achieve his goals. However Adams’ approaches had been accepted and appreciated greatly by many modern historians and scholars.

Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774, at which time Adams attended the Continental Congress in Philadelphia which was convened to coordinate a colonial response. He helped guide Congress towards issuing the Continental Association in 1774 and the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and he helped draft the Articles of Confederation and the Massachusetts Constitution. Adams returned to Massachusetts after the American Revolution, where he served in the state senate and was eventually elected governor.

Adams’s life was greatly affected by his father’s involvement in a banking controversy. In 1739, Massachusetts was facing a serious currency shortage, and Deacon Adams and the Boston Caucus created a “land bank” which issued paper money to borrowers who mortgaged their land as security. The land bank was generally supported by the citizenry and the popular party, which dominated the House of Representatives, the lower branch of the General Court. Opposition to the land bank came from the more aristocratic “court party”, who were supporters of the royal governor and controlled the Governor’s Council, the upper chamber of the General Court. The court party used its influence to have the British Parliament dissolve the land bank in 1741. Directors of the land bank, including Deacon Adams, became personally liable for the currency still in circulation, payable in silver and gold. Lawsuits over the bank persisted for years, even after Deacon Adams’s death, and the younger Samuel Adams often had to defend the family estate from seizure by the government. For Adams, these lawsuits “served as a constant personal reminder that Britain’s power over the colonies could be exercised in arbitrary and destructive ways”.

Childhood and Educational Life

Samuel Adams was born in Boston in the British colony of Massachusetts on September 16, 1722, an Old Style date that is sometimes converted to the New Style date of September 27. Samuel was born in a family of 12 children to parents who were strict Puritans and went to the Old South Congregational Church as members of the Church. Samuel’s family lived in a house on Purchase Street in Boston. Samuel being brought up in Puritan values he was proud of them and even implied them in his political career. Adams’s parents were devout Puritans and members of the Old South Congregational Church.

Samuel Adams went to Boston Latin School. He got enrolled to Harvard College in 1736. Adams’ parents wanted him to become a minister. But with time Adams grew more inclined to take up politics as his career interest. Adams graduated in 1740. He completed his Master’s Degree in 1743.

In his thesis, he argued that it was “lawful to resist the Supreme Magistrate, if the Commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved”, which indicated that his political views, like his father’s, were oriented towards colonial rights.

Young Adams faced his father’s death at a tender age which led him to manage his family’s estates. While doing this Samuel realised how vulnerable their position was in defending their family property from the clutches of government seizure. Adams’ family faced constant fear of Government’s ill motives which formed the base for Adam’s realization that British rule exercised their power on the American colonies in arbitrary and destructive ways.

Personal Life

In October 1749 Adams married his pastor’s daughter, Elizabeth Checkley with whom he had six children over a period of seven years, but only two lived to adulthood: Samuel (born 1751) and Hannah (born 1756). Adams was elected as the tax collector at the Boston Town Meeting in 1756. Elizabeth died in July 1757 leading Adams to get married again to Elizabeth Wells in 1764 with whom he had no children.

Political Career

A strong opponent of British taxation, Adams helped organize resistance in Boston to Britain’s Stamp Act of 1765. He also played a vital role in organizing the Boston Tea Party—an act of opposition to the Tea Act of 1773—among various other political efforts.

Deacon Adams (Father of Samuel Adams) became a leading figure in Boston politics through an organization that became known as the Boston Caucus, which promoted candidates who supported popular causes.

Like his father, Adams embarked on a political career with the support of the Boston Caucus. He was elected to his first political office in 1747, serving as one of the clerks of the Boston market. In 1756, the Boston Town Meeting elected him to the post of tax collector, which provided a small income. He often failed to collect taxes from his fellow citizens, which increased his popularity among those who did not pay, but left him liable for the shortage. By 1765, his account was more than £8,000 in arrears. The town meeting was on the verge of bankruptcy, and Adams was compelled to file suit against delinquent taxpayers, but many taxes went uncollected. In 1768, his political opponents used the situation to their advantage, obtaining a court judgment of £1,463 against him. Adams’s friends paid off some of the deficit, and the town meeting wrote off the remainder. By then, he had emerged as a leader of the popular party, and the embarrassing situation did not lessen his influence.

Samuel Adams had become an important political figure in Boston. After the British became victorious in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) Adams’ political significance grew. Britain found itself troubled with debts and was constantly in the lookout for new revenue sources and this is when British Empire decided to levy taxes on its colonies in British America.

Disputes over tax brought severe bitterness between Britain and America and there were massive disputes on the interpretations of the British Constitution British Parliament’s authoritarian politics in the colonies. With the infringing (colonial rights were deeply disturbed) Sugar Act of 1764 Adams rose against British Rule stating that the colonies were not under British Parliament so they were not liable to fall under British taxation. Adams further explained that tax could legally be levied by the colonial assemblies with represented colonists on the colonies. Boston Town Meeting was held for the election of its Massachusetts House representatives where Adams let out his taxation views in May 1764.

Adams also wrote a set of written instructions (Town Meeting handed out each colony representative with the written instructions) that bore his thoughts on the dangers of taxation without representation. With Boston Town Meeting approving Adams instructions on 24 May 1764, the instructions went on to become the first political body in America that went on record to state that Parliament could not constitutionally tax the colonists. The directives in the instruction also contained the first official recommendation that the colonies present a unified defence of their rights. Adams’ instruction were printed in newspapers and pamphlets with which Adams found himself in the right place to quickly associate with James Otis, Jr., a member of the Massachusetts House famous for his defence of colonial rights.

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act which required colonists to pay a new tax on most printed materials. News of the passage of the Stamp Act produced an uproar in the colonies.

The colonial response echoed Adams’s 1764 instructions. In June 1765, Otis called for a Stamp Act Congress to coordinate colonial resistance. The Virginia House of Burgesses passed a widely reprinted set of resolves against the Stamp Act that resembled Adams’s arguments against the Sugar Act. Adams argued that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional; he also believed that it would hurt the economy of the British Empire. He supported calls for a boycott of British goods to put pressure on Parliament to repeal the tax.

Scattered protests took place against the Stamp Act which included organized protests led by a group called the Loyal Nine, based in Boston, of which Adams was friendly with but not a member. On 14 August 1765 stamp distributor Andrew Oliver effigy was hanged in Boston and his home and office were destroyed. On 26 August 1765 lieutenant governor Thomas Hutchinson’s home was demolished by an angry crowd in a similar manner. Adams was greatly blamed for the series of violent events and agitations. This record was set right by historians in the 20th century as it was found to be not true.

In September 1765, Adams was once again appointed by the Boston Town Meeting to write the instructions for Boston’s delegation to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. As it turned out, he wrote his own instructions; on September 27, the town meeting selected him to replace the recently deceased Oxenbridge Thacher as one of Boston’s four representatives in the assembly. James Otis was attending the Stamp Act Congress in New York City, so Adams was the primary author of a series of House resolutions against the Stamp Act, which were more radical than those passed by the Stamp Act Congress. Adams was one of the first colonial leaders to argue that mankind possessed certain natural rights that governments could not violate.

The Act had been annulled and the news spread to Boston by 16 May 1766. Following the Massachusetts popular party gaining hold in the May 1766 elections Adams saw himself being elected to the House serving as a clerk.

In 1767 Townshend Acts was passed which levied taxes on goods getting imported to the colonies. The British government played their game slowly by levying low tax rates thus resistance to Townshend Acts was slow. The news of the acts reached Boston in October 1767 when the General Court was out of session. Adams rose to this occasion and organized a boycott. He urged other towns to follow him. By February 1768 several towns in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had taken part in the boycott. Adams along with Otis petitioned the King for removing Governor Bernard from his office. The British Customs Board commissioners could not bring Boston under their clutches which resulted in military assistance. Troops were called to bring Boston in order. Lord Hillsborough ordered for the stationing of four British Army regiments in Boston.

The news of British troops coming to Boston soon arrived leading to the Boston Town Meeting organizing their meet on 12 September 1768. Governor Bernard was requested to convene the General Court to which he refused. Town Meeting called the representatives of other Massachusetts towns for a meeting at Faneuil Hall which started on 22 September 1768. This was the first effective yet unofficial session held by the Massachusetts House which was attended by delegates of more than 100 towns. British troops had already reached Boston harbour when the convention ended. In October 1768 two British regiments were brought down and other two were brought out in November 1768. Military occupation of Boston made Adams leave his reconciliation thoughts and acts. He started to take up works for the development of the American Independence. In 1775 Adams did not join the ongoing American Revolutionary War like many of his peers. According to historians Adams played the role of a reformer at this time rather than a revolutionary. Adams kept relying on changes in the British ministry and policies and warned the British rule that American independence would soon follow the failure of the proposed British ministry changes.

Adams took a leading role in the events that led up to the famous Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, although the precise nature of his involvement has been disputed.

In May 1773, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act, a tax law to help the struggling East India Company, one of Great Britain’s most important commercial institutions. Britons could buy smuggled Dutch tea more cheaply than the East India Company’s tea because of the heavy taxes imposed on tea imported into Great Britain, and so the company amassed a huge surplus of tea that it could not sell.

The Tea Act was forcible selling of tea to the colonies. This act greatly snubbed the local American tea sellers and threatened the colonial economy. The act started off great protests in the colonies. Adams rose to this occasion and joined hands with his associates and committees to oppose the Tea Act. Protestors in all the colonies, except Massachusetts drove away the tea consignees to England or made them resign. Great Britain did not take this lightly and soon bombarded Boston with several Coercive Acts – the Boston Port Act which closed down Boston’s commerce till the East India Company had been repaid for the destroyed tea, The Massachusetts Government Act rewrote the Massachusetts Charter which made many officials get royally appointed rather than elected which resulted in severe restriction of town meetings’ activities, The Administration of Justice Act allowed colonists charged with crimes to be transported to another colony or to Great Britain for trial and a new royal governor was appointed to enforce all these acts who was General Thomas Gage, also made the commander of British military forces in North America.

Adams kept on writing several letters and essays (that accounted daily events in Boston during Britain’s military rule) that came out as published newspaper articles, against British policies. Adams strived hard to make the British withdraw the troops. On 1 August 1769 Boston celebrated Governor Bernard’s leaving of Massachusetts. In 1769 two British regiments were removed from Boston. In March 1770 the infamous Boston Massacre took place where 5 civilians were killed when a clash between soldiers and civilians took place. After the Boston Massacre, Adams along with other town leaders met Governor Bernard’s successor, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, and Colonel William Dalrymple, the army commander, to demand the withdrawal of the troops. Although tension existed, Dalrymple willingly agreed to remove both the regiments to Castle William. Adams supported trial to prove the fact that Boston was on fire due to unjust treatment and not due to unruly mobs making a mess.

Revolution

Adams formed groups to resist the Coercive Acts. In May 1774 during Adam’s role as the moderator the Boston Town Meeting opted for an organized economic boycott of British goods.

Adams remained active in politics upon his return to Massachusetts. He frequently served as moderator of the Boston Town Meeting, and was elected to the state senate, where he often served as that body’s president.

Adams focused his political agenda on promoting virtue, which he considered essential in a republican government. If republican leaders lacked virtue, he believed, liberty was endangered. His major opponent in this campaign was his former protégé John Hancock; the two men had a falling out in the Continental Congress. Adams disapproved of what he viewed as Hancock’s vanity and extravagance, which Adams believed were inappropriate in a republican leader. When Hancock left Congress in 1777, Adams and the other Massachusetts delegates voted against thanking him for his service as president of Congress. The struggle continued in Massachusetts. Adams thought that Hancock was not acting the part of a virtuous republican leader by acting like an aristocrat and courting popularity. Adams favored James Bowdoin for governor, and was distressed when Hancock won annual landslide victories.

The Continental Congress was kept under wraps so Adam’s role has not been recorded. Adams advocated a cautious independence approach urging correspondents back in Massachusetts to wait for more moderate colonists to come in support of the separation from Great Britain. In 1775 Adams was satisfied with the colonies replacing their old governments with independent republican governments. On 7 June 1776 Adams’s political ally Richard Henry Lee presented a three-part resolution calling for Congress to declare independence, create a colonial confederation, and seek foreign aid. After a delay to rally support, Congress approved the United States Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, which Adams signed. Congress continued managing the war effort even after the Declaration of Independence. Adams returned to Boston in 1779 for being present in a state constitutional convention. Adams along with his cousin John Adams and James Bowdoin were appointed as a three-man drafting committee. They came out with the draft of the Massachusetts Constitution which was soon amended by the convention and approved by voters in 1780. The brand new constitution started off a republican government set up.

Retirement

Adams retired from the Continental Congress in 1781. He faced health difficulties which resulted in troubled writing. He returned to Boston in 1781 and never left Massachusetts for his remaining years. Adams’ return to Massachusetts made him become active in politics. He remained as the moderator of the Boston Town Meeting where he was elected to the state senate serving as that body’s president. Adams thought of joining national politics yet again and so he put forward his name as a candidate for the United States House of Representatives in the December 1788 election where he lost to Fisher Ames as Ames was more popular and a stronger supporter of the Constitution. In 1789 Adams got elected as Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. Adams kept continuing his strife for amendments in the constitution which resulted in the passing of the Bill of Rights in 1791. With the addition of the amendments Adams started supporting the Constitution. Adams ended his political career by retiring as governor in 1797.

Death and Legacy

Adams was known to have suffered greatly from an illness known as essential tremor which brought movement disorder. He was unable to write in his later years. On 2 October 1803 Adams died at the age of 81.

Samuel Adams is a controversial figure in American history. Disagreement about his significance and reputation began before his death and continues to the present.

Adams’ contemporaries, both friends and foes, regarded him as one of the foremost leaders of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson, for example, characterized Adams as “truly the Man of the Revolution.” Leaders in other colonies were compared to him; Cornelius Harnett was called the “Samuel Adams of North Carolina”, Charles Thomson the “Samuel Adams of Philadelphia”, and Christopher Gadsden the “Sam Adams of the South”. When John Adams traveled to France during the Revolution, he had to explain that he was not Samuel, “the famous Adams”.

In the late 19th century, many American historians were uncomfortable with contemporary revolutions and found it problematic to write approvingly about Adams. Relations had improved between the United States and the United Kingdom, and Adams’ role in dividing Americans from Britons was increasingly viewed with regret.