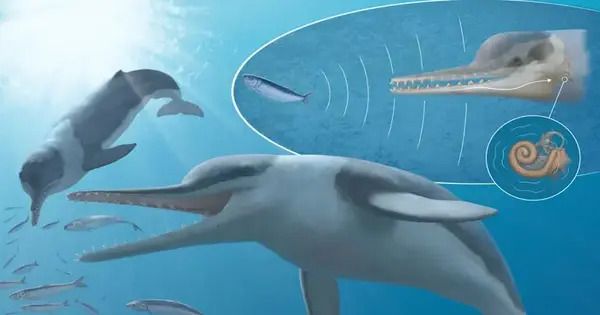

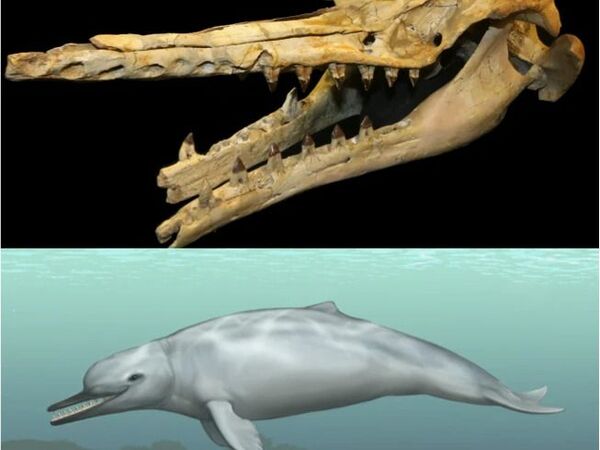

Genetic data suggests that the acoustic fat masses in toothed whales’ heads were formerly jaw muscles and bone marrow. Dolphins and whales utilize sounds to communicate, navigate, and hunt. According to new research, toothed whales’ fatty tissue collections may have developed from their cranial muscles and bone marrow.

Hokkaido University scientists determined the DNA sequences of genes expressed in acoustic fat bodies, which are accumulations of fat around the head used by toothed whales for echolocation. They examined gene expression in the harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) and the Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens). The findings were reported in the journal Gene.

The evolution of acoustic fat bodies in the head – the melon in the whale forehead, extramandibular fat bodies (EMFB) alongside the jawbone, and intramandibular fat bodies (IMFB) within the jawbone – was essential for sound use such as echolocation. However, little is known about the genetic origins of those fatty tissues.

This study has revealed that the evolutionary tradeoff of masticatory muscles for the EMFB — between auditory and feeding ecology – was crucial in the aquatic adaptation of toothed whales. It was part of the evolutionary shift away from chewing to simply swallowing food, which meant the chewing muscles were no longer needed.

Assistant Professor Takashi Hayakawa

“Toothed whales have undergone significant degenerations and adaptations to their aquatic lifestyle,” stated Hayate Takeuchi, a PhD student at Hokkaido University’s Hayakawa Lab and the study’s first author. One adaptation was the partial loss of their senses of smell and taste, as well as the acquisition of echolocation to help them navigate in the underwater environment.

The researchers discovered that genes typically connected with muscle function and development were activated in the melon and EMFBs. There was also evidence of an evolutionary link between extramandibular fat and the masseter muscle, which connects the lower jawbone to the cheeks and is an important muscle in chewing.

“This study has revealed that the evolutionary tradeoff of masticatory muscles for the EMFB — between auditory and feeding ecology — was crucial in the aquatic adaptation of toothed whales,” said Assistant Professor Takashi Hayakawa of the Faculty of Environmental Earth Science, who led the study. “It was part of the evolutionary shift away from chewing to simply swallowing food, which meant the chewing muscles were no longer needed.”

Gene expression analysis in the intramandibular fat revealed the presence of immune function-related genes, such as those that activate certain immune response elements and regulate T cell production.

Another essential part of the research is the Stranding Network Hokkaido (SNH), which collected the samples for this investigation. SNH has collected samples of stranded whales from the coast and river mouths of Hokkaido. “Long-term communication with local people and communities in Hokkaido has enabled researchers to conduct various studies of whale biology, including our surprising findings,” stated SNH’s director, Professor Takashi Fritz Matsuishi.