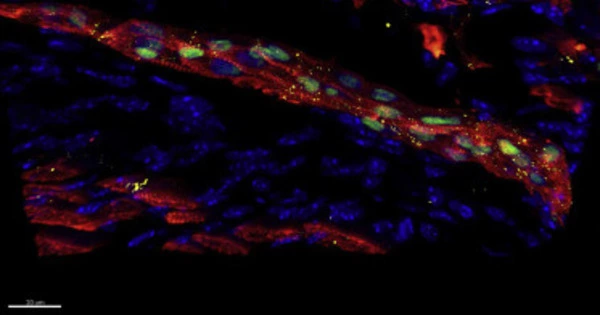

Skin is a vital tissue in our bodies. It protects us from infection and dehydration and allows us to feel a wide range of sensations such as pressure and heat. Throughout our lives, our skin must be constantly renewed. It is maintained in good condition by a variety of stem cells.

Cell differentiation refers to the process by which cells become more specialized. Not all cells in multicellular organisms are alike and have different jobs to help the body maintain a steady state of internal conditions, known as homeostasis. Different types of cells combine to form tissues and organs that function to keep the body alive.

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and at Yale University in U.S. have uncovered how stem cells behave in real-time while adapting their gene expression for differentiation. The study is published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

Skin is essential for protecting our body from outside harm, such as injury, microbes, and radiation. This protective skin function is maintained by the tireless effort of resident stem cells to self-renew (remain stem cells) and differentiate (produce specialized cells) throughout our lifetime.

With sequencing of individual skin cells, we were able to describe genes that get activated or deactivated at different stages during skin maturation, which was essential for uncovering skin renewal as a continuous differentiation process.

Karl Annusver

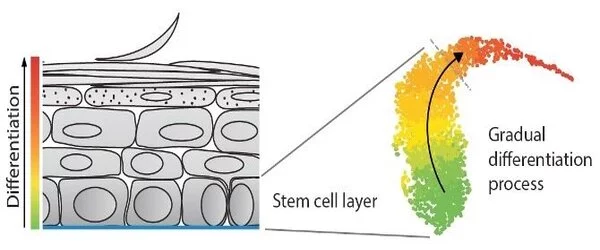

Skin stem cells residing in the epidermis give birth to daughter cells that eventually become specialized barrier cells, forming our protective, watertight skin. This skin renewal process has been previously thought to depend on multiple types of stem cell populations with long- and short-term abilities to produce new daughter cells.

Instead, this new study revealed that these different populations are a snapshots of a gradual differentiation process, where a single stem cell population and their differentiating daughter cells flexibly adjust to local demands. That is, in response to different environments and needs, stem cells rapidly create more, or fewer, specialized daughter cells which surprisingly is not coupled with cell cycle exit as previously thought.

Importantly, changes in such cell behaviors underlie an extensive list of diseases such as cancer (increased stem cell self-renewal) or age-related impaired wound healing (reduced stem cell activity). Thus, it is significant to first understand “how” stem cells and their daughter cells behave, and “how quick” stem cell differentiation can occur.

To answer these questions, researchers from Karolinska Institutet and Yale University teamed up to study stem cell behavior in real time with the corresponding gene expression changes at the same time. “With sequencing of individual skin cells, we were able to describe genes that get activated or deactivated at different stages during skin maturation, which was essential for uncovering skin renewal as a continuous differentiation process,” says Karl Annusver, co-first author of the study in the lab of Maria Kasper, associate professor at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology.

“Through live imaging we observed how skin stem cells create daughter cells on demand, with built-in flexibility to respond to different environments and needs,” said co-first author Katie Cockburn, post-doctoral fellow in the lab of Valentina Greco, Carolyn Walch Slayman Professor of Genetics at Yale University.