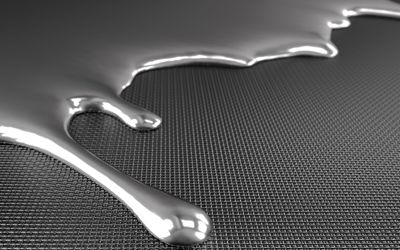

Liquidmetal – also known as amorphous metal or bulk metallic glass is unlike any other material at the most basic level. Liquidmetal and Vitreloy are commercial names of a series of amorphous metal alloys developed by a California Institute of Technology (Caltech) research team and marketed by Liquidmetal Technologies. In an ideal materials world, Liquidmetal would be used as a hard, non-deforming, non-corroding, and generally scratch-resistant case.

Liquidmetal alloys combine a number of desirable material features, including high tensile strength, excellent corrosion resistance, very high coefficient of restitution, and excellent anti-wearing characteristics, while also being able to be heat-formed in processes similar to thermoplastics.

Liquidmetal alloys combine a number of desirable material features, including high tensile strength, excellent corrosion resistance, very high coefficient of restitution, and excellent anti-wearing characteristics, while also being able to be heat-formed in processes similar to thermoplastics. Building on this development, Liquidmetal has become the world’s leader in amorphous metal applications, developing components for medical, automotive, and a wide range of industrial products. Despite the name, they are not liquid at room temperature.

Liquidmetal was introduced for commercial applications in 2003. It is used for, among other things, golf clubs, watches and covers of cell phones. In one experiment, three marble-sized balls made of steel were dropped from the same height into their own glass tubes. Liquidmetal is useful anywhere you could imagine an extremely hard, somewhat flexible, easily mouldable component to be useful. It is conceivable that Apple will soon also be in business with the military, aerospace companies, and deep-sea drilling companies, as they have the ability to now license this material out to these types of industries.

The alloy was the end result of a research program into amorphous metals carried out at Caltech. Achieving a similar combination of properties with crystalline alloys would be nearly impossible, requiring costly post-processing. It was the first of a series of experimental alloys that could achieve an amorphous structure at relatively slow cooling rates.

What makes Liquidmetal special compared to other amorphous alloys is that it is easier to make. Amorphous metals had been made before, but only in small batches because cooling rates needed to be in the millions of degrees per second. To simplify, it doesn’t need to be cooled as quickly as other similar materials, meaning the process is cheaper and easier, and greater quantities can be produced. For example, amorphous wires could be fabricated by splat quenching a stream of molten metal on a spinning disk. Liquidmetal alloys are proprietary amorphous alloys that possess a combination of performance, processing, and potential cost advantages that we believe will make them preferable to other materials in a variety of applications. More recently, a number of additional alloys have been added to the Liquidmetal portfolio.

Information Source: