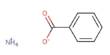

According to research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, scientists have synthesized seven crystal forms of imidacloprid, one of the world’s most extensively used pesticides, in an effort to drastically minimize its environmental effect.

Imidacloprid is an insecticide designed to look like nicotine. Nicotine is a poisonous substance present in many plants, including tobacco. Sucking insects, termites, certain soil insects, and fleas on pets are all controlled with imidacloprid.

The new versions operate up to nine times quicker than the original, allowing for a lower quantity of insecticide to be used to kill disease-carrying mosquitoes while minimizing the risk of harm to other creatures like bees.

“By using modified forms of imidacloprid, we may have a sustainable strategy for improving the insecticide’s ability to control mosquito disease vectors while lessening the quantity needed,” said Bart Kahr, a professor of chemistry at NYU who studies crystal growth, and who led this research.

“This provides a pathway to minimize exposure and harm to other organisms, as well as delay the onset of the development of resistance by mosquitoes, an urgency where malaria is endemic.”

Imidacloprid is a neonicotinoid insecticide that works by attaching to the same receptor as nicotine in the central nervous system of insects. Insects’ neurological systems are disrupted when they land on surfaces coated with imidacloprid because the pesticide molecules are absorbed from crystals through their feet.

A close study of crystal growth may provide a strategy for achieving the goals of preventing infectious diseases with imidacloprid while mitigating the possibility of the development of resistance.

Bart Kahr

Imidacloprid-containing products exist in a variety of forms, including liquids, granules, dust, and water-soluble packaging. Imidacloprid is used in a range of applications, from crop protection to flea treatment for pets; it is also sprayed indoors and outdoors for public health purposes.

Unfortunately, widespread use of imidacloprid in agricultural contexts has been linked to bee colony reduction, which is concerning considering the importance of pollinators for crops and flowers.

Despite the fact that the European Union has outlawed the use of imidacloprid due to its acute toxicity to bees, it is nevertheless available in the United States and used in over 100 other nations. Because it binds better to the receptors of insect nerve cells, imidacloprid is far more poisonous to insects and other invertebrates than it is to mammals and birds.

“Given the widespread use of imidacloprid, we recognized the value in developing more active forms, which could be used in smaller amounts and hopefully spare pollinators,” said Michael Ward, professor of chemistry at NYU and a study author. “We’ve had similar success manipulating another insecticide, deltamethrin, to yield a more rapid crystal version.”

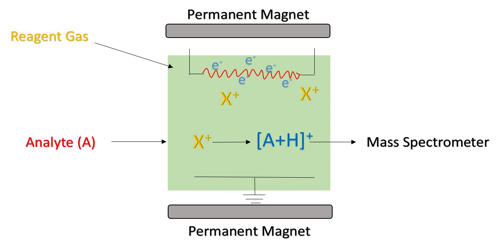

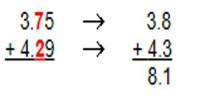

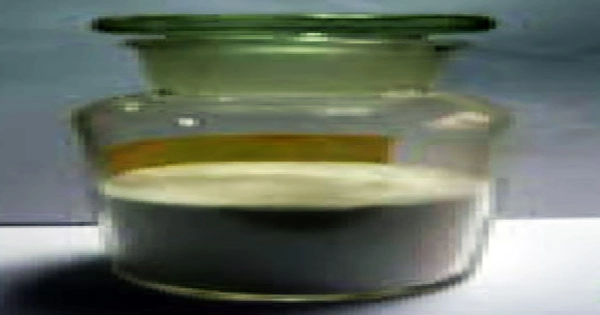

The researchers identified seven novel crystal forms of imidacloprid in a paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, adding to the two current varieties, one of which is used commercially. Xiaolong Zhu, a researcher and study author, developed the majority of the novel crystal forms by melting and cooling commercial forms.

The researchers next tested three stable, novel versions of imidacloprid on disease-carrying mosquitoes and fruit flies (Aedes, which spreads dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika; Anopheles, which transmits malaria; and Culex, which transmits lymphatic filariasis).

The three variants of imidacloprid all killed mosquitos far quicker than the commercial version, with one killing them nine times faster. Insecticides that work fast are critical for killing mosquitoes before they breed or spread illnesses, and they can help to limit the probability of pesticide resistance.

The most active version of imidacloprid, in particular, showed promise for usage outside of the lab and in the field: its crystals were simple to manufacture and stayed stable at ambient temperature.

More active crystal forms are less stable, and they frequently convert into their less stable counterparts, which are less effective insecticides, yet the fastest-acting type of imidacloprid lasted at least six months.

“Imidacloprid is a highly concerning the composition of matter, yet at the same time, it is extremely popular. If regulators in North America will not prohibit it, simple interventions for minimizing environmental exposure may have value,” said Kahr.

“A close study of crystal growth may provide a strategy for achieving the goals of preventing infectious diseases with imidacloprid while mitigating the possibility of the development of resistance.”