Humans have been venturing into the Earth’s mountains, jungles, and deserts for eons. Although the ocean makes up more than 70% of the Earth’s surface, it is still mostly unknown. Since just slightly more than 20% of the ocean floor has been mapped, we really know more about Mars’ surface than we do about the ocean floor.

A more complete image would help us maneuver ships more safely, develop climate models that are more accurate, install communication cables, construct offshore wind farms, and conserve marine species all aspects of the “blue economy,” which is expected to be worth $3 trillion by 2030.

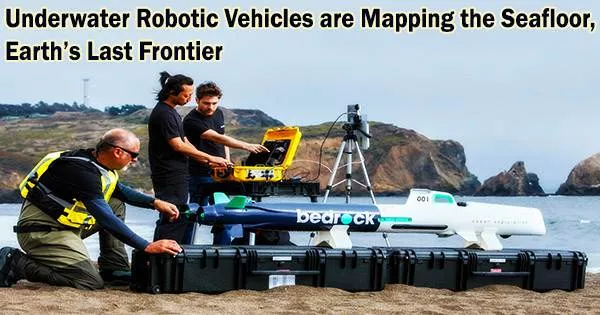

Sensor-equipped underwater robotic vehicles are making it easier and more affordable than ever to collect this data. It is challenging for many of these vehicles to map more remote areas of the sea because they frequently depend on batteries with a finite lifespan and must return to a boat or the shore to recharge.

A five-year-old startup called Seatrec is rising to the challenge, founded by oceanographer Yi Chao. While working at NASA, he developed technology to power ocean robots by harnessing “the naturally occurring temperature difference” of the sea, Chao told CNN Business.

Greener and cheaper

Both Seatrec’s proprietary floating gadget and current data collection robots can be equipped with the power module. This descends a kilometer beneath the surface to study the composition and structure of the seafloor as sonar is used to survey the immediate area. Returning to the surface, the robot uses a satellite to transmit its findings.

Material inside the module either melts or solidifies as the float travels between cooler and warmer ocean regions, creating pressure that in turn generates thermal energy and powers the robot’s generator.

“They get charged by the sea, so they can extend their lifetime almost indefinitely,” Chao said.

A basic float model typically costs around $20,000. Attaching Seatrec’s energy system adds another $25,000, Chao said.

However, Chao claims that over time, data collection can be up to five times more affordable because of the availability of free, renewable energy and the capacity to stay in the water longer. He claimed that although the firm is currently producing less than 100 gadgets annually, mostly for marine researchers, the technology is easily expandable. To increase the range of already-existing mapping devices, Seatrec’s energy module can be retrofitted.

Picking up the pace

New technologies that can extend the reach of data-gathering devices are crucial for mapping more remote parts of the deep sea, according Jamie McMichael-Phillips, director of the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project.

“One of the huge challenges we have is quite simply physics,” said McMichael-Phillips. “Unlike mapping the Earth’s surface where we can use a camera or satellites, at sea, light does not penetrate through the water column. So we’re pretty much limited to using sonar systems.”

Launched in 2017, the Seabed 2030 Project has increased awareness about the importance of the ocean floor, and given researchers and companies a clear goal to work towards: map the entire seafloor by the end of this decade.

Some companies, such as XOCEAN, are surveying the ocean from the surface. Another startup, Bedrock Ocean Exploration, claims that by using an autonomous electric submarine equipped with sonars, cameras, and lasers, it can survey seabed areas up to 10 times faster than conventional methods. The data is then analyzed on Bedrock’s own cloud platform.

The challenge ahead

Even with the growing number of technologies accelerating seabed exploration, completing the map is still a logistical and financial challenge.

Chao estimates that it would take 3,000 of Seatrec’s floats operating over the next 10 years to fully survey the ocean. The company has raised $2 million in seed funding to scale up production of its energy harvesting system.

But this is a drop in the ocean of the capital needed to fully survey the ocean, which is estimated to be “somewhere between $3 to $5 billion,” according to McMichael-Phillips “pretty much the same order of magnitude as the cost of sending a mission to Mars.”

Bedrock’s DiMare believes it’s time we start investing in our own planet.

“If we want to keep Earth as a place that humans can live,” he said, “we have got to get a lot smarter about what’s going on in the ocean.”