A new study discovered that mice treated with peanut-coated microneedles had much higher rates of desensitization to peanut allergy than mice treated with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT). Despite using a dose of peanut protein ten times lower than the dose provided by EPIT, the microneedle treatment proved successful. According to the researchers, the data show that peanut microneedles have the potential to improve food allergy immunotherapy through the skin.

According to a new study, a vaccine can successfully eliminate peanut allergy in mice. According to research from the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan, three monthly doses of a nasal vaccine protected mice from allergic responses when exposed to peanut.

Researchers at the University of Michigan have spent nearly two decades researching a vaccine agent, which has just been converted into the creation of a vaccination to treat food allergies. Immunization of peanut allergy mice, according to the new study, can change how immune cells respond to peanuts in allergic mice. The new method induces a distinct type of immunological response, which prevents allergy reactions.

A recent study reveals that treating peanut allergy using microneedles could greatly enhance desensitization by directly directing the allergen to the skin, giving millions of people with improved protection from severe allergic reactions.

This is a very innovative technology that could provide a unique technique to desensitize people with food allergies. These positive animal results support further development of this platform.

James R. Baker

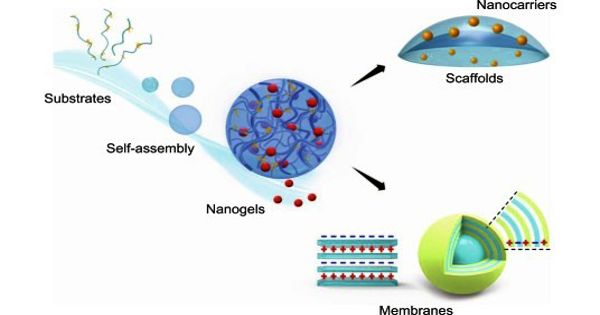

Researchers from Michigan Medicine, in partnership with Moonlight Therapeutics, tested a dermal stamp containing peanut-coated microneedles on mice by putting it to the skin for five minutes once a week for five weeks. They compared it to mice getting epicutaneous immunotherapy, which entails putting a patch on the skin for 24 hours at the same time period.

The findings, published in Immunotherapy, show that mice given five weekly microneedle treatments had significantly higher rates of desensitization to peanut allergy than EPIT, which took two months of treatment to acquire protection. Despite using a dose of peanut protein that was ten times lower than the dose provided by EPIT, the microneedle treatment was successful.

“While our pre-clinical results are from animal models, they demonstrate the potential for peanut microneedles to improve food allergen immunotherapy through the skin,” said Jessica O’Konek, Ph.D., senior author of the paper and research assistant professor at Michigan Medicine’s Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center. “Because treatment options for food allergies are limited, there is a strong incentive for the discovery of innovative therapies. It will be fascinating to see the therapeutic development of this technology” she stated.

Peanut allergies affect around 6 million people in the United States, with symptoms ranging from minor hives to potentially lethal anaphylactic episodes. Currently, the only treatment for peanut allergy recognized by the US Food and Drug Administration is oral immunotherapy. It does, however, necessitate that patients adhere to a stringent long-term procedure for taking each dose.

EPIT has been shown to be safe in clinical trials, however its efficacy has varied. O’Konek believes this is due to the barrier produced by the skin surface, which may reduce the quantity of allergen taken up by the body. Targeted release of peanut protein by microneedle patches may provide a more regulated delivery of allergen.

“This is a very innovative technology that could provide a unique technique to desensitize people with food allergies,” said co-author and head of the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center James R. Baker, Jr., M.D. “These positive animal results support further development of this platform.”

The rodent models investigated reacted to peanut allergies in the same way as humans do, with symptoms such as itchy skin and difficulty breathing. The study looked at protection against allergic responses two weeks after the final dose of vaccination was given.

Researchers are currently conducting studies to assess the duration of protection, but they are optimistic that this strategy will result in long-term allergy suppression. The findings are another step toward a potential clinical study to evaluate the approach in humans in the future.

Further research in mice is planned to better understand the mechanisms underlying food allergy suppression and to determine whether protection from peanut allergies may be extended for an even longer period of time.