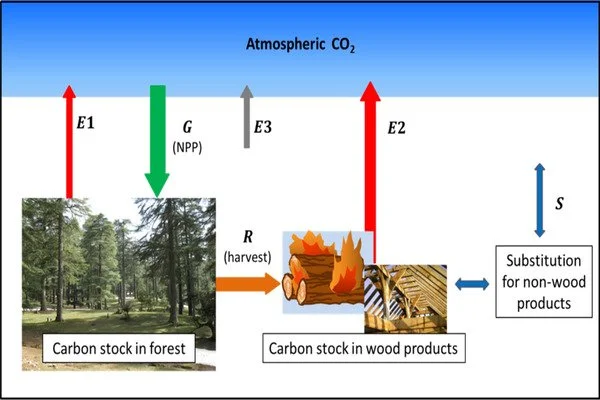

Carbon is cycled through ecosystems in a variety of forms. It is attracted to oxygen and forms gaseous compounds such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO), which can be considered air pollutants and contribute to climate change in high concentrations.

According to a new study, harvested wood products in residential structures will continue to increase carbon storage for the next 50 years. Wood is endlessly useful. Trees store carbon, which is critical for our changing climate. When trees are harvested for wood products such as lumber, some of that carbon is retained. Even after a wood product is discarded, it continues to store carbon.

Wood is used in the construction of more than 90% of new single-family homes in the United States. Every year, approximately 400,000 homes, apartment buildings, and other housing units are destroyed by floods and other natural disasters or decay. Houses are also demolished to make way for new construction.

Because houses store so much carbon, determining how many houses will be built in the future is critical to understanding the total carbon storage capacity of the United States. According to a new USDA Forest Service study published in the journal PLOS ONE, harvested wood products in residential structures will continue to increase carbon storage for the next 50 years.

Forests sequester carbon, and wood produced by forests can hold onto that carbon for decades or centuries. Harvested wood provides an important service to consumers for decades: shelter.

Jeff Prestemon

“Forests sequester carbon, and wood produced by forests can hold onto that carbon for decades or centuries,” says Jeff Prestemon, lead author of the study and research economist with the Southern Research Station. “Harvested wood provides an important service to consumers for decades: shelter.”

Even after residential structures reach the end of their useful life, wood that is stored in landfills, a typical practice in the U.S., does not immediately release its carbon. In this way, wood retains its storage capacity for several more decades.

Prestemon and colleagues, Prakash Nepal of the Forest Products Laboratory and Kamalakanta Sahoo of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, investigated how population growth and income can be combined to project rates of new housing construction at multiple scales (county and region) and for various futures defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). They also wanted to know how future trends in housing starts and housing inventory maintained through repairs and renovations might affect carbon storage in wood products.

“Until now, fine spatial scale projections of carbon in harvested wood products have not been described for the U.S.,” says Prestemon. “Locating future stored carbon will help us better understand emissions risks from structure-destroying disturbances like hurricanes and wildfires.”

Carbon in forests is derived from atmospheric carbon dioxide. Because it circulates through living organisms, this carbon is sometimes referred to as biogenic carbon. Photosynthesis is the process by which trees remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Photosynthesis is used by plants to produce various carbon-based sugars required for tree function and the formation of wood for growth. Carbon is stored in every part of a tree, including the trunk, branches, leaves, and roots.

The study considers five possible futures for the country’s social and economic conditions. The futures, known as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (or SSPs), include population and income growth changes. High (SSP5) and low (SSP3) futures were used to define a plausible range of carbon in harvested wood products over the next few decades.

Researchers described how future construction rates would vary widely across U.S. counties. They translated these construction futures into trends in carbon stored in harvested wood products. These projections show increases in carbon stocks across much of the U.S. Furthermore, carbon additions from construction activities more than offset carbon lost or emitted from structure destruction/demolition. Although housing starts are projected to decline in the future, residential housing and the need to maintain structures will continue to increase carbon storage in wood products for the next several decades.

The study’s projections of single-family and multifamily housing starts at the county level across five potential futures can also help to answer questions about future demand for wood products for construction and where forests and other wildlands are more likely to be replaced by new residential housing development.

“Wood used to build houses will continue to be an increasing, significant component of the overall forest carbon sink for the next 50 years – regardless of whether the US population grows or shrinks, or whether economic growth is high or low,” Prestemon adds.