Full name: Thaddeus Stevens

Date of birth: April 4, 1792

Place of birth: Danville, Vermont, U.S.

Date of death: August 11, 1868 (aged 76)

Place of death: Washington, D.C., U.S.

Occupation: Politician

Political party: Federalist (before 1828); Anti-Masonic (1828–1838); Whig (1838–1853); Know Nothing (1853–1855); Republican (1855–1868)

Father: Joshua Stevens

Mother: Sarah (née Morrill)

Domestic partner: Lydia Hamilton Smith (1848–1868)

Early Life

Thaddeus Stevens (born April 4, 1792, Danville, Vermont, U.S. died on 11th August 1868, Washington, D.C.), a U.S. Radical Republican congressional leader during Reconstruction (1865–77) who fought for freedmen’s rights and insisted on strict conditions for Southern states’ readmission into the Union after the Civil War (1861–65).

Stevens, a vehement opponent of slavery and discrimination against African Americans, led the charge against President Andrew Johnson during Reconstruction to ensure their rights. During the American Civil War, he served as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, focusing his efforts on defeating the Confederacy, financing the war with increased taxes and borrowing, smashing the power of slave owners, abolishing slavery, and ensuring equal rights for freedmen.

Thaddeus was born into poverty in rural Vermont and had a tough childhood because his father abandoned the family when he was a toddler. He was also born with a club foot and developed a limp, limiting his physical movements. Despite his difficulties, he developed into a bright student and went on to become a lawyer.

His anti-slavery activities as a lawyer and politician cost him votes, and he did not seek reelection in 1852. Stevens rejoined the newly created Republican Party after a brief flirtation with the Know-Nothing Party and was re-elected to Congress in 1858. As someone who had been through a lot as a child, he acquired empathy for slaves and other impoverished groups in American society and worked for their equality throughout his legal career.

Stevens contended that slavery should not survive the war, and he was disappointed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s sluggish response to his argument. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, he shepherded the government’s financial legislation through the chamber. When he entered politics, he maintained his social views and became a strong supporter of free education and the abolition of slavery.

Following the Civil War, he became a radical Republican, openly campaigning for black equality. He helped create the Fourteenth Amendment, which subsequently became the foundation for civil rights legislation. Stevens’ final major effort was to secure articles of impeachment against Johnson in the House of Representatives, serving as House manager during the impeachment proceedings, albeit the Senate did not convict the President.

Childhood and Educational Life

Thaddeus Stevens was born in Danville, Vermont on 4th April 1792 as the second of four children of Joshua Stevens, a farmer and cobbler, and his wife Sarah. Thaddeus was born with a club foot. He was named to honor the Polish general who served in the American Revolution, Thaddeus Kościuszko.

His parents were Baptists who had emigrated from Massachusetts around 1786. His father abandoned the family when the children were quite young, leaving behind his wife to raise the children alone. Despite the family’s poverty, Sarah was adamant about educating the children so that they might establish better lives for themselves.

Even with the help of her sons, Sarah Stevens struggled to make a life on the farm. She was determined that her sons improve themselves, and in 1807 moved the family to the neighboring town of Peacham, Vermont, where she enrolled young Thaddeus in the Caledonia Grammar School (often called the Peacham Academy).

Following his graduation, Thaddeus enrolled at the University of Vermont’s Burlington College. He then attended to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he received his bachelor’s degree in 1814. Stevens began studying law under Judge John Mattocks and was later admitted to the Maryland bar.

Personal Life

Stevens never married, though there were rumors about his twenty-year (1848–1868) relationship with his widowed African-American housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith (1813–1884). After the loss of their parents, Stevens adopted two of his nephews, Thaddeus (sometimes known as “Thaddeus Jr.”) and Alanson Joshua Stevens. Lydia was a fair-skinned African-American, but her husband Jacob and at least one of her boys were significantly darker. It’s unclear whether Stevens and Smith had a romantic relationship.

In failing health, Stevens requested that he be buried among Negroes resting in a cemetery in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Working and Political Career

Thaddeus Stevens, an anti-Masonic state legislator from 1833 to 1841, was a supporter of banks, internal improvements, and public schools while opposing Freemasons, Jacksonian Democrats, and slaveholders. The abolitionist movement was in its early stages in the 1830s, with only a few individuals, such as William Lloyd Garrison, taking up the cause.

Stevens’ political career was harmed by his support for the anti-slavery campaign, but it did not stop him from fighting for the cause. Stevens, along with Governor Wolf, shepherded legislation through the legislature in April 1834 that allowed districts across the state to vote on whether or not to create public schools and the taxes that would fund them. The district of Gettysburg voted in favor, and Stevens was chosen as a school director, a position he held until 1839.

He campaigned against African-American disenfranchisement at the Pennsylvania constitutional convention in 1837, refusing to sign the 1837 constitution because of its discriminatory voting provision. He was a Whig in the United States House of Representatives from 1849 to 1853, advocating tariff increases and opposing the 1850 Compromise’s fugitive slave provision.

Stevens rose to prominence as a leading figure in Northern abolitionism in the 1850s. His participation in the anti-slavery campaign, however, had a bad impact on his political career, and he quit the Whig party in 1851. He returned to his law firm, which was booming at the time, while maintaining his political activity. He became a member of the Republican Party, which was anti-slavery, and was elected to Congress in 1859.

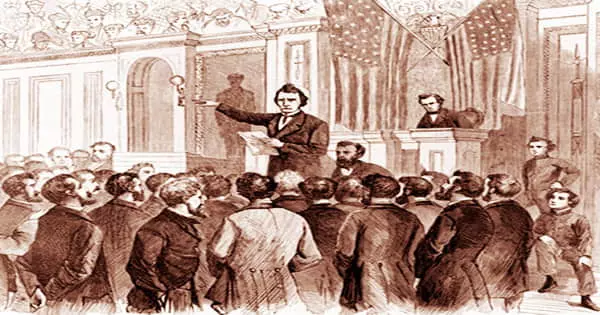

Stevens became, in the words of a fellow member, the “natural leader, who assumed his place by common consent.” He exerted this leadership by means of his sarcastic eloquence, his parliamentary skills, and his privileges as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and later of the Appropriations Committee.

He worked closely with Lincoln administration officials on legislation to finance the war after the Civil War broke out. In order to aid collect funding for the war, he was instrumental in the enactment of the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the National Banking Act of 1863. When Congress gathered in December 1865, Stevens was the driving force behind the exclusion of conventional Southern senators and congressmen.

Stevens relocated his home and practice to Lancaster in 1842. He was well aware that Lancaster County was a stronghold for Anti-Mason and Whig forces, ensuring that he maintained a political base. He earned more than any other Lancaster attorney in a short period of time, and by 1848, he had reduced his debts to $30,000 and paid them off quickly. He was a key figure in the development of the Fourteenth (due process) Amendment to the Constitution and the military reconstruction legislation of 1867 as a member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction.

The Fourteenth Amendment was proposed to address citizenship rights and equal protection under the laws for these former slaves. It was ultimately adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Viewing Pres. Andrew Johnson as “soft” toward the South, he introduced the resolution for his impeachment (1868) and served as chairman of the committee appointed to draft impeachment articles.

During this time, Stevens advocated for the confiscation of Southern plantations and the division of a portion of the land among freedmen, with the earnings going toward paying off the national debt; however, this confiscation scheme failed to obtain congressional approval. Stevens helped establish the National Banking Act in 1863, which obliged banks to limit their currency issues to the number of government bonds they were obligated to hold. The system lasted for half a century before being replaced in 1913 by the Federal Reserve System.

Thaddeus Stevens was a radical politician who battled hard to abolish slavery and promoted equal rights for African-Americans. He urged Congress to draft a constitutional amendment outlawing slavery, which resulted in the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Continuing his efforts, he was instrumental in the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which addressed the issues of former slaves’ equal rights and citizenship.

Retirement and Later Life

Stevens stayed in Washington after Congress adjourned in late July, unable to return to Pennsylvania due to illness. Stevens was suffering from stomach problems, swollen feet, and dropsy. He was unable to leave the house by early August. He did, however, get some visitors and correctly predicted Grant’s victory to his friend and former student Simon Stevens (no relation).

Death and Legacy

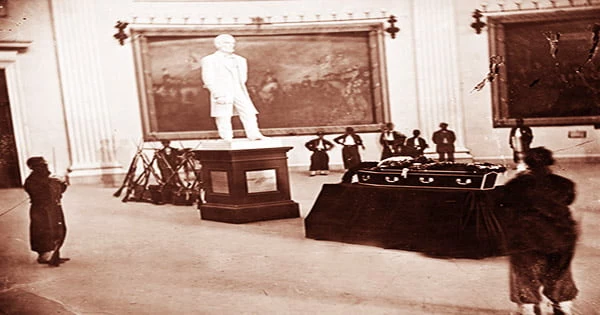

Thaddeus Stevens died on August 11, 1868. Shortly before his death he had requested to be buried in Shreiner-Concord Cemetery in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, because the state accepted all races. Stevens’s body was conveyed from his house to the Capitol by white and black pallbearers together.

Thousands of mourners, of both races, filed past his casket as he lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda; Stevens was the third man, after Clay and Lincoln, to receive that honor. African-American soldiers constituted the guard of honor. On his tombstone were carved the words he had composed, explaining that he had chosen this place so that he might “illustrate in death” the principle he had “advocated throughout a long life”; namely, “Equality of man before his Creator.”

Awards and Honours

A statue of Stevens was unveiled in front of the Adams County Courthouse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on April 2, 2022, as part of a celebration of Stevens’ 230th birthday. The Thaddeus Stevens Society commissioned the statue, which was created by multidisciplinary artist Alex Paul Loza.