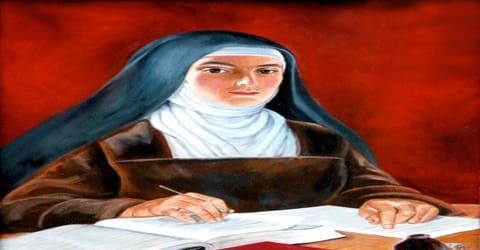

Biography of St Teresa of Ávila

St Teresa of Ávila – A prominent Spanish mystic, Roman Catholic saint, Carmelite nun, author, and theologian.

Name: Saint Teresa of Ávila

Also Known As: Teresa Of Ávila, Saint Teresa Of Jesus, Teresa Sánchez De Cepeda Y Ahumada

Date of Birth: 28 March 1515

Place of Birth: Ávila, Crown of Castile (today Spain)

Date of Death: 4 October 1582 (aged 67)

Place of Death: Alba de Tormes, Salamanca, Spain

Father: Alonso Sánchez de Cepeda

Mother: Beatriz de Ahumada y Cuevas

Early Life

Saint Teresa of Ávila, a Spanish nun, one of the great mystics and religious women of the Roman Catholic Church, and author of spiritual classics, was born in Avila, Spain, March 28, 1515. She was a reformer of the Carmelite Order and a major figure of the Counter-Reformation, a period of Catholic revival initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation during the mid-16th century. She was also a mystic and an author and is considered to be the patron saint of Headache sufferers and Spanish Catholic Writers.

In 1622, forty years after her death, she was canonized by Pope Gregory XV, and, on 27 September 1970, she was named a Doctor of the Church by Pope Paul VI.[5] Her books, which include her autobiography (The Life of Teresa of Jesus) and her seminal work The Interior Castle, are an integral part of Spanish Renaissance literature as well as Christian mysticism and Christian meditation practices. She also wrote Way of Perfection.

Born into a religious household, Saint Teresa was raised by strict and devout Christian parents. From a young age, she was fascinated by the lives of saints and ran away from home at the age of seven to seek martyrdom among the Moors. She was eventually brought back home but nonetheless continued on her quest for spiritual knowledge. The untimely death of her mother when Teresa was just a teenager intensified her devotion towards God and religion as she instinctively turned to the Virgin Mary for comfort.

Saint Teresa later entered a Carmelite Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila and became a nun. She laid the foundation for the Catholic mendicant order, the Discalced Carmelites, or Barefoot Carmelites, along with another Spanish saint, Saint John of the Cross. She was canonized years after her death and more recently, named a Doctor of the Church.

After her death, Saint Teresa was considered a candidate to become a national patron saint in Spain. A Santero image of the Immaculate Conception of El Viejo, said to have been sent with one of her brothers to Peru, was canonically crowned by Pope John Paul II on 28 December 1989 at the Shrine of El Viejo. Pious Catholic beliefs also associate Saint Teresa with the Infant Jesus of Prague with claims of former ownership and devotion.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Saint Teresa of Ávila, also called Saint Teresa of Jesus, original name Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada, was born March 28, 1515, in Gotarrendura, Ávila, Crown of Castile (present-day Spain). Her father, Alonso Sánchez de Cepeda, was a very strict man while her mother, Beatriz de Ahumada y Cuevas, was a religious and kind woman. Her father was a successful wool merchant and one of the wealthiest men in Ávila. Her father bought a knighthood and successfully assimilated into Christian society.

Her father, Alonso de Cepeda, was a son of a Toledan merchant. Early in life when Teresa was 15, her mother died, leaving behind 10 children. Teresa was the “most beloved of them all.” She was of medium height, large rather than small, and generally well proportioned. In her youth, she had the reputation of being quite beautiful, and she retained her fine appearance until her last years. Teresa’s personality was extroverted, her manner affectionately buoyant, and she had the ability to adapt herself easily to all kinds of persons and circumstances.

Her father sent her to the Augustinian nuns at Ávila for her education when she was 16. This rekindled her love for religion and she decided to become a nun of the Carmelite Order and lead a spiritual life.

Personal Life

Saint Teresa of Avila remained active throughout her life. Even when she was well into her sixties she continued founding convents to promote Roman Catholicism. In fact, the convents in northern Andalusia, Palencia, Soria, and Burgos were founded by her towards the end of her life.

Career and Works

Saint Teresa’s mother died in 1529, and, despite her father’s opposition, Teresa entered, probably in 1535, the Carmelite Convent of the Incarnation at Ávila. The following year, Teresa received the habit and began wholeheartedly to give herself to prayer and penance. Shortly after, Teresa became seriously ill and failed to respond to medical treatment and fell into a coma so profound that she was thought to be dead. After 4 days she revived. After her cure, which she attributed to St. Joseph, Teresa entered a period of mediocrity in her spiritual life, but she did not at any time give up praying. During this stage, which lasted 18 years, she experienced a series of transitory mystical experiences.

In 1558 Teresa began to consider the restoration of Carmelite life to its original observance of austerity, which had relaxed in the 14th and 15th centuries. Her reform required utter withdrawal so that the nuns could meditate on divine law and, through a prayerful life of penance, exercise what she termed “our vocation of reparation” for the sins of humankind.

In early 1560 she became acquainted with the Franciscan priest Saint Peter of Alcantara, who became her spiritual guide and counselor. Encouraged by him, she now resolved to found a reformed Carmelite convent. She was helped in her objective by Guimara de Ulloa, a wealthy friend who supplied the funds. Teresa also spent years convincing Spanish Jewish converts to follow Christianity.

In 1562, with Pope Pius IV’s authorization, she opened the first convent (St. Joseph’s) of the Carmelite Reform. A storm of hostility came from municipal and religious personages, especially because the convent existed without endowment, but she staunchly insisted on poverty and subsistence only through public alms.

In March 1563, when Teresa moved to the new cloister, she received the papal sanction to her prime principle of absolute poverty and renunciation of property, which she proceeded to formulate into a “Constitution”. Her plan was the revival of the earlier, stricter rules, supplemented by new regulations such as the three disciplines of ceremonial flagellation prescribed for the divine service every week, and the discalceation of the nun. For the first five years, Teresa remained in pious seclusion, engaged in writing.

In 1567, she received a patent from the Carmelite general, Rubeo de Ravenna, to establish new houses of her order, and in this effort and later visitations, she made long journeys through nearly all the provinces of Spain. Of these, she gives a description in her Libro de las Fundaciones.

She established several reform convents at Medina del Campo, Malagón, Valladolid, Toledo, Pastrana, Salamanca, and Alba de Tormes between 1567 and 1571. She was also given the permission to set up two houses for men who wished to adopt the reforms.

As part of her original patent, Teresa was given permission to set up two houses for men who wished to adopt the reforms; she convinced John of the Cross and Anthony of Jesus to help with this. They founded the first convent of Discalced Carmelite Brethren in November 1568 at Duruello. Another friend, Jerónimo Gracián, Carmelite visitator of the older observance of Andalusia and apostolic commissioner, and later provincial of the Teresian reforms, gave her powerful support in founding convents at Segovia (1571), Beas de Segura (1574), Seville (1575), and Caravaca de la Cruz (Murcia, 1576), while the deeply mystical John, by his power as teacher and preacher, promoted the inner life of the movement.

The gift of God to Teresa in and through which she became holy and left her mark on the Church and the world is threefold: She was a woman; she was a contemplative; she was an active reformer. St. Teresa’s great work of reform began with herself. She made a vow always to follow the more perfect course, and resolved to keep the rule as perfectly as she could. Teresa received permission from Rome to establish a reformed convent (she went on to found over a half-dozen new monasteries,) even though her efforts at reform were oftentimes misunderstood, misjudged and opposed. Yet she struggled on, courageous and faithful; she struggled with her own mediocrity, her illness, her opposition. And in the midst of all this, she clung to God in life and in prayer.

In 1575, while she was at the Sevilla (Seville) convent, a jurisdictional dispute erupted between the friars of the restored Primitive Rule, known as the Discalced (or “Unshod”) Carmelites, and the observants of the Mitigated Rule, the Calced (or “Shod”) Carmelites. Although she had foreseen the trouble and endeavored to prevent it, her attempts failed. The Carmelite general, to whom she had been misrepresented, ordered her to retire to a convent in Castile and to cease founding additional convents; Juan was subsequently imprisoned at Toledo in 1577.

In 1576, a series of persecutions began on the part of the older observant Carmelite order against Teresa, her friends, and her reforms. Pursuant to a body of resolutions adopted at the general chapter at Piacenza, the “definitors” of the order forbade all further founding of convents. The general chapter condemned her to voluntary retirement to one of her institutions. She obeyed and chose St. Joseph’s at Toledo. Her friends and subordinates were subjected to greater trials.

In 1579, largely through the efforts of King Philip II of Spain, who knew and admired Teresa, a solution was effected whereby the Carmelites of the Primitive Rule were given independent jurisdiction, confirmed in 1580 by a rescript of Pope Gregory XIII. Teresa, broken in health, was then directed to resume the reform. In journeys that covered hundreds of miles, she made exhausting missions and was fatally stricken en route to Ávila from Burgos.

In 1580 she wrote the ‘Castillo interior/ Las moradas’ (Interior castle/ The mansions) which went on to become her best known literary work. She described the various stages of spiritual evolution leading to full prayer.

During the last three years of her life, Teresa founded convents at Villanueva de la Jara in northern Andalusia (1580), Palencia (1580), Soria (1581), Burgos, and Granada (1582). In total, seventeen convents, all but one founded by her, and as many men’s cloisters were due to her reform activity of twenty years.

Toward the end of her life, she exclaimed: “Oh, my Lord! How true it is that whoever works for you is paid in troubles! And what a precious price to those who love you if we understand its value.” Teresa’s writings, especially the Way of Perfection and The Interior Castle, have helped generations of believers. Her writings on prayer and contemplation are drawn from her experience: powerful, practical and graceful.

Awards and Honor

Saint Teresa of Avila was canonized by Pope Gregory XV in 1622, forty years after her death.

In December 1970, Pope Paul VI conferred upon her the papal honor of Doctor of the Church, making her one of the first women to be awarded the distinction.

Saint Teresa is revered as the Doctor of Prayer. The mysticism in her works exerted a formative influence upon many theologians of the following centuries, such as Francis of Sales, Fénelon, and the Port-Royalists.

Death and Legacy

(Statue of Saint Teresa of Ávila in Mafra National Palace, Mafra)

Her final illness overtook her on one of her journeys from Burgos to Alba de Tormes. She died in 1582, just as Catholic nations were making the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, which required the removal of 5–14 October from the calendar. She died either before midnight of 4 October or early in the morning of 15 October which is celebrated as her feast day. (According to liturgy as then in use, she died on the 15th in any case, counted from the sunset of the preceding day; 4 October, as it were, is occupied precisely on that rationale by the feast of St. Francis, who died on the evening of the 3rd.)

Her last words were: “My Lord, it is time to move on. Well then, may your will be done. O my Lord and my Spouse, the hour that I have longed for has come. It is time to meet one another.”

Teresa’s ascetic doctrine has been accepted as the classical exposition of the contemplative life, and her spiritual writings are among the most widely read. Her Life of the Mother Teresa of Jesus (1611) is autobiographical; the Book of the Foundations (1610) describes the establishment of her convents. Her writings on the progress of the Christian soul toward God are recognized masterpieces: The Interior Castle (1588), Spiritual Relations, Exclamations of the Soul to God (1588), and Conceptions on the Love of God. Of her poems, 31 are extant; of her letters, 458.

Another one of her famous works is ‘The Way of Perfection’ (1583) in which she describes a method for making progress in the contemplative life. She called this a “living book” as she had detailed the way of progressing through prayer and Christian medication, and also explained the purpose and approaches to spiritual life.

Information Source: