Biography of Sadi Carnot

Sadi Carnot – French military scientist and physicist.

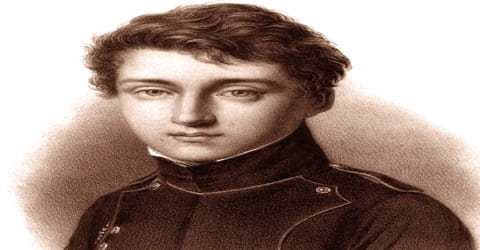

Name: Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot

Date of Birth: 1 June 1796

Place of Birth: Palais du Petit-Luxembourg, Paris, France

Date of Death: 24 August 1832 (aged 36)

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Physicist

Father: Lazare Carnot

Early Life

A French scientist who described the Carnot cycle, relating to the theory of heat engines, Sadi Carnot was born on 1 June 1796 in Paris, France into a family that was distinguished in both science and politics.

Popularly described as the “Father of Thermodynamics”, Sadi Carnot was the man behind the first successful theoretical account of heat engine, today is known as the Carnot cycle. A man with a mission, Carnot did not let the unrest and instability of his early life overshadow his living. He is accounted for concepts such as Carnot efficiency, Carnot theorem and the Carnot heat engine amongst others. His book, Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, laid the foundations for the second law of thermodynamics. Carnot’s concept of the idealized heat engine led to the development of a thermodynamic system that could be quantified, a key success that enabled many of the future discoveries that lay ahead. Read further to know more on the life of this prolific scientist and engineer.

Like Copernicus, Sadi Carnot published only one book, the Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire (Paris, 1824), in which he expressed, at the age of 27 years, the first successful theory of the maximum efficiency of heat engines. In this work, he laid the foundations of an entirely new discipline, thermodynamics. Carnot’s work attracted little attention during his lifetime, but it was later used by Rudolf Clausius and Lord Kelvin to formalize the second law of thermodynamics and define the concept of entropy.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Sadi Carnot, in full Nicolas-léonard-sadi Carnot (French: kaʁno), was born on June 1, 1796, in Paris, France. He was the first son of Lazare Carnot, an eminent mathematician, military engineer and leader of the French Revolutionary Army. Lazare chose his son’s third given name (by which he would always be known) after the Persian poet Sadi of Shiraz. Sadi was the elder brother of statesman Hippolyte Carnot and the uncle of Marie François Sadi Carnot, who would serve as President of France from 1887 to 1894.

In 1812, the 16-year-old Sadi Carnot was admitted to the highly esteemed École Polytechnique in Paris. His instructors included Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, Siméon Denis Poisson, and André-Marie Ampère; fellow students included famous future scientists Claude-Louis Navier, and Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis. During his time in school, Carnot developed a special interest in the theory of gases and solving industrial engineering problems.

After graduating in 1814, Sadi became an officer in the French army’s corps of engineers. His father Lazare had served as Napoleon’s minister of the interior during the “Hundred Days”, and after Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815 Lazare was forced into exile. Sadi’s position in the army, under the restored Bourbon monarchy of Louis XVIII, became increasingly difficult. Sadi Carnot was posted to different locations; he inspected fortifications, tracked plans and wrote many reports. It appears his recommendations were ignored and his career was stagnating. On 15 September 1818, he took a six-month leave to prepare for the entrance examination of Royal Corps of Staff and School of Application for the Service of the General Staff.

During this time, Sadi Carnot, too, wasn’t very happy with his life on the professional front. Though he had the job of inspecting fortifications, drawing up plans and writing reports, his recommendations were mistreated and ignored. Due to his lack of promotion and inability to find himself a job that helped him make use of his training, in 1819, Carnot gave an examination to join the then formed General Staff Corps in Paris. Fortunately, he passed the paper and took up the job. During this time, Sadi Carnot began to attend courses at various institutions in Paris, including the Sorbonne and the Collège de France. It was then that his interest in industrial problems grew and he began to study the theory of gases.

Personal Life

On Sadi Carnot’s religious views, he was a Philosophical theist. As a deist, he believed in divine causality, stating that “what to an ignorant man is chance, cannot be chance to one better instructed,” but he did not believe in divine punishment. He criticized established religion, though at the same time spoke in favor of “the belief in an all-powerful Being, who loves us and watches over us.” He was a reader of Blaise Pascal, Molière and Jean de La Fontaine.

Career and Works

In 1819, Sadi Carnot transferred to the newly formed General Staff, in Paris. He remained on call for military duty, but from then on he dedicated most of his attention to private intellectual pursuits and received only two-thirds pay. Carnot befriended the scientist Nicolas Clément and attended lectures on physics and chemistry.

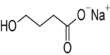

In 1823, after the death of Lazare Carnot, Hippolyte Carnot returned to Paris and helped Sadi Carnot, who was then working on the book on steam engines aiming to answer two questions. Firstly, whether there was an upper limit to the power of heat, and secondly whether there were a better means than steam to produce this power.

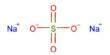

In 1824, Sadi Carnot published Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu et sur les machines propres à développer Cette puissance (Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire), which detailed his research and presented a well-reasoned theoretical treatment for the perfect (but unattainable) heat engine, now known as the Carnot cycle. In the first stage of his model, the piston moves downward while the engine absorbs heat from a source and gas begins to expand. In the second stage, as the piston continues to move downward, the heat is removed; the gas still expands but this time through a temperature drop. In the third stage, the piston starts to rise and the gas is compressed again, driving off heat (isothermal compression). In the fourth stage, the piston continues to move upward, the cooled gas is compressed, and the temperature rises.

Sadi Carnot saw that, in a steam engine, motive power is produced when heat “drops” from the higher temperature of the boiler to the lower temperature of the condenser, just as water, when falling, provides power in a waterwheel. He worked within the framework of the caloric theory of heat, assuming that heat was a gas that could be neither created nor destroyed. Though the assumption was incorrect and Carnot himself had doubts about it even while he was writing, many of his results were nevertheless true, notably the prediction that the efficiency of an idealized engine depends only on the temperature of its hottest and coldest parts and not on the substance (steam or any other fluid) that drives the mechanism.

Sadi Carnot realized that the conduction of heat between parts of the engine at different temperatures had to be eliminated to maximize efficiency. He also introduced the concept of reversibility, whereby motive power can be used to produce the temperature difference in the engine. Also some of the theories he determined laid the groundwork for the discovery of the second law of thermodynamics. Perhaps the most important contribution Carnot made to thermodynamics was his abstraction of the essential features of the steam engine, as they were known in his day, into a more general and idealized heat engine. This resulted in a model thermodynamic system upon which exact calculations could be made, and avoided the complications introduced by many of the crude features of the contemporary steam engine.

Sadi Carnot showed that the efficiency of this idealized engine is a function only of the two temperatures of the reservoirs between which it operates. He did not, however, give the exact form of the function, which was later shown to be (T1−T2)/T1, where T1 is the absolute temperature of the hotter reservoir. (Note: This equation probably came from Kelvin.) No thermal engine operating any other cycle can be more efficient, given the same operating temperatures. The Carnot cycle is the most efficient possible engine, not only because of the (trivial) absence of friction and other incidental wasteful processes; the main reason is that it assumes no conduction of heat between parts of the engine at different temperatures. Carnot knew that the conduction of heat between bodies at different temperatures is a wasteful and irreversible process, which must be eliminated if the heat engine is to achieve maximum efficiency.

Although formally presented to the Academy of Sciences and given an excellent review in the press, the work was completely ignored until 1834, when Émile Clapeyron, a railroad engineer, quoted and extended Carnot’s results. Several factors might account for this delay in recognition; the number of copies printed was limited and the dissemination of scientific literature was slow, and such work was hardly expected to come from France when the leadership in steam technology had been centered in England for a century.

Sadi Carnot also introduced the concept of reversibility in his book, according to which motive power could be used to produce the temperature difference in the engine, a concept subsequently known as thermodynamic reversibility. Though formulated in terms of caloric, rather than entropy, this was an early rendition of the second law of thermodynamics. Though Sadi Carnot’s book garnered excellent reviews as soon as it was published, it acclaimed public attention only after Clapeyron published an analytic reformulation of it in 1834.

Little is known of Carnot’s subsequent activities. In 1828 he described himself as a “constructor of steam engines, in Paris.” When the Revolution of 1830 in France seemed to promise a more liberal regime, there was a suggestion that Carnot be given a government position, but nothing came of it. He was also interested in improving public education. When the absolutist monarchy was restored, he returned to scientific work, which he continued until his death in the cholera epidemic of 1832 in Paris.

Eventually, Sadi Carnot’s views were incorporated by the thermodynamic theory as it was developed by Rudolf Clausius in Germany (1850) and William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) in Britain (1851).

Death and Legacy

Nicolas-léonard-sadi Carnot died during a cholera epidemic on 24 August 1832, at the age of 36, in Paris, France. Because of the contagious nature of cholera, many of Carnot’s belongings and writings were buried together with him after his death. As a consequence, only a handful of his scientific writings survived.

With his multiple scientific contributions, including the Carnot heat engine, Carnot theorem, and Carnot efficiency, Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot is often described as the “Father of Thermodynamics.” His concept of the idealized heat engine led to the development of a thermodynamic system that could be quantified, a key success that enabled many of the future discoveries that lay ahead.

Information Source: