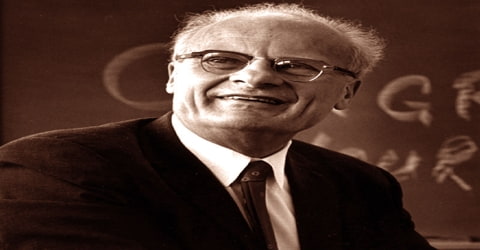

Biography of Paavo Nurmi

Paavo Nurmi – Finnish middle-distance and long-distance runner.

Name: Paavo Johannes Nurmi

Date of Birth: 13 June 1897

Place of Birth: Turku, Finland

Date of Death: 2 October 1973 (aged 76)

Place of Death: Helsinki, Finland

Occupation: Athlete

Father: Johan Fredrik Nurmi

Mother: Matilda Wilhelmiina Laine

Spouse/Ex: Sylvi Laaksonen (m. 1932- d. 1935)

Children: Matti

Early Life

Paavo Nurmi, a Finnish track athlete who dominated long-distance running in the 1920s, capturing nine gold medals in three Olympic Games (1920, 1924, 1928), as well as three silvers, was born on 13 June 1897, in Turku, Finland, to carpenter Johan Fredrik Nurmi and his wife Matilda Wilhelmiina Laine. He was nicknamed the “Flying Finn” as he dominated distance running in the early 20th century. Nurmi set 22 official world records at distances between 1500 meters and 20 kilometers and won nine gold and three silver medals in his twelve events in the Olympic Games. At his peak, Nurmi was undefeated for 121 races at distances from 800 m upwards. Throughout his 14-year career, he remained unbeaten in cross country events and the 10,000 m.

Nurmi could run 1500 meters in 5:02, by the age of 11. Finland runner Hannes Kolehmainen’s performance in the 1912 Summer Olympics inspired Nurmi to focus on his love of running. He set his first national record for the 3000 m on May 29, 1920, and in June won both the 1500 m and 5000 m at the Olympic trials. In 1923, Nurmi became the first runner to hold simultaneous world records in the mile, the 5000 m and the 10,000 m races, a feat which has never since been repeated. He set new world records for the 1500 m and the 5000 m with just an hour between the races and took gold medals in both distances in less than two hours at the 1924 Olympics. Seemingly unaffected by the Paris heat wave, Nurmi won all his races and returned home with five gold medals, although he was frustrated that Finnish officials had refused to enter him for the 10,000 m.

Struggling with injuries and motivation issues after his exhaustive U.S. tour in 1925, Nurmi found his long-time rivals Ville Ritola and Edvin Wide ever more serious challengers. At the 1928 Summer Olympics, Nurmi recaptured the 10,000 m title but was beaten for the gold in the 5000 m and the 3000 m steeplechase. He then turned his attention to longer distances, breaking the world records for events such as the one hour run and the 25-mile marathon. Nurmi intended to end his career with a marathon gold medal, as his idol Kolehmainen had done. In a controversial case that strained Finland–Sweden relations and sparked an inter-IAAF battle, Nurmi was suspended before the 1932 Games by an IAAF council that questioned his amateur status; two days before the opening ceremonies, the council rejected his entries. Although he was never declared a professional, Nurmi’s suspension became definite in 1934 and he retired from running.

For eight years (1923–31) he held the world record for the mile run: 4 min 10.4 sec. During his career, he established 25 world records at various distances. Nurmi later coached Finnish runners, raised funds for Finland during the Winter War, and worked as a haberdasher, building contractor, and share trader, eventually becoming one of Finland’s richest people.

In 1952, Nurmi was the lighter of the Olympic Flame at the Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Nurmi’s running speed and elusive personality spawned nicknames such as the “Phantom Finn”, while his achievements, training methods, and running style influenced future generations of middle- and long-distance runners. Nurmi, who rarely ran without a stopwatch in his hand, has been credited for introducing the “even pace” strategy and analytic approach to running, and for making running a major international sport.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Paavo Nurmi, in full Paavo Johannes Nurmi (Finnish pronunciation: ˈpɑːʋo ˈnurmi), was born on June 13, 1897, at Turku, Finland, to carpenter Johan Fredrik Nurmi and his wife Matilda Wilhelmiina Laine. Nurmi’s siblings, Siiri, Saara, Martti, and Lahja, were born in 1898, 1902, 1905 and 1908, respectively. In 1903, the Nurmi family moved from Raunistula into a 40-square-meter apartment in central Turku, where Paavo Nurmi would live until 1932. The young Nurmi and his friends were inspired by the English long-distance runner Alfred Shrubb. They regularly ran or walked six kilometers (four miles) to swim in Ruissalo, and back, sometimes twice a day.

By the age of eleven, Nurmi ran the 1500 meters in 5:02. Nurmi’s father Johan died in 1910 and his sister Lahja a year later. The family struggled financially, renting out their kitchen to another family and living in a single room. Nurmi, a talented student, left school to work as an errand boy for a bakery. Although he stopped running actively, he got plenty of exercise pushing heavy carts up the steep slopes in Turku. He later credited these climbs for strengthening his back and leg muscles.

Along with numerous other Finns who gained Olympic honors from 1920, Nurmi was inspired by his countryman Hannes Kolehmainen, who won three long-distance races at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. In training and in races, Nurmi carried a stopwatch so that he could precisely regulate his pace. In 1914, Nurmi joined the sports club Turun Urheiluliitto and won his first race on the 3000 meters. Two years later, he revised his training program to include walking, sprints, and calisthenics. He continued to provide for his family through his new job at the Ab. H. Ahlberg & Co workshop in Turku, where he worked until he started his military service at a machine gun company in the Pori Brigade in April 1919. During the Finnish Civil War in 1918, Nurmi remained politically passive and concentrated on his work and his Olympic ambitions. After the war, he decided not to join the newly founded Finnish Workers’ Sports Federation, but wrote articles for the federation’s chief organ and criticized the discrimination against many of his fellow workers and athletes.

In the army, Nurmi quickly impressed in the athletic competitions: While others marched, Nurmi ran the whole distances with a rifle on his shoulder and a backpack full of sand. He improvised new training methods in the army barracks; he ran behind trains, holding on to the rear bumper, to stretch his stride, and used heavy iron-clad army boots to strengthen his legs. Nurmi soon began setting personal bests and got close for the Olympic selection. In March 1920, he was promoted to corporal (alikersantti). On 29 May 1920, he set his first national record on the 3000 m and went on to win the 1500 m and the 5000 m at the Olympic trials in July. His success brought electric lighting and running water for his family in Turku. Nurmi, however, was given the scholarship to study at the Teollisuuskoulu industrial school in Helsinki.

Personal Life

Paavo Nurmi married socialite Sylvi Laaksonen in 1932, but they divorced in 1935, because she did not want their son Matti to be raised as a runner, and also claimed that Nurmi was too obsessed with athletics. Matti Nurmi did become a middle-distance runner, and later a “self-made” businessman. Nurmi’s relationship with his son was termed “uneasy”. Matti admired his father more as a businessman than as an athlete, and the two never discussed his running career. As a runner, Matti was at his best in the 3000 m, where he equalled his father’s time.

In the famous race on 11 July 1957 when the “three Olavis” (Salsola, Salonen, and Vuorisalo) broke the world record for the 1500 m, Matti Nurmi finished a distant ninth with his personal best, 2.2 seconds slower than his father’s world record from 1924. Hollywood actress Maila Nurmi, best known as the horror icon “Vampira”, was often referred to as Paavo Nurmi’s niece. However, the kinship is not supported by official documents.

Paavo Nurmi always took great care of his physical health and condition right up to the end of his life. At the age of 60, he suffered from myocardial infarction, despite the absence of the known risk factors: his blood pressure and cholesterol were both normal and he was a non-smoker and still physically active.

Career and Works

At the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, Nurmi won the 10,000-metre run and the 10,000-metre cross-country race; at the 1928 Games in Amsterdam, he took another gold medal in the 10,000-metre run. Most spectacular were his feats at the 1924 Games in Paris. In little more than one hour on July 10, an extremely hot day, he set Olympic records in the 1,500-metre and 5,000-metre runs. Two days later, again in oppressive heat, he repeated his 1920 triumph in the 10,000-metre cross-country race (an event discontinued after 1924), and the following day he finished first in an unofficial 3,000-metre team race that was won by Finland (no medals were awarded).

In 1921, Nurmi set the world record for the 10,000 m, in Stockholm, and the following year he broke the records for the 2000 m, 3000 m, and 5000 m. The year after, he set additional records for the mile and the 1500 m. He is the only runner who ever hold the records for the 5000 m, 10.000 m, and the mile at the same time. In 1923, he graduated with an engineering degree and returned to his hometown to prepare for the next Olympics.

In 1922, Nurmi broke the world records for the 2000 m, the 3000 m, and the 5000 m. A year later, Nurmi added the records for the 1500 m and the mile. His feat of holding the world records for the mile, the 5000 m and the 10,000 m at the same time has not been matched by any other athlete before or since. Nurmi also tested his speed in the 800 m, winning the 1923 Finnish Championships with a new national record. After excelling in mathematics, Nurmi graduated as an engineer in 1923 and returned home to prepare for the upcoming Olympic Games.

On August 23, 1923, in Stockholm, Nurmi consulted his stopwatch as he set his mile record, running each of the first three quarters (440 yards) in exactly 63 seconds and then the final quarter in 61.4 seconds. Despite his success, his method of evenly paced quarters was not widely imitated. In early 1925 he made a successful tour of the United States, appearing in a string of track meets.

He traveled to Paris to compete in the 1924 Summer Olympics. He easily won the 1500 m, breaking the Olympic record by three seconds. Two hours later, he earned a gold medal for the 5000 m. The 113 °F (45 °C) heat caused more than half of the cross-country competitors to abandon the race altogether. Nurmi won the race by a margin of almost a minute and a half. Later that day, he also earned the gold for the 3000 m team race.

In early 1925, Nurmi embarked on a widely publicized tour of the United States. He competed in 55 events (45 indoors) during a five-month period, starting at a sold-out Madison Square Garden on 6 January. His debut was a copy of his feats in Helsinki and Paris. Nurmi defeated Joie Ray and Lloyd Hahn to win the mile and Ritola to win the 5000 m, again setting new world records for both distances. Nurmi broke ten more indoor world records in regular events and set several new best times for rarer distances. He won 51 of the events, abandoned one race and lost two handicap races along with his final event; a half-mile race at the Yankee Stadium, where he finished second to American track star Alan Helffrich. Helffrich’s victory ended Nurmi’s 121-race, four-year win streak in individual scratch races at distances from 800 m upwards. Although he hated losing more than anything, Nurmi was the first to congratulate Helffrich. The tour made Nurmi extremely popular in the United States, and the Finn agreed to meet President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. Nurmi left America fearing that he had competed too often and burned himself out.

At the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, Nurmi participated in only three events. He won the Gold in the 10,000m and the Silver in the 5,000m and 3,000 Steeplechase. Over his illustrations career, he set 22 official world records. In his peak years, he was undefeated for a stretch of 121 races in the 800m and upward distances. In 1928 he set a world record for the one-hour run: 19,210 meters (11 miles 1,648 yards).

In 1926, Nurmi broke Wide’s world record for the 3000 m. in Berlin and then improved the record in Stockholm, despite Nils Eklöf repeatedly trying to slow his pace down in an effort to aid Wide. Nurmi was furious at the Swedes and vowed never to race Eklöf again. In October 1926, he lost a 1500 m race along with his world record to Germany’s Otto Peltzer. This marked the first time in over five years and 133 races that Nurmi had been defeated at a distance over 1000 m. In 1927, Finnish officials barred him from international competition for refusing to run against Eklöf at the Finland-Sweden international, canceling the Peltzer rematch scheduled for Vienna. Nurmi ended his season and threatened, until late November, to withdraw from the 1928 Summer Olympics.

In January 1929, Nurmi started his second U.S. tour from Brooklyn. He suffered his first-ever defeat in the mile to Ray Conger at the indoor Wanamaker Mile. Nurmi was seven seconds slower than in his world record run in 1925, and it was immediately speculated if the mile had become too short a distance for him. In 1930, he set a new world record for the 20 km. In July 1931, Nurmi showed he still had the pace for the shorter distances by beating Lauri Lehtinen, Lauri Virtanen and Volmari Iso-Hollo, and breaking the world record on the now-rare two miles. He was the first runner to complete the distance in less than nine minutes.

Less than three days before his first competition in the 1932 Los Angeles Summer Olympics, the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) barred him from participating, based on erroneous reports that he had been paid to race in events in Germany. On 26 June 1932 Nurmi started his first marathon at the Olympic trials. Not drinking a drop of liquid, he ran the old-style ‘short marathon’ of 40.2 km (25 miles) in 2:22:03.8 on the pace to finish in about 2:29:00, just under Albert Michelsen’s marathon world record of 2:29:01.8. At the time, he led Armas Toivonen, the eventual Olympic bronze medalist, by six minutes. Nurmi’s time was the new unofficial world record for the short marathon. Confident that he had done enough, Nurmi stopped and retired from the race owing to problems with his Achilles tendon. The Finnish Olympic Committee entered Nurmi for both the 10,000 m and the marathon. In August of 1934, the IAAF voted to uphold his suspension from international amateur athletics. Nurmi retired from running after winning his last 10,000 m race on September 16, 1934.

In 1933, Nurmi ran his first 1500 m. in three years and won the national title with his best time since 1926. At the IAAF meet in August 1934, Finland launched two proposals that lost. The council then brought forward its resolution empowering it to suspend athletes that it finds in violation of the IAAF amateur code. With a 12–5 vote, with many not voting, Nurmi’s suspension from international amateur athletics became definite. Less than three weeks later, Nurmi retired from running with a 10,000 m victory in Viipuri on 16 September 1934. Nurmi remained undefeated in the distance throughout his 14-year top-level career. In cross country running, his win streak lasted 19 years.

Nurmi coached runners for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. He opened a men’s clothing store in 1936, which became a tourist attraction. He also began working as a contractor, building forty apartment buildings in Helsinki. He quickly became a millionaire and eventually was among Finland’s richest people.

In February 1940, during the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union, Nurmi returned to the United States with his protégé Taisto Mäki, who had become the first man to run the 10,000 m under 30 minutes, to raise funds and rally support to the Finnish cause. The relief drive, directed by former president Herbert Hoover, included a coast-to-coast tour by Nurmi and Mäki. Hoover welcomed the two as “ambassadors of the greatest sporting nation in the world.” While in San Francisco, Nurmi received news that one of his apprentices, 1936 Olympic champion Gunnar Höckert, had been killed in action. Nurmi left for Finland in late April and later served in the Continuation War in a delivery company and as a trainer in the military staff. Before he was discharged in January 1942, Nurmi was promoted first to a staff sergeant (ylikersantti) and later to a sergeant first class (vääpeli).

When Helsinki’s turn came in 1952 to host the Olympics, the 55-year-old Paavo Nurmi entered the stadium bearing the Olympic torch with the same old spring in his step. Competitors from 70 countries broke ranks spontaneously and rushed over to applaud their idol -the man who had come to epitomize the endurance, will-power, and self-discipline that all aspiring athletes strive for. Urho Kekkonen, the former Finnish president and Paavo Nurmi’s close friend and contemporary as an international athlete (in the high jump), once said that the key element behind Nurmi’s exceptional achievements was his character. In truth, he was determined to the point of being stubborn, relentless and even merciless. He also had a good brain to devise his own training programmes, the courage to set his sights high, and the strength of mind to stay focused on his goals until he achieved them.

Nurmi ran for the last time on 18 February 1966 at the Madison Square Garden, invited by the New York Athletic Club. In 1962, Nurmi predicted that welfare countries would start to struggle in the distance events: “The higher the standard of living in a country, the weaker the results often are in the events which call for work and trouble. I would like to warn this new generation: ‘Do not let this comfortable life make you lazy. Do not let the new means of transport kill your instinct for physical exercise. Too many young people get used to driving in a car even for small distances.'” In 1966, he took the microphone in front of 300 sports club guests and criticized the state of distance running in Finland, reproaching the sports executives as publicity seekers and tourists, and demanding athletes sacrifice everything to accomplish something. Nurmi lived to see the renaissance of Finnish running in the 1970s, led by athletes such as the 1972 Olympic gold medalists Lasse Virén and Pekka Vasala. He had complimented the running style of Virén and advised Vasala to concentrate on Kipchoge Keino.

As in sports training where he ultimately only ever trusted his own judgment and experience, in business life, too, he proved to be a determinedly independent man. Although Nurmi’s business interests widened over the years, building activities always retained a central role, bringing him wealth and yet further success.

Awards and Honor

Along with Kolehmainen, Nurmi had the honor of lighting the Olympic flame to open the 1952 Games in Helsinki, Finland. Nurmi was depicted in national currency on the 10 markkaa banknote from 1986 until 2002 when Finland adopted the euro.

Death and Legacy

Ten years on he suffered a stroke, and Nurmi died from multiple complications of atherosclerosis on October 1, 1973, at the age of 76, in Helsinki and was given a state funeral. Kekkonen attended the funeral and praised Nurmi: “People explore the horizons for a successor. But none comes and none will, for his class is extinguished with him.” At the request of Nurmi, who enjoyed classical music and played the violin, Konsta Jylhä’s Vaiennut viulu (The Silenced Violin) was played during the ceremony. Nurmi’s last record fell in 1996; his 1925 world record for the indoor 2000 m lasted as the Finnish national record for 71 years.

In his 15 year career, Nurmi never lost in the 10,000m or cross country events. He is, without a doubt, the most successful distance runner of the 20th century. From being a hard-working employee, Paavo Nurmi has gone on to become one of the most admired sportsmen in history.

Nurmi broke 22 official world records on distances between 1500 m and 20 km; a record in running. He also set many more unofficial ones for a total of 58. His indoor world records were all unofficial as the IAAF did not ratify indoor records until the 1980s. Nurmi’s record for most Olympic gold medals was matched by gymnast Larisa Latynina in 1964, swimmer Mark Spitz in 1972 and fellow track and field athlete Carl Lewis in 1996, and broken by swimmer Michael Phelps in 2008. Nurmi’s record for most medals in the Olympic Games stood until Edoardo Mangiarotti won his 13th medal in fencing in 1960. Time selected Nurmi as the greatest Olympian of all time in 1996, and IAAF named him among the first twelve athletes to be inducted into the IAAF Hall of Fame in 2012.

In 1997, a historic stadium in Turku has renamed the Paavo Nurmi Stadium. Twenty world records have been set at the stadium, including John Landy’s records on the 1500 m and the mile, Nurmi’s record on the 3000 m and Zátopek’s record on the 10,000 m. In fiction, Nurmi appears in William Goldman’s 1974 novel Marathon Man as the idol of the protagonist, who aims to become a greater runner than Nurmi. The opera on Nurmi, Paavo the Great. Great Race. Great Dream., written by Paavo Haavikko and composed by Tuomas Kantelinen, debuted at the Helsinki Olympic Stadium in 2000. In a 2005 episode of The Simpsons, Mr. Burns brags that he once outraced Nurmi in his antique motorcar.

Information Source: