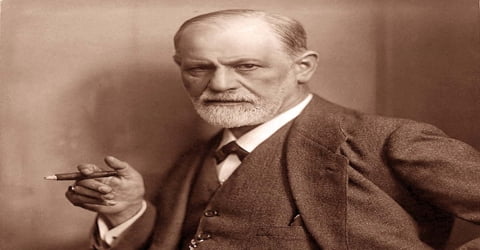

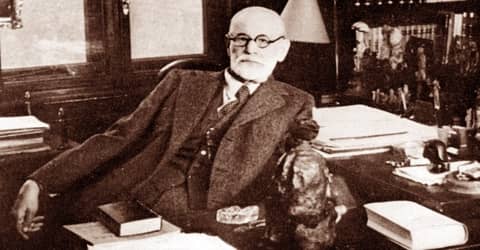

Biography of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud – Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis.

Name: Sigismund Schlomo Freud

Date of Birth: 6 May 1856

Place of Birth: Freiberg in Mähren, Moravia, Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic)

Date of Death: 23 September 1939 (aged 83)

Place of Death: Hampstead, London, United Kingdom

Spouse: Martha Bernays (m. 1886–1939, his death)

Children: Anna Freud, Ernst L. Freud, Martin Freud, Mathilde Freud, Oliver Freud, Sophie Freud

Fields: Neurology, psychotherapy, psychoanalysis

Early Life

Sigismund Schlomo Freud was one of the most influential scientists in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. He was born on May 6, 1856, Freiberg, Moravia, Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic).

Freud was born to Galician Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire. He qualified as a doctor of medicine in 1881 at the University of Vienna. Upon completing his habilitation in 1885, he was appointed a docent in neuropathology and became an affiliated professor in 1902. Freud lived and worked in Vienna, having set up his clinical practice there in 1886. In 1938 Freud left Austria to escape the Nazis. He died in exile in the United Kingdom in 1939.

Early in his career, Freud became greatly influenced by the work of his friend and Viennese colleague, Josef Breuer, who had discovered that when he encouraged a hysterical patient to talk uninhibitedly about the earliest occurrences of the symptoms, the symptoms sometimes gradually abated.

After much work together, Breuer ended the relationship, feeling that Freud placed too much emphasis on the sexual origins of a patient’s neuroses and was completely unwilling to consider other viewpoints. Meanwhile, Freud continued to refine his own argument.

Freud may justly be called the most influential intellectual legislator of his age. His creation of psychoanalysis was at once a theory of the human psyche, a therapy for the relief of its ills, and an optic for the interpretation of culture and society. Despite repeated criticisms, attempted refutations, and qualifications of Freud’s work, its spell remained powerful well after his death and in fields far removed from psychology as it is narrowly defined. If, as the American sociologist Philip Rieff once contended, “psychological man” replaced such earlier notions as political, religious, or economic man as the 20th century’s dominant self-image, it is in no small measure due to the power of Freud’s vision and the seeming inexhaustibility of the intellectual legacy he left behind.

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. He believed that smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it. Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually suffering buccal cancer. Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, “the one great habit.”

Though in overall decline as a diagnostic and clinical practice, psychoanalysis remains influential within psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy, and across the humanities. It thus continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate with regard to its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or is detrimental to the feminist cause. Nonetheless, Freud’s work has suffused contemporary Western thought and popular culture. In the words of W. H. Auden’s 1940 poetic tribute, by the time of Freud’s death, he had become “a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives.”

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Sigmund Freud was born in the Austrian town of Freiberg, now known as the Czech Republic, on May 6, 1856. Freud was born to Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire (later Příbor, Czech Republic), the first of eight children. Both of his parents were from Galicia, in modern-day Ukraine. His father, Jakob Freud (1815–1896), a wool merchant, had two sons, Emanuel (1833–1914) and Philipp (1836–1911), by his first marriage. Jakob’s family were Hasidic Jews, and although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study. He and Freud’s mother, Amalia Nathansohn, who was 20 years younger and his third wife, were married by Rabbi Isaac Noah Mannheimer on 29 July 1855. They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith’s house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born. He was born with a caul, which his mother saw as a positive omen for the boy’s future.

In 1859 the Freud family was compelled for economic reasons to move to Leipzig and then a year after to Vienna, where Freud remained until the Nazi annexation of Austria 78 years later.

Freud’s half-brothers emigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the “inseparable” playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel’s son, John. Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud’s sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born: Rosa (b. 1860), Marie (b. 1861), Adolfine (b. 1862), Paula (b. 1864), Alexander (b. 1866). In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved to be an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors. He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin, and Greek.

In 1873 Freud was graduated from the Sperl Gymnasium and, apparently inspired by a public reading of an essay by Goethe on nature, turned to medicine as a career. At the University of Vienna, he worked with one of the leading physiologists of his day, Ernst von Brücke, an exponent of the materialist, anti-vitalist science of Hermann von Helmholtz.

He received his medical degree in 1881. As a medical student and young researcher, Freud’s research focused on neurobiology, exploring the biology of brains and nervous tissue of humans and animals.

Personal Life

In 1886 Freud married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg. They had six children: Mathilde (b. 1887), Jean-Martin (b. 1889), Oliver (b. 1891), Ernst (b. 1892), Sophie (b. 1893), and Anna (b. 1895). From 1891 until they left Vienna in 1938, Freud and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19, near Innere Stadt, a historical district of Vienna.

(Photo of Sigmund Freud and Anna Freud, 1913)

The youngest of whom, Anna Freud, went on to become a distinguished psychoanalyst herself.

In 1896, Minna Bernays, Martha Freud’s sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé. The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumors, started by Carl Jung, of an affair. The discovery of a Swiss hotel log of 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst traveling with his sister-in-law, has been presented as evidence of the affair.

Career and Works

In 1873, Freud entered the University of Vienna medical school. In 1882, he became a clinical assistant at the General Hospital in Vienna and trained with psychiatrist Theodor Meynert and Hermann Nothnagel, a professor of internal medicine. By 1885, Freud had completed important research on the brain’s medulla and was appointed a lecturer in neuropathology.

After graduation, Freud promptly set up a private practice and began treating various psychological disorders. Considering himself first and foremost a scientist, rather than a doctor, he endeavored to understand the journey of human knowledge and experience.

Freud’s scientific training remained of cardinal importance in his work, or at least in his own conception of it. In such writings as his “Entwurf Einer Psychologie” (written 1895, published 1950; “Project for a Scientific Psychology”) he affirmed his intention to find a physiological and materialist basis for his theories of the psyche. Here a mechanistic neurophysiological model vied with a more organismic, phylogenetic one in ways that demonstrate Freud’s complicated debt to the science of his day.

Freud’s friend, Josef Breuer, a physician and physiologist, had a large impact on the course of Freud’s career. Breuer told his friend about using hypnosis to cure a patient, Bertha Pappenheim (referred to as Anna O.), of what was then called hysteria. Breuer would hypnotize her, and she was able to talk about things she could not remember in a conscious state. Her symptoms were relieved afterward. This became known as the “talking cure.” Freud then traveled to Paris to study further under Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist famous for using hypnosis to treat hysteria.

“The talking cure” or “chimney sweeping,” as Breuer and Anna O., respectively, called it, seemed to act cathartically to produce an abreaction, or discharge, of the pent-up emotional blockage at the root of the pathological behavior.

In 1882, Freud began his medical career at the Vienna General Hospital. His research work in cerebral anatomy led to the publication of an influential paper on the palliative effects of cocaine in 1884 and his work on aphasia would form the basis of his first book On the Aphasias: a Critical Study, published in 1891. In 1886, Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in “nervous disorders”.

Shortly after his marriage, Freud began his closest friends, with the Berlin physician Wilhelm Fliess, whose role in the development of psychoanalysis has occasioned widespread debate. Throughout the 15 years of their intimacy, Fliess provided Freud an invaluable interlocutor for his most daring ideas. Freud’s belief in human bisexuality, his idea of erotogenic zones on the body, and perhaps even his imputation of sexuality to infants may well have been stimulated by their friendship.

In 1896, Freud coined the term psychoanalysis. This is the treatment of mental disorders, emphasizing on the unconscious mental processes. It is also called “depth psychology.”

Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection. Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874). Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept. Freud owned and made use of Charles Darwin’s major evolutionary writings, and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann’s The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). Other texts of importance to Freud were by Fechner and Herbart with the latter’s Psychology as Science arguably considered to be of underrated significance in this respect. Freud also drew on the work of Theodor Lipps who was one of the main contemporary theorists of the concepts of the unconscious and empathy.

Freud also developed what he thought of as the three agencies of the human personality, called the id, ego and superego. The id is the primitive instincts, such as sex and aggression. The ego is the “self” part of the personality that interacts with the world in which the person lives. The superego is the part of the personality that is ethical and creates the moral standards for the ego.

In 1900, Freud broke ground in psychology by publishing his book “The Interpretation of Dreams.” In his book, Freud named the mind’s energy libido and said that the libido needed to be discharged to ensure pleasure and prevent pain. If it wasn’t released physically, the mind’s energy would be discharged through dreams.

The book explained Freud’s belief that dreams were simply wished fulfillment and that the analysis of dreams could lead to treatment for neurosis. He concluded that there were two parts to a dream. The “manifest content” was the obvious sight and sounds in the dream and the “latent content” was the dream’s hidden meaning.

“The Interpretation of Dreams” took two years to write. He only made $209 from the book, and it took eight years to sell 600 copies.

In 1901, he published “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life,” which gave life to the saying “Freudian slip.” Freud theorized that forgetfulness or slips of the tongue are not accidental. They are caused by the “dynamic unconscious” and reveal something meaningful about the person.

In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its “polymorphous perverse” forms and the functioning of the “drives”, to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity. The same year he published ‘Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (Dora)’ which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.

Freud is often joked about for his propensity to assign everything with sexual meaning. A likely apocryphal story is that, when someone suggested that the cigars he smoked were phallic symbols, Freud reportedly said, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” Some have called this “Freud’s ultimate anti-Freudian joke.” However, there is no written record that this quote actually came from Freud, according to Alan C. Elms in a paper published in 2001 in the Annual of Psychoanalysis.

Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories. Some patients known by pseudonyms were Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945); Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser); Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss); Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich); Fräulein Lucy R.; Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973); Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer, 1878–1914); Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild, 1878–1920); and Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff, 1887–1979). Other famous patients included Prince Pedro Augusto of Brazil (1866-1934); H.D. (1886–1961); Emma Eckstein (1865–1924); Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation; Princess Marie Bonaparte; Edith Banfield Jackson (1895–1977); and Albert Hirst (1887–1974).

In January 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany, and Freud’s books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud remarked to Ernest Jones: “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages, they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.” Freud continued to underestimate the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938, in which Nazi Germany annexed Austria and the outbreaks of violent anti-Semitism that ensued. The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938. Freud’s grandson Ernst Halberstadt and Freud’s son Martin’s wife and children left for Paris in April. Freud’s sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud’s daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.

His books were among the first to be burned, as the fruits of a “Jewish science,” when the Nazis took over Germany. Although psychotherapy was not banned in the Third Reich, where Field Marshall Hermann Göring’s cousin headed an official institute, psychoanalysis essentially went into exile, most notably to North America and England. He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and in English the following year and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis which was published posthumously.

Awards and Honor

- Goethe Prize (1930)

- Foreign Member of the Royal Society

Death and Legacy

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. Freud initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed.

Freud died in England on September 23, 1939, at age 83 by suicide. He had requested a lethal dose of morphine from his doctor, following a long and painful battle with oral cancer.

Three days after his death Freud’s body was cremated at the Golders Green Crematorium in North London, with Harrods acting as funeral directors, on the instructions of his son, Ernst. Funeral orations were given by Ernest Jones and the Austrian author Stefan Zweig. Freud’s ashes were later placed in the crematorium’s Ernest George Columbarium. They rest on a plinth designed by his son, Ernst, in a sealed ancient Greek krater painted with Dionysian scenes that Freud had received as a gift from Princess Bonaparte and which he had kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After his wife, Martha, died in 1951, her ashes were also placed in the urn.

The poem “In Memory of Sigmund Freud” was published by British poet W. H. Auden in his 1940 collection Another Time.

Literary critic Harold Bloom has been influenced by Freud. Camille Paglia has also been influenced by Freud, whom she calls “Nietzsche’s heir” and one of the greatest sexual psychologists in literature, but has rejected the scientific status of his work in her Sexual Personae (1990), writing, “Freud has no rivals among his successors because they think he wrote science, when in fact he wrote art.”

Information Source: