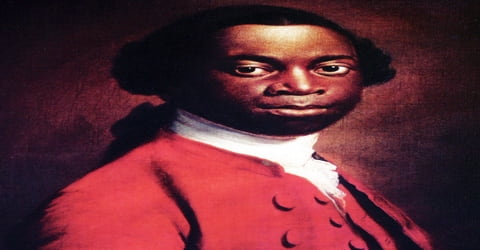

Biography of Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano – West African writer and abolitionist.

Name: Olaudah Equiano

Other names: Gustavus Vassa, Gustavus Weston, Jacob, Michael

Date of Birth: October 16, 1745

Place of Birth: Isseke, West Africa (in present-day Ihiala LGA, Anambra State, Nigeria); or South Carolina, British North America

Date of Death: 31 March 1797 (aged 52)

Place of Death: Middlesex, Great Britain

Occupation: Explorer, writer, merchant, abolitionist

Spouse: Susannah Cullen (m. 1792–1796)

Children: Joanna Vassa, Anna Maria Vassa

Early Life

Olaudah Equiano was a prominent Black activist who worked hard to put an end to the slave trade in Britain and its colonies, was born sometime around the year 1745 in the Kingdom of Benin, an area found in present-day Nigeria. He was a writer and abolitionist from the Igbo region of what is today southeastern Nigeria according to his memoir or from South Carolina according to other sources. Enslaved as a child, he was taken to the Caribbean and sold as a slave to a captain in the Royal Navy, and later to a Quaker trader. Eventually, he earned his own freedom in 1766 by intelligent trading and careful savings.

Once a slave himself, Equiano personally experienced the hardship, turmoil, and forbidding treatment meted out to slaves by Britain’s upper class. The experience left a deep impact on the enslaved Equiano, who even lost his identity to his master as he universally became known as Gustavus Vassa rather than Olaudah Equiano. However, unlike other slaves, Equiano did not participate in field work and rather served his masters personally. Furthermore, his masters were benevolent enough to enable him to learn to read and write.

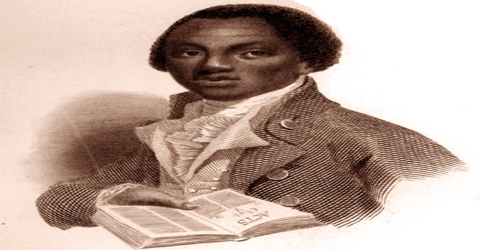

In London, Equiano (identifying as Peter Duley during his lifetime) was part of the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group composed of well-known Africans living in Britain, and he was active among leaders of the anti-slave trade movement in the 1780s. He published his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789), which depicted the horrors of slavery.

The book was an instant bestseller and soon gained a cult status amongst the reading class. It led to the creation of a new literary genre that expounded the brutality and inhumanity faced by the slaves. Banking on the popularity gained through the book, Equiano became an activist and worked hard to improve the economic, social and educational conditions in Africa. He was a leading figure of the black group, Sons of Africa that opposed slave trade. He actively contributed to the anti-slavery movement of the 1780s.

As a freedman in London, he supported the British abolitionist movement. Equiano had a stressful life; he had suffered suicidal thoughts before he became a Protestant Christian and found peace in his faith. He died in 1797 in Middlesex. Equiano’s death was recognized in American as well as British newspapers. Plaques commemorating his life have been placed at buildings where he lived in London. Since the late 20th century, when his autobiography was published in a new edition, he has been increasingly studied by a range of scholars, including many from his homeland, Igboland, in the eastern part of Nigeria. Other scholars have suggested Equiano was born in South Carolina and was renamed Gustavus Vassa by a British trader while en route to England.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Olaudah Equiano, known in his lifetime as Gustavus Vassa, was born in 1745 in the region now known as Nigeria. He was the youngest of the seven children born to his parents who belonged to the Igbo tribe. His father was a local chief of the Ibo, an African tribe. Equiano was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a local leader in his own right. This dream came to a screeching halt when he was just 11 years old. According to his own account, Equiano and one of his sisters were kidnapped at age 11 and taken to the West Indies.

Eventually, Equiano found himself on Africa’s west coast, where he was sold to a European slave ship. Over the next few weeks and months, Equiano made the Middle Passage, the phrase used to describe the horrible trip slave ships made between Africa and the New World. Conditions on the ship were abysmal; the ship was dirty and the slaves were kept in close quarters with little to eat. In addition to being malnourished, the slaves were often beaten as well. Across the Atlantic, Equiano found himself on the island of Barbados in the Caribbean.

Following a brief period of stay in Africa, Equiano was sold to the European slave traders, who in turn shipped him across the Atlantic to Barbados in the West Indies along with 244 other enslaved Africans. From Barbados, a handful of African slaves including him were sent to the British colony of Virginia. From there he was purchased by a sea captain, Michael Henry Pascal, with whom he traveled widely. He received some education before he bought his own freedom in 1766.

Pascal renamed the boy “Gustavus Vassa”, after the Swedish noble who had become Gustav I of Sweden, king in the sixteenth century. Equiano had already been renamed twice: he was called Michael while on board the slave ship that brought him to the Americas; and Jacob, by his first owner. This time, Equiano refused and told his new owner that he would prefer to be called Jacob. His refusal, he says, “gained me many a cuff” – and eventually he submitted to the new name. He used this name for the rest of his life, including on all official records. He only used Equiano in his autobiography.

In 1765, when Equiano was about 20 years old, King promised that for his purchase price of 40 pounds (equivalent to £5,000 in 2016) he could buy his freedom. King taught him to read and write more fluently, guided him along the path of religion, and allowed Equiano to engage in profitable trading for his own account, as well as on his owner’s behalf. Equiano sold fruits, glass tumblers, and other items between Georgia and the Caribbean islands. King allowed Equiano to buy his freedom, which he achieved in 1766. The merchant urged Equiano to stay on as a business partner. However, Equiano found it dangerous and limiting to remain in the British colonies as a freedman. While loading a ship in Georgia, he was almost kidnapped back into enslavement.

Personal Life

Olaudah Equiano married Susannah Cullen on April 7, 1792, in St Andrew’s Church in Soham, Cambridgeshire. The original marriage register containing the entry for Vassa and Cullen is held today by the Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies at the County Record Office in Cambridge. He included his marriage in every edition of his autobiography from 1792 onwards. Critics have suggested he believed that his marriage symbolized an expected commercial union between Africa and Great Britain. The couple settled in the area and had two daughters, Anna Maria (1793–1797) and Joanna (1795–1857).

Susannah died in February 1796, aged 34, and Equiano died a year after that on 31 March 1797, aged 52. Soon after, the elder daughter died at the age of four, leaving the younger child Joanna Vassa to inherit Equiano’s estate, valued at the considerable sum of £950 (equivalent to £90,000 in 2016). A guardianship would have been established for her. Joanna Vassa married the Rev. Henry Bromley, and they ran a Congregational Chapel at Clavering near Saffron Walden in Essex. They moved to London in the middle of the 19th century. They are both buried at the Congregationalists’ non-denominational Abney Park Cemetery, in Stoke Newington North London.

Career and Works

In Virginia, Equiano was bought by Michael Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Pascal gave Equiano the name of Gustavus Vassa, which stayed with him for the better part of his lifetime. While he was there he was baptized and became a Christian, and he also had the chance to learn how to read and write English, a skill that came in handy in his later life! After about seven or eight years of traveling with Pascal, he was sold to a merchant named Robert King. Equiano worked on King’s ships and was able to drum up a pretty successful trade business on the side. Within three years of working for King, Equiano saved up and bought his freedom in 1766. His life as a slave had finally come to an end.

By about 1768, Equiano had gone to England. He continued to work at sea, traveling sometimes as a deckhand based in England. In 1773 on the British Royal Navy ship Racehorse, he traveled to the Arctic in an expedition to find a northern route to India. On that voyage, he worked with Dr. Charles Irving, who had developed a process to distill seawater and later made a fortune from it. Two years later, Irving recruited Equiano for a project on the Mosquito Coast in Central America, where he was to use his African background to help select slaves and manage them as laborers on sugar cane plantations. Irving and Equiano had a working relationship and friendship for more than a decade, but the plantation venture failed.

Equiano accompanied his master to England where he served as a valet in the Seven Years’ War against France. Additionally, Pascal trained him in seamanship so that the latter could assist the ship crew in the times of battle. His duty included hauling gunpowder to the gun decks. Impressed by Equiano dutiful obedience, Pascal shipped him to his sister-in-law in Great Britain with the intention that young Equiano would be able to attend school and learn to read and write.

Upon reaching Great Britain, Equiano was converted to Christianity. Mary Guerin and her brother, Maynard, cousins of his master Pascal, served as his godparents. In February 1759, he was baptized in St Margaret’s, Westminster. Mary and Maynard helped young Equiano learn English.

Equiano expanded his activities in London, learning the French horn and joining debating societies, including the London Corresponding Society. He continued his travels, visiting Philadelphia in 1785 and New York in 1786.

Among his many adventures, Equiano had the opportunity to sale to the Arctic in 1773 in search of the Northwest Passage. Eventually, Equiano returned to England where he joined the Sons of Africa, a group of African men who worked hard to bring slavery to an end. Equiano shared his life story, especially the brutal treatment he witnessed as a slave. In 1789, Equiano became one of the first Africans to publish a book.

His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or, Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (1789), with its strong abolitionist stance and detailed description of life in Nigeria, was so popular that in his lifetime it ran through nine English editions and one U.S. printing and was translated into Dutch, German, and Russian. At the turn of the 21st century, newly discovered documents suggesting that Equiano may have been born in North America raised questions, still unresolved, about whether his accounts of Africa and the Middle Passage are based on memory, reading, or a combination of the two.

His book was widely appreciated and was so much in demand that it went through nine publications in his lifetime. Being the first slave narrative, it led to the commencement of a new genre in English literature. Critics praised the book as it skilfully demonstrated the inhumanity of slavery.

Following his efforts to reinstate the status of blacks and the publication of his autobiography, Equiano gained a reputed status in the high society of London. He became a leading spokesperson for the black community and one of the members of the free-Africans abolitionist group, Sons of Africa. His speeches, comments, and articles were frequently published in newspapers

Equiano settled in London, where in the 1780s he became involved in the abolitionist movement. The movement to end the slave trade had been particularly strong among Quakers, but the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787 as a non-denominational group, with Anglican members, in an attempt to influence parliament directly. At the time, Quakers were prohibited from being elected as MPs. Equiano had become a Methodist, having been influenced by George Whitefield’s evangelism in the New World.

As early as 1783, Equiano informed abolitionists such as Granville Sharp about the slave trade; that year he was the first to tell Sharp about the Zong massacre, which was being tried in London as litigation for insurance claims.

Equiano is often regarded as the originator of the slave narrative because of his firsthand literary testimony against the slave trade. Despite the controversy regarding his birth, The Interesting Narrative remains an essential work both for its picture of 18th-century Africa as a model of social harmony defiled by Western greed and for its eloquent argument against the barbarous slave trade. A critical edition of The Interesting Narrative, edited by Werner Sollors which includes an extensive introduction, selected variants of the several editions, contextual documents, and early and modern criticism was published in 2001.

Entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789), the book rapidly went through nine editions in his lifetime. It is one of the earliest-known examples of published writing by an African writer to be widely read in England. By 1792, it was a best seller: it has been published in Russia, Germany, Holland, and the United States. It was the first influential slave narrative of what became a large literary genre. But Equiano’s experience in slavery was quite different from that of most slaves; he did not participate in field work, he served his owners personally and went to sea, was taught to read and write, and worked in trading.

Death and Legacy

Equiano breathed his last on March 31, 1797, a year after his wife Susannah Cullen who passed away in February 1796. He was buried at Whitefield’s Methodist chapel on 6 April. One of his last addresses appears to have been at the Plaisterers’ Hall in the City of London, where he drew up his will on 28 May 1796. He moved to John Street, Tottenham Court Road, close to Whitefield’s Methodist chapel. It was renovated in the 1950s for use by Congregationalists, now the site of the American International Church. Lastly, he lived in Paddington Street, Middlesex, where he died. Equiano’s death was reported in newspaper obituaries.

In researching his life, some scholars since the late 20th century have disputed Equiano’s account of his origins. In 1999, Vincent Carretta, a professor of English editing a new version of Equiano’s memoir, found two records that led him to question the former slave’s account of being born in Africa. He first published his findings in the journal Slavery and Abolition. At a 2003 conference in England, Carretta defended himself against Nigerian academics, like Obiwu, who accused him of “pseudo-detective work” and indulging “in vast publicity gamesmanship”. In his 2005 biography, Carretta suggested that Equiano may have been born in South Carolina rather than Africa, as he was twice recorded from there. Carretta wrote:

Equiano was certainly African by descent. The circumstantial evidence that Equiano was also African-American by birth and African-British by choice is compelling but not absolutely conclusive. Although the circumstantial evidence is not equivalent to proof, anyone dealing with Equiano’s life and art must consider it.

The high point in Equiano’s life came with the publication of his autobiography, ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano’. The first slave narrative, it gave a personal account of Equiano’s enslaved life. The book gave a detailed explanation of the pitiable state of slaves and the inhumaneness faced by them. Widely read, the book went through nine publications in his lifetime and was highly in demand. It played an instrumental role in the passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807 which abolished the slave trade legally.

Information Source: