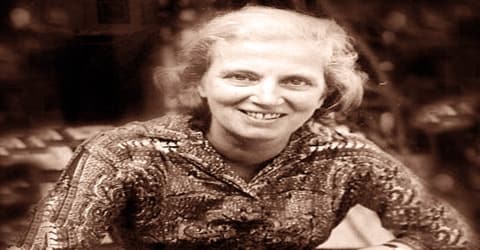

Biography of Nadia Boulanger

Nadia Boulanger – French composer, conductor, and teacher.

Name: Juliette Nadia Boulanger

Date of Birth: September 16, 1887

Place of Birth: 9th arrondissement of Paris, Paris, France

Date of Death: October 22, 1979 (age 92)

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Composer, Conductor, and Teacher

Father: Ernest Boulanger

Mother: Raissa Myshetskaya

Early Life

A French composer, conductor, and one of the most influential teachers of musical composition of the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger was born in Paris on 16 September 1887, to French composer and pianist Ernest Boulanger (1815-1900) and his wife Raissa Myshetskaya (1856-1935), a Russian princess, who descended from St. Mikhail Tchernigovsky. From a musical family, she achieved early honors as a student at the Paris Conservatoire but, believing that she had no particular talent as a composer, she gave up writing music and became a teacher. In that capacity, she influenced generations of young composers, especially those from the United States and other English-speaking countries.

It might come as a surprise that as a little girl Nadia found music repulsive as she was surrounded by music all day long! Gradually she overcame her repulsion and realized her talent for all things musical. She received lessons from some great teachers which helped to polish her natural skills. Her father was a renowned composer and the family lived comfortably. However, when her father died, the responsibility of providing for her mother and sister fell upon young Nadia’s shoulders and she took to teaching music to earn a livelihood. She was a keen composer and a highly skilled pianist. She became very popular playing in concerts which also added to her stance as a music teacher. She lived in an era marked by political turmoil and unrest. A kind-hearted soul, she organized a charity along with her sister to help those affected by the war even as she juggled her busy career.

Among her students were those who became leading composers, soloists, arrangers, and conductors, including Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Virgil Thomson, Darius Milhaud, Elliott Carter, David Diamond, Dinu Lipatti, Igor Markevitch, İdil Biret, Daniel Barenboim, John Eliot Gardiner, Philip Glass, Lalo Schifrin, Astor Piazzolla, Quincy Jones, and Michel Legrand. Her female students, whose chances in the 20th century for recognition were significantly lower than that of the men, including notable American women composers, such as Louise Talma, Elaine Bearer, Eugenie Kuffler, Elise Grant Cieslak, and Anne Robertson.

Nadia Boulanger was the first woman to conduct many major orchestras in America and Europe, including the BBC Symphony, Boston Symphony, Hallé, New York Philharmonic and Philadelphia orchestras. She conducted several world premieres, including works by Copland and Stravinsky.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Nadia Boulanger was born as Juliette Nadia Boulanger on September 16, 1887, in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, Paris, France, to Ernest Boulanger and his wife Raissa Myshetskaya. Ernest was a renowned composer and pianist who himself came from a family of famous musicians. She had one younger sister. Both her parents were musically very active and little Nadia was irritated with music playing around her all day long. However, her attitude towards music changed when she was five and she began displaying her inherent musical talents.

Her sister, named Marie-Juliette Olga but known as Lili, was born in 1893 when Nadia was six. When Ernest brought Nadia home from their friends’ house, before she was allowed to see her mother or Lili, he made her promise solemnly to be responsible for the new baby’s welfare. He urged her to take part in her sister’s care. From the age of seven, Nadia studied hard in preparation for her Conservatoire entrance exams, sitting in on their classes and having private lessons with its teachers. Lili often stayed in the room for these lessons, sitting quietly and listening.

Nadia began receiving musical lessons and joined the Conservatoire in 1896 when she was nine. She also took private lessons from Vierne and Guilmant. Her elderly father died in 1900 leaving behind a young wife and two daughters to fend for themselves. Her mother lived an extravagant lifestyle and thus Boulanger was determined to study well so that she could support her mother and little sister. Even as a student she began giving organ and piano performances and earned money. She studied composition under Faure.

Personal Life

Nadia Boulanger was born into a family of great musicians and thus music was a passion she shared with her younger sister, Lili. The sisters were very close and Nadia deeply loved and admired Lili who unfortunately died young. She lived a long and productive life over the course of which she tutored several pupils of whom many became her good friends. She was highly revered and loved by her students.

Her eyesight and hearing began to fade toward the end of her life. On August 13, 1977, in advance of her 90th birthday, Nadia was given a surprise birthday celebration at Fontainebleau’s English Garden. The school’s chef had prepared a large cake, on which was inscribed: “1887-Happy Birthday to you, Nadia Boulanger-Fontainebleau, 1977”. When the cake was served, 90 small white candles floating on the pond illuminated the area. Boulanger’s then-protégé, Emile Naoumoff, performed a piece he had composed for the occasion.

Career and Works

Nadia Boulanger received her formal training there in 1897-1904, studying composition with Gabriel Fauré and organ with Charles-Marie Widor. She later taught composition at the conservatory and privately. She also published a few short works and in 1908 won second place in the Prix de Rome competition with her cantata La Sirène. She ceased composing, rating her works “useless,” after the death in 1918 of her talented sister Lili Boulanger, also a composer.

In 1907 Nadia progressed to the final round but again did not win. In late 1907 she was appointed to teach elementary piano and accompagnement au piano at the newly created Conservatoire Femina-Musica. She was also appointed as assistant to Henri Dallier, the professor of harmony at the Conservatoire. In the 1908 Prix de Rome competition, Nadia Boulanger caused a stir by submitting an instrumental fugue rather than the required vocal fugue. The subject was taken up by the national and international newspapers and was resolved only when the French Minister of Public Information decreed that Boulanger’s work is judged on its musical merit alone. She won the Second Grand Prix for her cantata, La Sirène.

Nadia began performing piano duets with Pugno and in 1908 the two composed a song cycle, ‘Les Heures Claires’ which was well received by the public. Still hoping for a Grand Prix de Rome, Boulanger entered the 1909 competition but failed to win a place in the final round. Later that year, her sister Lili, then sixteen, announced to the family her intention to become a composer and win the Prix de Rome herself.

In 1910, Annette Dieudonné became a student of Boulanger’s, continuing with her for the next fourteen years. When her studies ended, she began teaching Boulanger’s students the rudiments of music and solfège. She was Boulanger’s close friend and assistant for the rest of her life. Boulanger attended the premiere of Diaghilev’s ballet The Firebird in Paris, with music by Stravinsky. She immediately recognized the young composer’s genius and began a lifelong friendship with him. Nadia made her debut as a conductor in 1912 and led the Société des Matinées Musicales orchestra where she also performed as a soloist.

The 1910s was a period marked by political unrest and wars. Due to the war, public programs were reduced and Boulanger had to put her performing career on hold. She continued her work as a teacher. Her younger sister Lili was deeply involved in war work and inspired by her she too joined her. Working together the two sisters created a charity that supplied food, clothing, and money to soldiers who had been musicians before the war.

In 1919, Nadia Boulanger performed in more than twenty concerts, often programming her own music and that of her sister. Since the Conservatoire Femina-Musica had closed during the war, Alfred Cortot and Auguste Mangeot founded a new music school in Paris, which opened later that year, the École Normale de musique de Paris. Boulanger was invited by Cortot to join the school, where she ended up teaching classes in harmony, counterpoint, musical analysis, organ, and composition. In 1920, Boulanger began to compose again, writing a series of songs to words by Camille Mauclair.

In 1921 Nadia Boulanger began her long association with the American Conservatory, founded after World War I at Fontainebleau by the conductor Walter Damrosch for American musicians. She was the organist for the premiere (1925) of the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra by Aaron Copland, her first American pupil, and appeared as the first woman conductor of the Boston, New York Philharmonic, and Philadelphia orchestras in 1938. She had already become (1937) the first woman to conduct an entire program of the Royal Philharmonic in London.

In 1921, Boulanger performed at two concerts in support of women’s rights, at both of which music by Lili was programmed. Later in life, she claimed never to have been involved with feminism, and that women should not have the right to vote as they “lacked the necessary political sophistication.” The French Music School for Americans opened in 1921 and she joined the program as a professor of harmony. By now she had a very hectic schedule that comprised teaching, performing and composing. She decided to focus more on the teaching job as it paid better than the others and she needed the money to take care of her mother and herself.

The New York Symphony Society along with Walter Damrosch and others arranged for her to tour the U.S. in 1924. She played solo organ pieces written by Lili and premiered Copland’s new Symphony for Organ and Orchestra. She returned to France in 1925. Nadia resumed conducting during the mid-1930s and made her Paris debut with the orchestra of the Ecole Normale in a programme of Mozart, Bach, and Jean Francaix. She also continued with her private classes.

Gershwin visited Nadia Boulanger in 1927, asking for lessons in composition. They spoke for half an hour after which Boulanger announced, “I can teach you nothing.” Taking this as a compliment, Gershwin repeated the story many times. The Great Depression increased social tensions in France. Days after the Stavisky riots in February 1934, and in the midst of a general strike, Boulanger resumed conducting. She made her Paris debut with the orchestra of the École Normale in a programme of Mozart, Bach, and Jean Françaix. Boulanger’s private classes continued; Elliott Carter recalled that students who did not dare to cross Paris through the riots showed only that they did not “take music seriously enough”. By the end of the year, she was conducting the Orchestre Philharmonique de Paris in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with a programme of Bach, Monteverdi, and Schütz. Her mother Raissa died in March 1935, after a long decline. This freed Boulanger from some of her ties to Paris, which had prevented her from taking up teaching opportunities in the United States.

In the late 1930s, Nadia Boulanger recorded little-known works of Claudio Monteverdi, championed rarely performed works by Heinrich Schütz and Fauré, and promoted early French music. She spent the period of World War II in the United States, mainly as a teacher at Washington (D.C.) College of Music and the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Md. Returning to France, she taught again at the Paris and American conservatories, becoming director of the latter in 1949.

In 1936, Boulanger substituted for Alfred Cortot in some of his piano masterclasses, coaching the students in Mozart’s keyboard works. Later in the year, she traveled to London to broadcast her lecture-recitals for the BBC, as well as to conduct works including Schütz, Fauré, and Lennox Berkeley. Noted as the first woman to conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra, she received acclaim for her performances. She recorded and released six discs of madrigals for HMV in 1937. This helped reach her music to a more widespread audience and she received very good reviews from critics though some objected to the use of modern instruments.

Contact with Stravinsky and his circle increased her determination to bring contemporary music to a wider audience and, as conductor and pianist, Nadia Boulanger premiered many works by rising composers, including the first performance in Washington in 1938 of Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks and, at the keyboard, the first performance of an organ symphony written for her by Aaron Copland. Boulanger spent the Second World War in the United States, where she was the first to record Monteverdi, and the first woman to direct the Boston Symphony and New York Philharmonic orchestras.

Nadia moved to New York in 1940 where she taught harmony, fugue, and advanced composition at the Longy School of Music. A couple of years later she began teaching at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Her teaching at the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau was highly disciplined but inspirational. She readily embraced serial and other unconventional techniques, but her principal models were Fauré, Bartók, Debussy, Ravel, and of course, Stravinsky. Her pupils came from all over the world, among them the American composers Walter Piston, Roy Harris, Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, and Philip Glass. Her British pupils included Lennox Berkeley, Thea Musgrave, and Nicholas Maw. Her French alumni were Jean Françaix and Igor Markevich, a Russian-born protégé of Diaghilev.

Leaving America at the end of 1945, Nadia Boulanger returned to France in January 1946. There she accepted a position of professor of accompaniment au piano at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1953, she was appointed an overall director of the Fontainebleau School. She also continued her touring to other countries. As a long-standing friend of the family (and officially as chapel-master to the Prince of Monaco), Boulanger was asked to organize the music for the wedding of Prince Rainier of Monaco and the American actress, Grace Kelly, in 1956. In 1958, she returned to the US for a six-week tour. She combined broadcasting, lecturing, and making four television films. Also in 1958, she was inducted as an Honorary Member into Sigma Alpha Iota, the international women’s music fraternity, by the Gamma Delta chapter at the Crane School of Music in Potsdam, New York.

Over the 1950s Nadia Boulanger continued conducting and teaching, and also make four television films. She organized the music for the wedding of Prince Rainier of Monaco and the American actress Grace Kelly. During her later years, her eyesight and hearing began to fail though she remained active until the end of her life.

In 1962, she toured Turkey, where she conducted concerts with her young protégée Idil Biret. Later that year, she was invited to the White House of the United States by President John F. Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline, and in 1966, she was invited to Moscow to the jury for the International Tchaikovsky Competition, chaired by Emil Gilels. While in England, she taught at the Yehudi Menuhin School. She also gave lectures at the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, all of which were broadcast by the BBC. Boulanger worked almost until her death in 1979 in Paris.

Awards and Honor

Nadia Boulanger was presented with the Henry Howland Memorial Prize in 1962 in recognition of her achievement of marked distinction in the field of fine arts.

Death and Legacy

Nadia Boulanger died on October 22, 1979, in Paris, France at the ripe old age of 92. She is buried at the Montmartre Cemetery, as is her sister Lili.

Nadia Boulanger was a highly influential teacher of music and also a very talented composer who became the first woman to conduct many major orchestras including the BBC Symphony, Boston Symphony, and New York Philharmonic orchestras.

Nadia Boulanger claimed to enjoy all “good music”. According to Lennox Berkeley, “A good waltz has just as much value to her as a good fugue, and this is because she judges a work solely on its aesthetic content.” However, her taste has also been described as, “to put it mildly, eclectic”: “She was an admirer of Debussy and a disciple of Ravel. Although she bore little sympathy for Schoenberg and the Viennese dodecaphonicians, she was an ardent champion of Stravinsky”. She insisted on complete attention at all times: “Anyone who acts without paying attention to what he is doing is wasting his life. I’d go so far as to say that life is denied by lack of attention, whether it be to cleaning windows or trying to write a masterpiece.”

Information Source: