Biography of Miriam Makeba

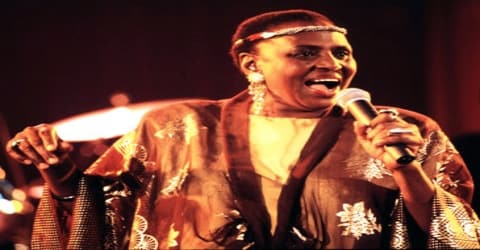

Miriam Makeba – South African singer, songwriter, actress, United Nations goodwill ambassador, and civil-rights activist.

Name: Zenzile Miriam Makeba

Date of Birth: 4 March 1932

Place of Birth: Prospect Township, Johannesburg, Union of South Africa

Date of Death: 9 November 2008 (aged 76)

Place of Death: Castel Volturno, Italy

Occupation: Singer, Songwriter, Actress

Father: Caswell Makeba

Mother: Christina Makeba

Spouse/Ex: Sonny Pilay (m. 1959-1959), Hugh Masekela (m. 1964-1966), Stokely Carmichael (m. 1968-1978)

Early Life

South African-born singer who became known as Mama Africa, one of the world’s most prominent black African performers in the 20th century, Miriam Makeba was born on 4 March 1932 in the black township of Prospect, near Johannesburg, South Africa. Associated with musical genres including Afropop, jazz, and world music, she was an advocate against apartheid and white-minority government in South Africa.

Makeba’s career flourished in the United States, and she released several albums and songs, her most popular being “Pata Pata” (1967). Along with Belafonte, she received a Grammy Award for her 1965 album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba. She testified against the South African government at the United Nations and became involved in the civil rights movement.

Also known by her nickname Mama Africa, she is the person who took African traditional music sounds to the world stage and performed in many countries around the globe, achieving magnum success while. She was strongly against white supremacy which was very much apparent in South Africa during 60s and 70s and spoke in favor of the anti-apartheid movements all through her life until things got a lot better in the 90s. Finding her musical voice while going through a very rough childhood wasn’t easy but Miriam showed traits of a true artist. She grew out of her disabilities and her ‘no excuses’ attitude placed her among the best musicians to come out of Africa. She bagged a Grammy award for her album ‘An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba’ and is regularly credited with making afro-pop a thing to look out for in America, which basically is a music form that combines African Zulu with modern music sounds. She began to write and perform music more explicitly critical of apartheid; the 1977 song “Soweto Blues”, written by her former husband Hugh Masekela, was about the Soweto uprising. After apartheid was dismantled in 1990, Makeba returned to South Africa. She continued recording and performing, including a 1991 album with Nina Simone and Dizzy Gillespie, and appeared in the 1992 film Sarafina!. She was named a UN goodwill ambassador in 1999 and campaigned for humanitarian causes. She died of a heart attack during a 2008 concert in Italy.

Makeba was among the first African musicians to receive worldwide recognition. She brought African music to a Western audience and popularized the world music and Afropop genres. She also made popular several songs critical of apartheid, and became a symbol of opposition to the system, particularly after her right to return was revoked. Upon her death, former South African President Nelson Mandela said that “her music inspired a powerful sense of hope in all of us.”

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Miriam Makeba, in full Zenzile Miriam Makeba, nicknamed Mama Africa, was born on 4th March 1932, in a poor black household in Johannesburg, South Africa, to a domestic worker mother and a Xhosa teacher father, who died when Miriam was just six-years-old. Miriam had a very tough life ever since she was conceived as just a few days after her birth, her mother got arrested for the possession of a beer which was illegal to sell and produce in South Africa. As a result, Miriam had to spend the first six months of her life in Jail with her mother.

As a child, Makeba sang in the choir of the Kilnerton Training Institute in Pretoria, an all-black Methodist primary school that she attended for eight years. Her talent for singing earned her praise at school. Makeba was baptized a Protestant, and sang in church choirs, in English, Xhosa, Sotho, and Zulu; she later said that she learned to sing in English before she could speak the language. When her father died, Makeba, despite being a small child, had to work to survive. Their family with six children depended on her mother and Makeba for their needs. Makeba, as a teenager, got married to a policeman, who was a narcissist and used to beat her up.

At the age of 18, Miriam Makeba was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. Her mother, who also happened to be a traditional healer, cured her. Sometime later, Miriam found a new way to grow around her troubles and started working on her music.

Personal Life

In 1949, Miriam Makeba married James Kubay, a policeman in training, with whom she had her only child, Bongi Makeba, in 1950. Makeba was then diagnosed with breast cancer, and her husband, who was said to have beaten her, left her shortly afterward, after a two-year marriage.

Her second marriage took place in 1964, with musician Hugh Masekela, which also lasted two whole years. Makeba got married for a third time to Stokely Carmichael. He was a Trinidadian-American civil rights activist. The couple first moved to Guinea then Belgium, but they divorced after 9 years.

Career and Works

Miriam Makeba started her professional musical career making American song covers with the South African band ‘The Cuban Brothers’, but she got bored of it and at the age of 21, she found her calling in Jazz music. She partnered up with the group ‘The Manhattan Brothers’ and the all-women group named ‘The Skylarks’, which combined traditional African vocals with westernized jazz sounds. It clicked with music lovers on a deeper level and these two bands started getting mentioned as the trendsetters in local and to some extent, in western media.

In 1956, Gallotone Records released “Lovely Lies”, Makeba’s first solo success; the Xhosa lyric about a man looking for his beloved in jails and hospitals was replaced with the unrelated and innocuous line “You tell such lovely lies with your two lovely eyes” in the English version. The record became the first South African record to chart on the United States Billboard Top 100. In 1957, Makeba was featured on the cover of Drum magazine. During this time, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was starting to boil up and Miriam came out in full supported. She secretly appeared in a documentary film ‘Come Back, Africa’, the film which later won the top honor at the Venice film festival.

Although she left to form an all-female group named the Skylarks in 1958, she reunited with members of the Manhattan Brothers when she accepted the lead female role in a musical version of King Kong, which told the tragic tale of Black African boxer, Ezekiel “King Kong” Dlamani, in 1959. The same year, she began an 18-month tour of South Africa with Alf Herbert’s musical extravaganza, African Jazz and Variety, and made an appearance in a documentary film, Come Back, Africa. These successes led to invitations to perform in Europe and the United States.

The film’s international success opened Miriam’s way for international acclaim and she got signed on to perform in the US and Europe. She landed in London in the late ’50s and met Henry Belafonte, whom she regarded as her mentor. She released the song ‘Pata Pata’ which is still known among her most popular songs and put her in the class of best international musicians. She kept switching between London and New York during that time and got married briefly to an Indian man, but upon divorce, she moved to New York City to concentrate on making music.

Makeba then moved to New York, making her US music debut on 1 November 1959 on The Steve Allen Show in Los Angeles for a television audience of 60 million. Her New York debut at the Village Vanguard occurred soon after; she sang in Xhosa and Zulu and performed a Yiddish folk song. Her audience at this concert included Miles Davis and Duke Ellington; her performance received strongly positive reviews from critics. She first came to popular and critical attention in jazz clubs, after which her reputation grew rapidly. Belafonte, who had helped Makeba with her move to the US, handled the logistics for her first performances. When she first moved to the US, Makeba lived in Greenwich Village, along with other musicians and actors. As was common in her profession, she experienced some financial insecurity and worked as a babysitter for a period.

In 1960 Makeba was denied reentry into South Africa, and she lived in exile for three decades thereafter. She continued making music and wooing Americans with her musical skills and was being hailed as ‘the most exciting young musician’. Her songs ‘The Click Song’ and ‘Malaika’ became popular across the US for introducing Americans to the African sounds, which was a refreshing change. In 1963 the South African government banned her records and revoked her passport.

In 1964, Makeba released her second studio album for RCA, The World of Miriam Makeba. An early example of world music, the album peaked at number eighty-six on the Billboard 200. Makeba’s music had a cross-racial appeal in the US; white Americans were attracted to her image as an “exotic” African performer, and black Americans related their own experiences of racial segregation to Makeba’s struggle against apartheid.

Miriam’s popularity reached the then American president, John F. Kennedy, who claimed that he was a huge fan of the singer and invited her over to perform at his son’s birthday party in 1962. Three years later, she along with her mentor Belafonte, released a duo album titled ‘An Evening with Belafonte and Makeba’, which went on to receive the Grammy award for best folk album of the year in 1966. The duos ‘Train Song’ and ‘Cannon’ also received widespread love from around the country.

Makeba was embraced by the African American community. “Pata Pata,” Makeba’s signature tune, was written by Dorothy Masuka and recorded in South Africa in 1956 before eventually becoming a major hit in the U.S. in 1967. Her career took another major turn in the mid-80s, when she came in touch with Paul Simon, a cult figure in the American music scene. She embarked on a glorious ‘Graceland’ tour, which turned her life around and the European countries got officially introduced to the brilliant musician that Miriam was. The tour also gave her the opportunity to be vocal about the apartheid movement back in South Africa and raise awareness about the cause.

In 1975, Makeba recorded an album, A Promise, with Joe Sample, Stix Hooper, Arthur Adams, and David T. Walker of the Crusaders. Makeba joined Paul Simon and South Africa ‘s Ladysmith Black Mambazo during their worldwide Graceland tour in 1987 and 1988. Two years later, she joined Odetta and Nina Simone for the One Nation tour.

Her autobiography, Makeba: My Story (co-authored with James Hall), appeared in 1988. In 1990 the South African black activist Nelson Mandela, who had just been released from his extended imprisonment, encouraged Makeba to return to South Africa, and she performed there in 1991 for the first time since her exile.

In 2005 Miriam Makeba announced that she would retire and began a farewell tour, but despite having osteoarthritis, continued to perform until her death. During this period, her grandchildren Nelson Lumumba Lee and Zenzi Lee, and her great-grandchild Lindelani, occasionally joined her performances. Although she was plagued by health problems, she continued to perform in subsequent years, and she died of a heart attack shortly after giving a concert in Italy in 2008.

Awards and Honor

On 16 October 1999, Miriam Makeba was named a Goodwill Ambassador of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Makeba shared the 2001 Polar Music Prize with Sofia Gubaidulina. They received their prize from Carl XVI Gustaf, the King of Sweden, during a nationally televised ceremony at Berwaldhallen, Stockholm, on 27 May 2002.

In 2004, Makeba was voted 38th in a poll ranking 100 Great South Africans. She also received several honorary doctorates.

In 2014 Makeba was honored (along with Nelson Mandela, Albertina Sisulu, and Steve Biko) in the Belgian city of Ghent, which named a square after her, the “Miriam Makebaplein”.

Death and Legacy

On 9 November 2008, Miriam Makeba fell ill during a concert in Castel Volturno, near Caserta, Italy. The concert had been organized to support the writer Roberto Saviano in his stand against the Camorra, a criminal organization active in the Campania region. She suffered a heart attack after singing her hit song “Pata Pata”, and was taken to the Pineta Grande clinic, where doctors were unable to revive her.

Among the songs for which Makeba was internationally known were “Pata Pata” and one known as the “Click Song” in English (“Qongqothwane” in Xhosa); both featured the distinctive click sounds of her native Xhosa language. Makeba made 30 original albums, in addition to 19 compilation albums and appearances on the recordings of several other musicians.

In January 2000, her album, Homeland, produced by the New York City-based record label Putumayo World Music, was nominated for a Grammy Award in the Best World Music Album category. Makeba worked closely with Graça Machel-Mandela, the South African first lady, advocating for children suffering from HIV/AIDS, child soldiers, and the physically handicapped. She established the Makeba Centre for Girls, a home for orphans, described in an obituary as her most personal project. She also took part in the 2002 documentary Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony, which examined the struggles of black South Africans against apartheid through the music of the period. Makeba’s second autobiography, Makeba: The Miriam Makeba Story, was published in 2004.

Makeba has also been associated with the movement against colonialism, with the civil rights and black power movements in the US, and with the Pan-African movement. She called for unity between black people of African descent across the world: “Africans who live everywhere should fight everywhere. The struggle is no different in South Africa, the streets of Chicago, Trinidad or Canada. The Black people are the victims of capitalism, racism and oppression, period”. After marrying Carmichael she often appeared with him during his speeches; Carmichael later described her presence at these events as an asset, and Feldstein wrote that Makeba enhanced Carmichael’s message that “black is beautiful”. Along with performers such as Simone, Lena Horne, and Abbey Lincoln, she used her position as a prominent musician to advocate for civil rights. Their activism has been described as simultaneously calling attention to racial and gender disparities, and highlighting “that the liberation they desired could not separate race from sex”. Makeba’s critique of second-wave feminism as being the product of luxury led to observers being unwilling to call her a feminist. Scholar Ruth Feldstein stated that Makeba and others influenced both black feminism and second-wave feminism through their advocacy, and the historian Jacqueline Castledine referred to her as one of the “most steadfast voices for social justice”.

Information Source: