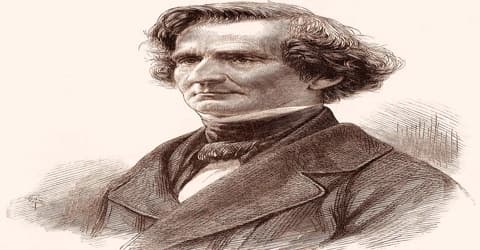

Biography of Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz – French Romantic Composer.

Name: Louis-Hector Berlioz

Date of Birth: December 11, 1803

Place of Birth: La Côte-Saint-André, France

Date of Death: March 8, 1869

Place of Death: rue de Calais, Paris, France

Occupation: Composer

Father: Louis-Joseph Berlioz

Mother: Marie-Antoinette

Spouse/Ex: Marie Recio (m. 1854–1862), Harriet Smithson (m. 1833–1842)

Children: Louis Berlioz

Early Life

Hector Berlioz, French composer, critic, and conductor of the Romantic period, was born on 11 December 1803, the eldest child of Louis Berlioz (1776–1848), a physician, and his wife, Marie-Antoinette Joséphine, née Marmion (1784–1838). He was known largely for his Symphonie fantastique (1830), the choral symphony Roméo et Juliette (1839), and the dramatic piece La Damnation de Faust (1846). His last years were marked by fame abroad and hostility at home.

The elder son of a provincial doctor, Berlioz was expected to follow his father into medicine, and he attended a Parisian medical college before defying his family by taking up music as a profession. His independence of mind and refusal to follow traditional rules and formulas put him at odds with the conservative musical establishment of Paris. He briefly moderated his style sufficiently to win France’s premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, in 1830 but he learned little from the academics of the Paris Conservatoire. Opinion was divided for many years between those who thought him an original genius and those who viewed his music as lacking in form and coherence.

Composer, critic, and conductor, this Romantic musician contributed greatly to the burgeoning romanticism. Not only that, he also enormously influenced the orchestral techniques of the era. In fact, his contribution to Romantic music is so huge that he is often put in the same pedestal as that of writer Victor Hugo and painter Eugene Delacroix. Hector Berlioz made ground-breaking innovations in music, breaking away from the customary trends and introduced passion and emotion in the music. His findings in the realms of music have been so innovative that he is considered as the most original composers of his times.

Berlioz completed three operas, the first of which, Benvenuto Cellini, was an outright failure. The second, the huge epic Les Troyens (The Trojans), was so large in scale that it was never staged in its entirety during his lifetime. His last opera, Béatrice et Bénédict – based on Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado About Nothing – was a success at its premiere but did not enter the regular operatic repertoire. Meeting only occasional success in France as a composer, Berlioz increasingly turned to conduct, in which he gained an international reputation.

Most famous for his “Symphonie Fantastique”, this musician has a string of feats to his name. For some of his works, he employed huge orchestral forces and several of his concerts were conducted with more than a thousand musicians. For a composer who was loved abroad and criticized at home, life was nothing less than a roller coaster ride. But despite everything, his genius stands tall when it comes to music.

Berlioz was highly regarded in Germany, Britain, and Russia both as a composer and as a conductor. To supplement his earnings he wrote musical journalism throughout much of his career; some of it has been preserved in book form, including his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844), which was influential in the 19th and 20th centuries. Berlioz died in Paris at the age of 65.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Hector Berlioz, in full Louis-Hector Berlioz, was born on 11 December 1803 at La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère. His father, Louis Berlioz, a physician, is believed to have introduced acupunctural techniques in Europe. His mother, Marie-Antoinette, was a devout Roman Catholic. His birthplace was the family home in the commune of La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère, in south-eastern France. His parents had five more children, three of whom died in infancy; their surviving daughters, Nanci and Adèle, remained close to Berlioz throughout their lives.

Hector Berlioz, as he was known, was entranced with music as a child. He learned to play the flute and guitar and became a self-taught composer. He started his education at the local seminary. Unfortunately, due to the on-going war with Great Britain and other European powers, it closed down in 1811. Thereafter, he continued his education under his father.

At the age of 10, Berlioz was briefly placed at a local school to study Latin. However, his father soon took him out and began to supervise his entire education himself. However, he could not inspire in little Hector any love for classical languages. The boy detested learning the verses by heart. Instead, he spent hours studying the atlas, spellbound at the complex patterns created by islands, straits, and capes. He soon started wondering what kind of vegetation, climate or people those distant lands would have.

Berlioz recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin; the classics nonetheless made an impression on him, and he was moved to tears by Virgil’s account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas. Later he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and – because his father planned a medical career for his – anatomy.

Heeding his physician father’s wishes, Berlioz went to Paris in 1821 to study medicine. However, much of his time was spent at the Paris-Opéra, where he absorbed Christoph Willibald Gluck’s operas. Two years later, he left medicine behind to become a composer.

In 1824 Berlioz graduated from medical school, after which he abandoned medicine, to the strong disapproval of his parents. His father suggested law as an alternative profession and refused to countenance music as a career. He reduced and sometimes withheld his son’s allowance, and Berlioz went through some years of financial hardship.

Personal Life

Hector Berlioz fell in love for the first time with Estelle Fornier, six years his senior, at the age of twelve. However, unlike other early crushes, he carried the flame until the end of his life.

On 11 September 1827, while attending a production by a traveling English theatre company, Berlioz saw Harriet Smithson, an Irish-born actress, playing Ophelia. He was immediately infatuated with her and began to flood her with love letters. Harriet did not respond.

(Marie (“Camille”) Moke)

Berlioz fell in love with a nineteen-year-old pianist, Marie (“Camille”) Moke in 1830. His feelings were reciprocated, and the couple planned to be married.

(Harriet Smithson as Ophelia)

On his return, Berlioz met Harriet Smithson in person. Although he did not know enough English and she did not know French, the two got married on 3 October 1833. Their only child, Louis Berlioz was born on 14 August 1834. Soon Berlioz realized that it was easier to admire Harriet from afar than to live with her. She was jealous of his success and the two had frequent outbursts. Subsequently, she moved out of their matrimonial house. However, Berlioz financially supported her till her death.

Meanwhile, Berlioz had developed a relationship with Marie Recio, a singer, and married her on 19 October 1854. In June 1862 Berlioz’s wife died suddenly, aged 48. She was survived by her mother, to whom Berlioz was devoted, and who looked after him for the rest of his life.

After the death of his second wife, Berlioz had two romantic interludes. During 1862 he met – probably in the Montmartre Cemetery – a young woman less than half his age, whose first name was Amélie and whose second, possibly married, the name is not recorded. Almost nothing is known of their relationship, which lasted for less than a year. After they ceased to meet, Amélie died, aged only 26. Berlioz was unaware of it until he came across her grave six months later. Cairns hypothesizes that the shock of her death prompted him to seek out his first love, Estelle, now a widow aged 67. He called on her in September 1864; she received him kindly, and he visited her in three successive summers; he wrote to her nearly every month for the rest of his life.

His only son, Louis, who later grew up to be the Commander at the merchant navy, also died on 5 June 1867 from yellow fever. The deaths left him devastated.

Career and Works

Accordingly, from 1822, Hector Berlioz informally started studying music under Jean-François Le Sueur, the director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire. Here he learned to experiment in program music.

In August 1823 Berlioz made the first of many contributions to the musical press: a letter to the journal Le Corsaire defending French opera against the incursions of its Italian rival. He contended that all of Rossini’s operas put together could not stand comparison with even a few bars of those of Gluck, Spontini or Le Sueur. By now he had composed several works including Estelle et Némorin and Le Passage de la mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea) – both since lost.

On 12 January 1824, Berlioz was made a Bachelier ès sciences physiques. Despite receiving his degree, he continued to concentrate on music, completely abandoning medicine later in the same year. Also in 1824, he wrote, ‘Messe solennelle’, a setting of the Catholic Solemn Mass.

In 1824 Berlioz composed a Messe solennelle. It was performed twice, after which he suppressed the score, which was thought lost until a copy was discovered in 1991. During 1825 and 1826 he wrote his first opera, Les francs-juges, which was not performed and survives only in fragments, the best known of which is the overture. In later works, he reused parts of the score, such as the “March of the Guards”, which he incorporated four years later in the Symphonie fantastique as the “March to the Scaffold”.

In 1826, Berlioz enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire. The next year, he saw Harriet Smithson in the role of Ophelia and became captivated by the Irish actress. His ardor inspired the Symphonie fantastique (1830), a piece that broke new ground in orchestral expression. With its use of music to relate a story of desperate passion, it was a hallmark of Romantic composition.

In August 1826 Berlioz was admitted as a student to the Conservatoire, studying composition under Le Sueur and counterpoint and fugue with Anton Reicha. In the same year, he made the first of four attempts to win France’s premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, and was eliminated in the first round. The following year, to earn some money, he joined the chorus at the Théâtre des Nouveautés. He competed again for the Prix de Rome, submitting the first of his Prix cantatas, La mort d’Orphée, in July. Later that year he attended productions of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet at the Théâtre de l’Odéon given by Charles Kemble’s touring company.

In 1827, Berlioz conducted the second performance of ‘Messe solennelle’ at Saint-Eustache on 22 November 1827. It was his first experience as a conductor. Encouraged, he presented his first orchestral concert on 26 May 1828 at the Conservatory.

Berlioz’s fascination with Shakespeare’s plays prompted him to start learning English during 1828 so that he could read them in the original. At around the same time he encountered two further creative inspirations: Beethoven and Goethe. He heard Beethoven’s third, fifth and seventh symphonies performed at the Conservatoire, and read Goethe’s Faust in Gérard de Nerval’s translation. Beethoven became both an ideal and an obstacle for Berlioz – an inspiring predecessor but a daunting one. Goethe’s work was the basis of Huit scènes de Faust (Berlioz’s Opus 1), premiered the following year and reworked and expanded much later as La damnation de Faust.

Also in 1828, he submitted his cantata ‘Herminie’ at Prix de Rome and won the second prize. He had earlier submitted two more pieces; a fugue in 1826 and a cantata entitled ‘La Mort d’Orphée’ in 1827, but they failed to win any prize.

Berlioz was largely apolitical, and neither supported nor opposed the July Revolution of 1830, but when it broke out he found himself in the middle of it. He recorded events in his Mémoires:

I was finishing my cantata when the revolution broke out … I dashed off the final pages of my orchestral score to the sound of stray bullets coming over the roofs and pattering on the wall outside my window. On the 29th I had finished and was free to go out and roam about Paris till morning, pistol in hand.

Since the first prize came with a five-year pension, which he badly needed, he kept on trying. Finally, he won the prize in 1830 with his fourth cantata, entitled ‘Sardanapale’. This was also the year when he wrote and composed ‘Symphonie fantastique.’ By that time, he had established himself in the music world of Paris with his concerts at the Conservatory and this work further enhanced his fame. He composed his great Requiem, the Grande Messe des morts (1837), the symphonies Harold en Italie (1834) and Roméo et Juliette (1839), and the opera Benvenuto Cellini (Paris, 1838).

On 9 December 1832 Berlioz presented a concert of his works at the Conservatoire. The programme included the overture of Les francs-juges, the Symphonie fantastique – extensively revised since its premiere – and Le Retour à la vie, in which Bocage, a popular actor, declaimed the monologues. Through a third party, Berlioz had sent an invitation to Harriet Smithson, who accepted, and was dazzled by the celebrities in the audience. Among the musicians present were Liszt, Frédéric Chopin, and Niccolò Paganini; writers included Alexandre Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo, and George Sand. The concert was such a success that the programme was repeated within the month, but the more immediate consequence was that Berlioz and Smithson finally met.

In the 1840s, touring throughout Europe began to offer Berlioz another source of income; he was particularly appreciated as a conductor in Germany, Russia, and England. When the production of another choral work, La Damnation de Faust, became a financial sinkhole after its premiere in 1846, touring again came to the rescue.

He wrote for L’Europe littéraire (1833), Le rénovateur (1833–1835), and from 1834 for the Gazette musicale and the Journal des débats. He was the first, but not the last, prominent French composer to double as a reviewer: among his successors were Fauré, Messager, Dukas, and Debussy. His journalism consisted mainly of music criticism, some of which he collected and published, such as Evenings in the Orchestra (1854), but also more technical articles, such as those that formed the basis of his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844).

In November 1847, after a four-month visit to Russia, he embarked on a seven-month tour of England, where he was appointed conductor of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. It was also the time when he started writing his ‘Mémoires.’

Berlioz wrote in his Mémoires (1870) how unproductive he was after the rich output of the Paris years, which had brought forth an oratorio, numerous cantatas, two dozen songs, a mass, part of an opera, two overtures, a fantasia on Shakespeare’s Tempest, and eight scenes from Goethe’s Faust, as well as the Symphonie fantastique. Even in Italy, however, Berlioz filled notebooks, met the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, made a lifelong friend of Mendelssohn, and tramped the hills with his guitar over his shoulder, playing for the peasants and banditti whose meals he shared. The impressions gathered in Italy remained a source of both musical and dramatic inspiration down to the last of his works, Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict (first performed 1862).

Berlioz found his financial footing in the 1850s, when his L’Enfance du Christ (1854) was a success and he was elected to the Institut de France, thus enabling him to receive a stipend. He wrote Les Troyens, inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid, at this time, but only got to see a few of the opera’s acts be performed in 1863. He also returned to William Shakespeare once more, creating the opera Béatrice et Bénédict (based on Much Ado About Nothing), which had a successful debut in Germany in 1862.

Among Berlioz’s dramatic works, two became internationally known: La Damnation de Faust (1846) and L’Enfance du Christ (1854). Two others began to emerge from neglect after World War I: the massive two-part drama Les Troyens (1855–58), based on Virgil’s story of Dido and Aeneas, and the short, witty comedy Béatrice et Bénédict, written between 1860 and 1862 and based on Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. For all these Berlioz wrote his own librettos. He also wrote a Te Deum (1849; perfomed 1855), which is a fitting counterpart to the Requiem, and between 1843 and 1856 he orchestrated his songs, including the song cycle Les Nuits d’été (Summer Nights). Among his best-known overtures are Le Roi Lear (1831), Le Carnaval Romain (1844), based on material from Benvenuto Cellini, and Le Corsaire (1831–52).

In 1863 Berlioz published his last signed article for the ‘Journal des débats’ and by 1865, he had 1200 copies of his ‘Mémoires’ printed; they were mostly kept away to be published after his death. Meanwhile, in 1864 Berlioz was made Officier de la Légion d’honneur. At the same time, he continued with his musical tour, visiting Vienna in 1866 and conducting the first complete performance of ‘La Damnation de Faust’ there on 16th December.

The outstanding characteristics of Berlioz’s music it’s dramatic expressiveness and variety account for the feeling of attraction or repulsion that it produces in the listener. Its variety also means that devotees of one work may dislike others, as one finds lovers of Shakespeare who detest Othello. But Berlioz also presents a particular difficulty of musicianship in being closer to the true sources of music than to its German, Italian, or French conventions; his melody is abundant and extended and is often disconcerting to the lover of four-bar phrases; his harmony may be obvious or subtle, but it is always functional and frequently depends on elements of timbre; his modulations can be harsh and may even seem harsher than they would in another composer, because he uses his effects sparingly and achieves much by small means and adroit contrasts. He is also equally remembered for his book, ‘Grand traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes.’ Abbreviated in English as ‘Treatise on Instrumentation’, it is a technical study on Western musical instruments and contributes significantly to the modern orchestra.

In February 1867, he visited Cologne and in November he went to Russia, from where he returned on 17 February 1868. His last trip was made to Grenoble; he went there in August to preside over a choral competition.

Death and Legacy

(Grave of Hector Berlioz)

Towards the end of his life, Berlioz was inflicted with intestinal diseases, which often caused acute pain. After arriving back in Paris Hector Berlioz gradually grew weaker and died at his house in the Rue de Calais on 8 March 1869, at the age of 65. His funeral was held at Église de la Trinité on 11 March and he was buried in Montmartre Cemetery with his two wives, who were exhumed and re-buried next to him.

Sometime in the 1850s, Berlioz wrote ‘Shepherd’s Farewell’ under the pen name of Pierre Ducré and had it performed in two concerts. His critics praised it highly, some of them going to the extent of declaring that Berlioz should learn from it while others said, he would never be able to write something like it.

Hector Berlioz left behind many innovative compositions that had set the tone for the Romantic period; though the originality of his work may have worked against him during his lifetime, appreciation of his music would continue to grow after his death.

Berlioz is best remembered for his composition ‘Grande Messe des morts.’ It derives its text from the traditional Latin Requiem Mass and has the duration of about ninety minutes. It consists of ten movements. It and showcases a grand orchestration of woodwind and brass instruments. He is also known for his earlier composition ‘Symphonie fantastique.’ Considered an important piece of the early Romantic period, this program symphony is famous for its dream-like nature.

By far the most recorded of Berlioz’s works is the Symphonie fantastique. The discography of the British Hector Berlioz website lists 96 recordings, from the pioneering version by Gabriel Pierné and the Concerts Colonne in 1928 to those conducted by Beecham, Pierre Monteux, Charles Munch, Herbert von Karajan and Otto Klemperer to more recent versions including those of Boulez, Marc Minkowski, Yannick Nézet-Séguin and François-Xavier Roth.

In the creation of drama and atmosphere, Berlioz excels in scenes of melancholy, introspection, love gentle or passionate the contemplation of nature, and the tumult of crowds. His intention throughout is to combine truth with musical sensations, be they powerful or (to quote Shaw again) “wonderful in their tenuity and delicacy, unearthly, unexpected, unaccountable.”

Information Source: