Biography of Dylan Thomas

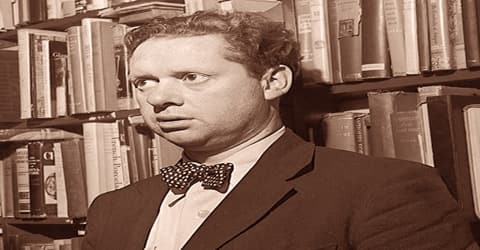

Dylan Thomas – Welsh poet and writer.

Name: Dylan Marlais Thomas

Date of Birth: 27 October 1914

Place of Birth: Uplands, Swansea, Glamorgan, Wales

Date of Death: 9 November 1953 (aged 39)

Place of Death: New York City, United States

Father: David John Thomas

Mother: Florence Hannah

Occupation: Poet and writer

Spouse: Caitlin Macnamara (m. 1937–1953, his death)

Children: Aeronwy Thomas, Llewelyn Edouard Thomas, Colm Garan Hart Thomas

Early Life

Dylan Thomas (a Welsh poet and writer) was born October 27, 1914, Swansea, Glamorgan (now in Swansea), Wales. An undistinguished pupil, he left school at 16 and became a journalist for a short time. Many of his works appeared in print while he was still a teenager; however, it was the publication in 1934 of “Light breaks where no sun shines” that caught the attention of the literary world.

Although he wrote entirely in English, his works were mostly rooted in the geographical area of his homeland, Wales. He was never a good student though he was extremely intelligent. From his schoolteacher father, he derived his intellectual as well as literary flair while his temperament was inherited from his mother, who also inducted in him immense respect for his Celtic heritage.

His works include the poems “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “And death shall have no dominion”; the ‘play for voices’ Under Milk Wood, and stories and radio broadcasts such as A Child’s Christmas in Wales and Portrait o0f the Artist as a Young Dog. He became widely popular in his lifetime and remained so after his premature death at the age of 39 in New York City. By then he had acquired a reputation, which he had encouraged, as a “roistering, drunken and doomed poet”.

His first book of poems was published when he was still in his teens and by the time he was twenty, he had become an acclaimed poet. Later he started writing prose as well, which also earned him great praise. Unfortunately, he also developed a drinking problem while he was in his early twenties and as a result, he had to endure financial problems all through his life. It also ruined his health and he died at the age of thirty-nine from pneumonia brought on by excess drinking.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Dylan Thomas, in full Dylan Marlais Thomas, was born on 27 October 1914 in Swansea, South Wales. His father, David John Thomas, was an English teacher at Swansea Grammar School for Boys while his mother, Florence Hannah (née Williams), was a seamstress. He had one sister named Nancy Marles, eight years senior to him.

The children spoke only English, though their parents were bilingual in English and Welsh, and David Thomas gave Welsh lessons at home. Thomas’s father chose the name Dylan, which could be translated as “son of the sea”, after Dylan ail Don, a character in The Mabinogion. His middle name, Marlais, was given in honor of his great-uncle, William Thomas, a Unitarian minister and poet whose bardic name was Gwilym Marles. Dylan, pronounced ‘dəlan’ (Dull-an) in Welsh, caused his mother to worry that he might be teased as the “dull one”. When he broadcast on Welsh BBC, early in his career, he was introduced using this pronunciation. Thomas favored the Anglicised pronunciation and gave instructions that it should be Dillan /ˈdɪlən/.

He attended the Swansea Grammar School, where he received all of his formal education. As a student, he made contributions to the school magazine and was keenly interested in local folklore (stories passed down within a culture). He said that as a boy he was “small, thin, indecisively active, quick to get dirty, curly.” During these early school years, Thomas befriended Daniel Jones, another local schoolboy. The two would write hundreds of poems together, and as adults Jones would edit a collection of Thomas’s poetry.

In 1928, Thomas won the school’s mile race and his photograph was published in some local newspaper. For some reason, he considered it to be a very major achievement for he carried the photograph with him until his death. Sometimes now, he also started writing poetries in a penny notebook, many of which were published in the school magazine. The first poem, dated 27 April 1930, was titled ‘Osiris, come to Isis.’

Later he also became an editor of the magazine. However, he did not complete his education and left the school in 1931. He was then sixteen years old. After leaving school, Thomas supported himself as an actor, reporter, reviewer, scriptwriter, and with various odd jobs.

Personal Life

In early 1936, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara (1913–94), a 22-year-old blonde-haired, blue-eyed dancer of Irish descent. She had run away from home, intent on making a career in dance, and aged 18 joined the chorus line at the London Palladium. Introduced by Augustus John, Caitlin’s lover, they met in The Wheatsheaf pub on Rathbone Place in London’s West End. Laying his head in her lap, a drunken Thomas proposed. Thomas liked to comment that he and Caitlin were in bed together ten minutes after they first met. Although Caitlin initially continued her relationship with John, she and Thomas began a correspondence, and in the second half of 1936 were courting.

On 11 July 1937, Dylan Thomas married Caitlin Macnamara. Although they remained married until his death, they had a very tremulous relationship, each having multiple affairs outside marriage. In spite of that, the couple had three children, Llewelyn, Aeronwy, and Colm. Among them, their second child, Aeronwy Bryn Thomas-Ellis, grew up to be a translator of Italian poems.

In early 1943, Thomas began a relationship with Pamela Glendower; one of several affairs he had during his marriage. The affairs either ran out of steam or were halted after Caitlin discovered his infidelity.

Thomas claimed that his poetry was “the record of my individual struggle from darkness toward some measure of light.… To be stripped of darkness is to be clean, to a strip of darkness is to make clean.” He also wrote that his poems “with all their crudities, doubts, and confusions, are written for the love of man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damned fool if they weren’t.” Passionate and intense, vivid and violent, Thomas wrote that he became a poet because “I had fallen in love with words.” His sense of the richness and variety and flexibility of the English language shines through all of his work.

His widow, Caitlin, died in 1994 and was buried alongside him. Thomas’s father “DJ” died on 16 December 1952 and his mother Florence in August 1958. Thomas’s elder son, Llewelyn, died in 2000, his daughter, Aeronwy in 2009 and his youngest son Colm in 2012.

Career and Works

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the South Wales Daily Post, only to leave under pressure 18 months later. Thomas continued to work as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and continued to add to his notebooks, amassing 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

Thomas’s first book, 18 Poems, appeared in 1934, and it announced a strikingly new and individual, if not always comprehensible, the voice in English poetry. His original style was further developed in Twenty-Five Poems (1936) and The Map of Love (1939). Thomas’s work, in its overtly emotional impact, its insistence on the importance of sound and rhythm, its primitivism, and the tensions between its biblical echoes and its sexual imagery, owed more to his Welsh background than to the prevailing taste in English literature for grim social commentary. Therein lay its originality. The poetry written up to 1939 is concerned with introspective, obsessive, sexual, and religious currents of feeling; and Thomas seems to be arguing rhetorically with himself on the subjects of sex and death, sin and redemption, the natural processes, creation, and decay. The writing shows prodigious energy, but the final effect is sometimes obscure or diffuse.

By the late 1930s, Thomas was embraced as the “poetic herald” for a group of English poets, the New Apocalyptics. Thomas refused to align himself with them and declined to sign their manifesto. He later stated that he believed they were “intellectual muckpots leaning on a theory”. Despite this, many of the group, including Henry Treece, modelled their work on Thomas. During the politically charged atmosphere of the 1930s, Thomas’s sympathies were very much with the radical left, to the point of holding close links with the communists, as well as decidedly pacifist and anti-fascist. He was a supporter of the left-wing No More War Movement and boasted about participating in demonstrations against the British Union of Fascists.

To support his growing family, Thomas was forced to write radio scripts for the Ministry of Information (Great Britain’s information services) and documentaries for the British government. He also served as an aircraft gunner during World War II (1939–45; a war fought between Germany, Japan, and Italy, the Axis powers; and England, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States, the Allies). After the war, he became a commentator on poetry for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

In 1950 Thomas made the first of three lecture tours through the United States the others were in 1952 and 1953 in which he gave more than one hundred poetry readings. In these appearances he half recited, half sang the lines in his “Welsh singing” voice.

Thereafter, Thomas concentrated on writing poems while supporting himself by freelance journalism. Sometimes now, he also tried his hand at acting and joined an amateur dramatic group, which is now known as Swansea Little Theatre. It was also during this period that he befriended Bert Trick, an amateur poet, and grocer, who inspired him to write a poem on immortality, resulting in his famous poem, ‘And death shall have no dominion.’ It was written in April 1933 and published in ‘New English Weekly ‘on May 8.

‘Before I Knocked’, ‘The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower’ and ‘Light breaks where no sun shines’ are a few other popular poems of this period. Among these, the last mentioned poem, published in ‘The Listener’ in 1934, was noticed by T. S. Eliot, Geoffrey Grigson, and Stephen Spender.

In 1939, a collection of 16 poems and seven of the 20 short stories published by Thomas in magazines since 1934, appeared as The Map of Love. Ten stories in his next book, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (1940), were based less on lavish fantasy than those in The Map of Love and more on real-life romances featuring himself in Wales. Sales of both books were poor, resulting in Thomas living on meagre fees from writing and reviewing. At this time he borrowed heavily from friends and acquaintances. Hounded by creditors, Thomas and his family left Laugharne in July 1940 and moved to the home of critic John Davenport in Marshfield, Gloucestershire. There Thomas collaborated with Davenport on the satire The Death of the King’s Canary, though due to fears of libel the work was not published until 1976.

On 4 April 1940, he published his fourth book, ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog’, containing stories, which were mostly autobiographical, based in Swansea. Unfortunately, both these books were initially commercial failures. Therefore, Thomas was forced to depend on his meager income from writing and reviewing. Thomas loved the wild landscape of Wales, and he put much of his childhood and youth into these stories. He published two more new collections of poetry, both of which contained some of his finest work: Deaths and Entrances (1946) and In Country Sleep (1951). Collected Poems, 1934–1953 (1953) contains all of his poetry that he wished to preserve.

The theme of all of Thomas’s poetry is the celebration of the divine (godly) purpose he saw in all human and natural processes. The cycle of birth and flowering and death, of love and death, are also found throughout his poems. He celebrated life in the seas and fields and hills and towns of his native Wales. In some of his shorter poems, he sought to recapture a child’s innocent vision of the world.

Thomas was passionately dedicated to his “sullen art,” and he was a competent, finished, and occasionally complex craftsman. He made, for example, more than two hundred versions of “Fern Hill” before he was satisfied with it. His early poems are relatively mysterious and complex in sense but simple and obvious in a pattern. His later poems, on the other hand, are simple in sense but complex in sounds.

Thomas also makes extensive use of Christian myth and symbolism and often sounds a note of formal ritual and incantation in his poems. The re-creation of childhood experience produces a visionary, mystical poetry in which the landscapes of youth and infancy assume the holiness of the first Eden (“Poem in October,” “Fern Hill”); for Thomas, childhood, with its intimations of immortality, is a state of innocence and grace. But the rhapsodic lilt and music of the later verse derive from a complex technical discipline so that Thomas’ absorption in his craft produces verbal harmonies that are unique in English poetry.

In February 1941, Swansea was bombed by the Luftwaffe in a “three nights’ blitz”. Castle Street was one of many streets that suffered badly; rows of shops, including the Kardomah Café, were destroyed. Thomas walked through the bombed-out shell of the town center with his friend Bert Trick. Upset at the sight, he concluded: “Our Swansea is dead”. Soon after the bombing raids, Thomas wrote a radio play, Return Journey Home, which described the café as being “razed to the snow”. The play was first broadcast on 15 June 1947. The Kardomah Café reopened on Portland Street after the war.

In 1944, as the threat of bombing by the Germans began to increase, he moved his family first to Blaen Cwm near Llangain and then to New Quay. There is the month of November, he finished his well-known poem, ‘Vision and Prayer.’ The following year, he wrote ‘Holy Spring.’

Meanwhile, the London or London-based atmosphere became increasingly dangerous and uncongenial both to Thomas and to his wife. As early as 1946 he was talking of emigrating to the United States, and in 1947 he had what would seem to be a nervous breakdown but refused psychiatric assistance. He moved to Oxford, where he was given a cottage by the distinguished historian A.J.P. Taylor. His trips to London, however, principally in connection with his BBC work, were grueling, exhausting, and increasingly alcoholic.

Later on from late 1946, he began to take part in BBC’s ‘Third Programme’, appearing in plays like ‘Comus’, ‘Paradise Lost’ and ‘Agamemnon.’ Very soon, he became a popular radio voice and a celebrity. Also in 1946, he had his fifth book of poetry published. Titled, ‘Deaths and Entrances’, it dealt mainly with the effects of World War II and soon became very popular.

In May 1949 Thomas and his family moved to his final home, the Boat House at Laugharne, purchased for him at a cost of £2,500 in April 1949 by Margaret Taylor. Thomas acquired a garage a hundred yards from the house on a cliff ledge which he turned into his writing shed, and where he wrote several of his most acclaimed poems. Just before moving into there, Thomas rented “Pelican House” opposite his regular drinking den, Brown’s Hotel, for his parents who lived there from 1949 until 1953. It was there that his father died and the funeral was held.

Thomas’s poetic output was not large. He wrote only six poems in the last six years of his life. A grueling lecture schedule greatly slowed his literary output in these years. His belief that he would die young led him to create “instant Dylan” the persona of the wild young Welsh bard, damned by drink and women, that he believed his public wanted. When he was thirty-five years old, he described himself as “old, small, dark, intelligent, and darting-doting-dotting eyed … balding and toothless.”

In 1950, he was invited to New York and there he embarked on a three-month tour of arts centers and campuses. Although it was a highly successful tour both critically and financially, he still continued to drink heavily and turned out to be a difficult guest.

On returning to England, he continued with his literary pursuits and in 1952, published two more books, ‘In Country Sleep and Other Poems’ and also a collection of his old poems ‘Collected Poems, 1934–1952’. Also in the same year, he took his second trip to the U.S.A.

Thomas undertook a second tour of the United States in 1952, this time with Caitlin after she had discovered he had been unfaithful on his earlier trip. They drank heavily, and Thomas began to suffer from gout and lung problems. The second tour was the most intensive of the four, taking in 46 engagements. The trip also resulted in Thomas recording his first poetry to vinyl, which Caedmon Records released in America later that year. One of his works recorded during this time, A Child’s Christmas in Wales, became his most popular prose work in America. The original 1952 recording of A Child’s Christmas in Wales was a 2008 selection for the United States National Recording Registry, stating that it is “credited with launching the audiobook industry in the United States”.

During Thomas’s visit to the United States in 1953, he was scheduled to read his own and other poetry in some forty university towns throughout the country. He also intended to work on the libretto (text) of an opera for Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) in the latter’s California home. Thomas celebrated his thirty-ninth birthday in New York City in a mood of gay exhilaration, following the extraordinary success of his just-published Collected Poems. The festivities ended in his collapse and illness.

Thomas was passionately dedicated to his “sullen art,” and he was a competent, finished, and occasionally complex craftsman. He made, for example, more than two hundred versions of “Fern Hill” before he was satisfied with it. His early poems are relatively mysterious and complex in sense but simple and obvious in the pattern. His later poems, on the other hand, are simple in sense but complex in sounds.

In 1953, he undertook his third trip to America. On his return, he wrote ‘Under Milk Wood’ for BBC and sent the manuscript to the producer on 15 October 1953. On 19 October the same year, he left for the United States again, never to return.

Awards and Honor

Dylan Thomas’ last collection ‘Collected Poems, 1934–1952’ won the Foyle poetry prize.

The Boathouse where Thomas spent his last years was turned into a museum. Housing many of his memorabilia and some of his original furniture, it receives about 15,000 visitors every year.

Apart from a number of monuments, Swansea, the city of his birth, is home to Dylan Thomas Theatre and Dylan Thomas Center. Besides, Dylan Thomas Prize and Dylan Thomas Screenplay Award have been established in his honor.

Death and Legacy

(Thomas’s grave at the churchyard in Laugharne)

Thomas arrived in New York on 20 October 1953 to undertake another tour of poetry-reading and talks, organized by Brinnin. Although he complained of chest trouble and gout while still in Britain, there is no record that he received medical treatment for either condition. He was admitted to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he died on 9 November 1953. His body was brought back to Laugharne for burial.

He was comatose, and his medical notes state that the “impression upon admission was acute alcoholic encephalopathy damage to the brain by alcohol, for which the patient was treated without response”. Caitlin flew to America the following day and was taken to the hospital, by which time a tracheotomy had been performed. Her reported first words were, “Is the bloody man dead yet?” She was allowed to see Thomas only for 40 minutes in the morning but returned in the afternoon and, in a drunken rage, threatened to kill Brinnin. When she became uncontrollable, she was put in a straitjacket and committed, by Feltenstein, to the River Crest private psychiatric detox clinic on Long Island.

Although the autopsy indicated that pneumonia was the primary cause of death, many believed it to have been alcohol-related, because he had been engaged in a drinking binge prior to his expiration. It was later revealed that in the hours before he was taken to the hospital, Thomas, who had complained of breathing difficulties, was administered several doses of morphine by a personal physician. It is possible that the drug fatally depressed his already-impaired respiratory system.

Thomas died intestate with assets to the value of £100. His body was brought back to Wales for burial in the village churchyard at Laugharne. Thomas’s funeral, which Brinnin did not attend, took place at St Martin’s Church in Laugharne on 24 November. Thomas’s coffin was carried by six friends from the village. Caitlin, without her customary hat, walked behind the coffin, with his childhood friend Daniel Jones at her arm and her mother by her side. The procession to the church was filmed and the wake took place at Brown’s Hotel. Thomas’s obituary in The Times was written by fellow poet and long-time friend Vernon Watkins.

Under Milk Wood, a radio play commissioned by the BBC (published 1954), was Thomas’s last completed work. This poem-play is not a drama but a parade of strange, outrageous, and charming Welsh villagers. During the twenty-four hours presented in the play, the characters remember and ponder the casual and crucial moments of their lives. Adventures in the Skin Trade and Other Stories (1955) contains all the uncollected stories and shows the wit and humor that made Thomas an enchanting companion.

In 1995 Ty Llên (later the Dylan Thomas Centre) was established in Swansea. The building, a former Guildhall, was largely converted into space for businesses in 2012, but a 2014 endowment allowed for a significant expansion of the permanent collection of Thomas memorabilia housed there.

In 2014, to celebrate the centenary of Thomas’s birth, the British Council Wales undertook a year-long programme of cultural and educational works. Highlights included a touring replica of Thomas’s work shed, Sir Peter Blake’s exhibition of illustrations based on Under Milk Wood and a 36-hour marathon of readings, which included Michael Sheen and Sir Ian McKellen performing Thomas’s work. The Royal Patron of The Dylan Thomas 100 Festival was Charles, Prince of Wales, who made a recording of Fern Hill for the event.

Information Source: