Al-Maʿarri – Muslim Philosopher (973-1057)

Name: Abul ʿAla Al-Maʿarri

Arabic: أبو العلاء المعري

Born: December 973

Place of born: Maarrat al-Nu’man, Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo

Died: May 1057 (aged 83)

Place of died: Maarrat al-Nu’man, Mirdasid Emirate of Aleppo

School: Arabic literature

Main interests: Poetry, Skepticism, Rationalism, Ethics, Pessimism

Early Life

Al-Maʿarrī, in full Abū al-ʿAlāʾ Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Maʿarrī was born on December 973, in Maʿarrat al-Nuʿmān, near Aleppo, Syria. He was a great Arab poet, known for his virtuosity and for the originality and pessimism of his vision.

He was a controversial rationalist of his time, attacking the dogmas of religion rejecting the claim that Islam or any other religion possessed the truths they claim and considered the speech of prophets as a lie (literally, “forge”) and “impossible” to be true. He was equally sarcastic towards the religions of Muslims, Jews, and Christians. He was also a vegan who argued for animal rights.

He was pessimistic about life, describing himself as “a double prisoner” of blindness and isolation.

He was a strict vegetarian, writing “do not desire as food the flesh of slaughtered animals.” Al-Maʿarri held an anti-natalist view, in line with his general pessimism, suggesting that children should not be born to spare them of the pains of life.

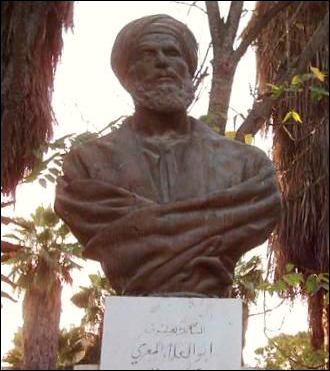

Al-Maʿarri wrote three main works that were popular in his time. Among his works are “The Tinder Spark”, “Unnecessary Necessity”, and “The Epistle of Forgiveness” which may be considered a precursor to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Al-Maʿarri never married and died at the age of 83 in the city where he was born, Maarrat al-Nuʿman. In 2013, a statue of Al-Maʿarri located in his Syrian hometown was beheaded by jihadists from the Al-Nusra Front.

Personal and Educational Career

Abul Ala was born in Maʿarra, modern Maarrat al-Nuʿman, Syria, near the city of Aleppo, in December 973. Born in the Syrian city of Maʿarra, he studied in nearby Aleppo, then in Tripoli and Antioch. Producing popular poems in Baghdad, he nevertheless refused to sell his texts. In 1010, he returned to Syria after his mother began declining in health, and continued writing which gained him local respect.

At his time, the city was part of the Abbasid Caliphate, the third Islamic caliphate, and was during the Golden Age of Islam. He was a member of the Banu Sulayman, a notable family of Maʿarra, belonging to the larger Tanukh tribe. His paternal great-great-grandfather had been the city’s first qadi. Some members of the Bany Sulayman had also been noted as good poets. He lost his eyesight at the age of four due to smallpox.

He lost his eyesight at the age of four due to smallpox. His later pessimism may be explained by his virtual blindness. Later in his life, he regarded himself as “a double prisoner” which referred to both this blindness and the general isolation that he felt during his life.

He started his career as a poet at an early age, at about 11 or 12 years old. He was educated at first in Maʿarra and Aleppo, later also in Antioch and other Syrian cities. Among his teachers in Aleppo were companions from the circle of Ibn Khalawayh. This grammarian and Islamic scholar had died in 980/1 AD, when Al-Maʿarri was still a child. Al-Maʿarri nevertheless laments the loss of Ibn Ḵh̲ālawayh in strong terms in a poem of his Risālat al-ghufrān. Al-Qifti reports that when on his way to Tripoli, Al-Maʿarri visited a Christian monastery near Latakia where he listened to debates about Hellenic philosophy, which planted in him the seeds of his later skepticism and irreligiosity; but other historians such as Ibn al-Adim deny that he had been exposed to any theology other than Islamic doctrine.

He also spent eighteen months at Baghdad, where he was well received in the literary salons of the time. He returned to his native town of Maʿarra in about 1010 blaming his return on a lack of money and hearing that his mother was ill and she died before he arrived.

He remained in Maʿarra for the rest of his life, where he opted for an ascetic lifestyle, refusing to sell his poems, living in seclusion and observing a strict vegetarian diet. His personal confinement to his house was only broken one time when violence had struck his town. Though he was confined, he lived out his later years continuing his work and collaborating with others. He enjoyed great respect and attracted many students locally, as well as actively holding correspondence with scholars abroad. Despite his intentions of living a secluded lifestyle, in his seventies, he became rich and was the most revered person in his area. Al-Maʿarri never married.

Career

Al-Maʿarri taught that religion was a “fable invented by the ancients”, worthless except for those who exploit the credulous masses.

Do not suppose the statements of the prophets to be true; they are all fabrications. Men lived comfortably till they came and spoiled life. The sacred books are only such a set of idle tales as any age could have and indeed did actually produce.

He was a skeptic in his beliefs who denounced superstition and dogmatism in religion. This, along with his general negative view on life, has made him described as a pessimistic freethinker. One of the recurring themes of his philosophy was the right of reason against the claims of custom, tradition, and authority.

Al-Maʿarri criticized many of the dogmas of Islam, such as the Hajj, which he called “a paganʿs journey.” He rejected claims of any divine revelation and his creed was that of a philosopher and ascetic, for whom reason provides a moral guide, and virtue is its own reward.

His religious skepticism and positively anti-religious views extended beyond Islam and also toward Judaism and Christianity. Al-Maʿarri remarked that monks in their cloisters or devotees in their mosques were blindly following the beliefs of their locality: if they were born among Magians or Sabians they would have become Magians or Sabians. Encapsulating his view on organized religion, he once stated, “The inhabitants of the earth are of two sorts: those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains.”

Al-Maʿarri’s fundamental pessimism is expressed in his anti-natalist recommendation that no children should be begotten, so as to spare them the pains of life. In an elegy composed by him over the loss of a relative, he combines his grief with observations on the ephemerality of this life:

Soften your tread. Methinks the earth’s surface is but bodies of the dead,

Walk slowly in the air, so you do not trample on the remains of God’s servants.

Even on al-Maʿarri’s epitaph, he wanted it written that his life was a wrong done by his father and not one that was done by himself.

Al-Maʿarri was an ascetic, renouncing worldly desires and living secluded from others while producing his works. He opposed all forms of violence. In Baghdad, while being well received, he decided not to sell his texts, which made it difficult for him to live. This ascetic lifestyle has been compared to similar thought in India during his time.

In al-Maʿarri’s later years, he became a strict vegan, neither consuming meat, nor any other animal products. He wrote:

And do not desire as food the flesh of slaughtered animals,

Or the white milk of mothers who intended its pure draught for their young, not noble ladies.

I washed my hands of all this; and wish that I Perceived my way before my hair went gray!

An early collection of his poems appeared as “The Tinder Spark” (Saqṭ al-zand; سقط الزند). The collection of poems included praise of notable people of Aleppo and the Hamdanid ruler Sa’d al-Dawla. It gained great popularity and established his reputation as a poet. A few poems in the collection were about armor.

A second, more original collection appeared under the title “Unnecessary Necessity” (Luzūm mā lam yalzam لزوم ما لا يلزم أو اللزوميات ), which is how Al-Maʿarri saw the business of living; also Luzūmīyāt “Necessities”, alluding to the unnecessary complexity of the rhyme scheme used.

His third famous work is a work of prose known as “The Epistle of Forgiveness” (Risālat al-ghufrān رسالة الغفران). The work was written as a direct response to the Arabic poet Ibn al-Qarih, whom Al-Maʿarri mocks for his religious views. In this work, the poet visits paradise and meets the Arab poets of the pagan period, contrary to Muslim doctrine which holds that only those who believe in God can find salvation (Quran 4:48). Because of the aspect of conversing with the deceased in paradise, the Resalat Al-Ghufran has been compared to the Divine Comedy of Dante which came hundreds of years after. The work has also been noted to be similar to Ibn Shuhayd’s Risala al-tawabi’ wa al-zawabi though there is no evidence that Al-Maʿarri was inspired by Ibn Shahayd nor is there any evidence that Dante was inspired by Al-Maʿarri. Algeria reportedly banned “The Epistle” from the International Book Fair held in Algiers in 2007.

“Paragraphs and Periods” (Al-Fuṣūl wa al-ghāyāt) is a collection of homilies. The work has also been called a parody of the Quran.

Al-Maʿarri is controversial even today as he was skeptical of Islam, the dominant religion of the Arab World. In 2013, almost a thousand years after his death, the al-Nusra Front, a branch of al-Qaeda, beheaded a statue of Al-Maʿarri during the civil war in Syria. The statue had been crafted by the sculptor Fathi Muhammad. The motive behind the beheading is disputed; theories range from the fact that he was a heretic to the fact that he is believed by some to be related to the Assad family.

Still, al-Maʿarri is sometimes referred to as one of the greatest classical Arab poets. Some have drawn connections between him and the Roman poet Titus Lucretius Carus, citing how progressive their views were compared to the time in which they lived.

Death

He was died in May 1057 in his hometown, Maarrat al-Nu’man, Mirdasid Emirate of Aleppo.

Honours

Al-Maʿarri held and expressed an irreligious worldview which was met with controversy, but in spite of it, he is regarded as one of the greatest classical Arabic poets.

In 2013, almost a thousand years after his death, the al-Nusra Front, a branch of al-Qaeda, beheaded a statue of Al-Maʿarri during the civil war in Syria. The statue had been crafted by the sculptor Fathi Muhammad.

“Paragraphs and Periods” (Al-Fuṣūl wa al-ghāyāt) is a collection of homilies. The work has also been called a parody of the Quran.