Mary Shelley

(English novelist, Short story writer, Dramatist, Essayist, Biographer, and Travel writer)

Full name: Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin

Date of birth: 30 August 1797

Place of birth: Somers Town, London, England

Date of death: 1 February 1851 (aged 53)

Place of death: Chester Square, London, England

Occupation: Writer

Period: Romantic / Gothic

Spouse: Percy Bysshe Shelley (m. 1816–1822)

Children: Percy Florence Shelley, Clara Everina Shelley, William Shelley

Early Life

Mary Wollestonecraft (Godwin) Shelley was born on August 30, 1797 in London, England. She was an English novelist, short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). She also edited and promoted the works of her husband, the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her father was the political philosopher William Godwin, and her mother was the philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft.

Until the 1970s, Mary Shelley was known mainly for her efforts to publish her husband’s works and for her novel Frankenstein, which remains widely read and has inspired many theatrical and film adaptations. Recent scholarship has yielded a more comprehensive view of Mary Shelley’s achievements. Scholars have shown increasing interest in her literary output, particularly in her novels, which include the historical novels Valperga (1823) and Perkin Warbeck (1830), the apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826), and her final two novels, Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837). Studies of her lesser-known works, such as the travel book Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844) and the biographical articles for Dionysius Lardner’s Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829–46), support the growing view that Mary Shelley remained a political radical throughout her life. Mary Shelley’s works often argue that cooperation and sympathy, particularly as practised by women in the family, were the ways to reform civil society. This view was a direct challenge to the individualistic Romantic ethos promoted by Percy Shelley and the Enlightenment political theories articulated by her father, William Godwin.

Childhood and Educational Life

Mary Shelley was born on August 30, 1797, in London, England. She was the daughter of philosopher and political writer William Godwin and famed feminist Mary Wollstonecraft—the author of The Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Sadly for Shelley, she never really knew her mother who died shortly after her birth. Her father William Godwin was left to care for Shelley and her older half-sister Fanny Imlay. Imlay was Wollstonecraft’s daughter from an affair she had with a soldier.

Mary spent some time at a dame school. However Mary was mainly educated at home. She was a highly intelligent woman and she studied history, literature and the Bible. Mary learned Latin, French and Italian and Greek.

Personal Life

In 1812 Mary met Percy Bysshe Shelley for the first time. In 1814 she eloped with him. Mary Shelley had a daughter in February 1815 but the child died after a few days. However in January 1816 Mary gave birth to a son named William. In may 1816 Mary, Percy and their son traveled to Geneva. While there Mary was inspired to write the novel Frankenstein. It was published in 1818. Mary married Percy on 30 December 1816 in London. On 2 September 1817 Mary gave birth to another daughter. This one was called Clara. Unfortunately Clara Shelley died on 24 September 1818. Mary’s son William died on 7 June 1819. However on 12 November while in Florence Mary gave birth to another son, Percy Florence Shelley. He was the couple’s only surviving child. Tragedy struck again on 8 July 1822 Percy Shelley drowned.

Mary’s life was rocked by another tragedy in 1822 when her husband drowned. He had been out sailing with a friend in the Gulf of Spezia.

Writing Career

Mary’s story, the best of the group, was so frightening to Byron that he ran “shrieking in horror” from the room. Frankenstein was published in 1818. There are differences in the 1818, 1823, and 1831 editions, and Mary Shelley wrote, “I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world.” She wrote that the preface to the first edition was Percy’s work “as far as I can recollect.” James Rieger concluded Percy’s “assistance at every point in the book’s manufacture was so extensive that one hardly knows whether to regard him as editor or minor collaborator”, while Anne K. Mellor later argued Percy only “made many technical corrections and several times clarified the narrative and thematic continuity of the text.” Charles E. Robinson, editor of a facsimile edition of the Frankenstein manuscripts, concluded that Percy’s contributions to the book “were no more than what most publishers’ editors have provided new (or old) authors or, in fact, what colleagues have provided to each other after reading each other’s works in progress.”

Frankenstein, like much Gothic fiction of the period, mixes a visceral and alienating subject matter with speculative and thought-provoking themes. Rather than focusing on the twists and turns of the plot, however, the novel foregrounds the mental and moral struggles of the protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, and Shelley imbues the text with her own brand of politicised Romanticism, one that criticised the individualism and egotism of traditional Romanticism. Victor Frankenstein is like Satan in Paradise Lost, and Prometheus: he rebels against tradition; he creates life; and he shapes his own destiny. These traits are not portrayed positively; as Blumberg writes, “his relentless ambition is a self-delusion, clothed as quest for truth”. He must abandon his family to fulfill his ambition

Early in the summer of 1817, Mary Shelley finished Frankenstein, which was published anonymously in January 1818. Reviewers and readers assumed that Percy Shelley was the author, since the book was published with his preface and dedicated to his political hero William Godwin.

Made a widow at age 24, Mary Shelley worked hard to support herself and her son. She wrote several more novels, including Valperga and the science fiction tale The Last Man (1826). She also devoted herself to promoting her husband’s poetry and preserving his place in literary history. For several years, Shelley faced some opposition from her late husband’s father who had always disapproved his son’s bohemian lifestyle.

As literary scholar Kari Lokke writes, The Last Man, more so than Frankenstein, “in its refusal to place humanity at the center of the universe, its questioning of our privileged position in relation to nature … constitutes a profound and prophetic challenge to Western humanism.” Specifically, Mary Shelley’s allusions to what radicals believed was a failed revolution in France and the Godwinian, Wollstonecraftian, and Burkean responses to it, challenge “Enlightenment faith in the inevitability of progress through collective efforts”. As in Frankenstein, Shelley “offers a profoundly disenchanted commentary on the age of revolution, which ends in a total rejection of the progressive ideals of her own generation”. Not only does she reject these Enlightenment political ideals, but she also rejects the Romantic notion that the poetic or literary imagination can offer an alternative.

During the period 1827–40, Mary Shelley was busy as an editor and writer. She wrote the novels The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835), and Falkner (1837). She contributed five volumes of Lives of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and French authors to Lardner’s Cabinet Cyclopaedia. She also wrote stories for ladies’ magazines. She was still helping to support her father, and they looked out for publishers for each other. In 1830, she sold the copyright for a new edition of Frankenstein for £60 to Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley for their new Standard Novels series. In the summer of 1838 Edward Moxon, the publisher of Tennyson and the son-in-law of Charles Lamb, proposed publishing a collected works of Percy Shelley. Mary was paid £500 to edit the Poetical Works (1838), which Sir Timothy insisted should not include a biography. Mary found a way to tell the story of Percy’s life, nonetheless: she included extensive biographical notes about the poems.

In 1828, she met and flirted with the French writer Prosper Mérimée, but her one surviving letter to him appears to be a deflection of his declaration of love. She was delighted when her old friend from Italy, Edward Trelawny, returned to England, and they joked about marriage in their letters. Their friendship had altered, however, following her refusal to cooperate with his proposed biography of Percy Shelley; and he later reacted angrily to her omission of the atheistic section of Queen Mab from Percy Shelley’s poems. Oblique references in her journals, from the early 1830s until the early 1840s, suggest that Mary Shelley had feelings for the radical politician Aubrey Beauclerk, who may have disappointed her by twice marrying others.

Death and Legacy

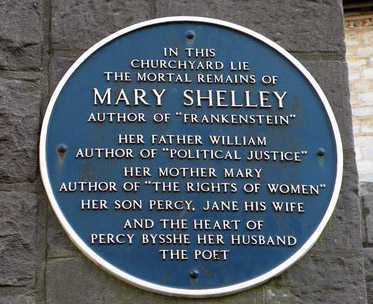

Mary Shelley died of brain cancer on February 1, 1851, at age 53, in London, England. She was buried at St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth, laid to rest with the cremated remains of her late husband’s heart. After her death, her son Percy and daughter-in-law Jane had Mary Shelley’s parents exhumed from St. Pancras Cemetery in London (which had fallen into neglect over time) and had them reinterred beside Mary at the family’s tomb in St. Peter’s in Bournemouth.

It was roughly a century after her passing that one of her novels, Mathilde, was finally released in the 1950s. Her lasting legacy, however, remains the classic tale of Frankenstein. This struggle between a monster and its creator has been an enduring part of popular culture. In 1994, Kenneth Branagh directed and starred in a film adaptation of Shelley’s novel. The film also starred Robert De Niro, Tom Hulce and Helena Bonham Carter. Her work has also inspired some spoofs, such as Young Frankenstein starring Gene Wilder. Shelley’s monster lives on in such modern thrillers as I, Frankenstein (2013) as well.