Cupra Marittima is a small town located in the Marche region of Italy, known for its scenic coastal views and beaches. It’s a popular vacation spot for tourists, offering a variety of outdoor activities such as swimming, hiking, and fishing. The town is today a sleepy seaside town but it was once a thriving and powerful outpost of the Roman Empire.

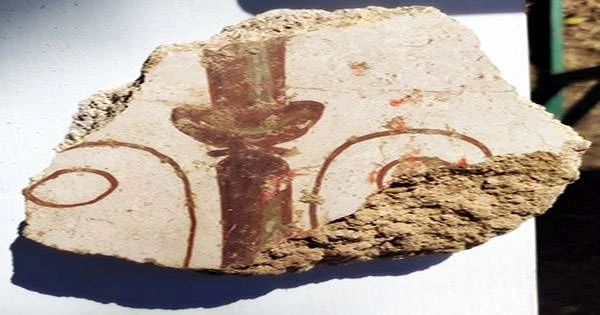

Close to the pristine beaches of the Adriatic coast lie the ruins of the ancient Cupra temple, where a new discovery has come to light. The frescoed walls and ceiling of the 2,000-year-old temple were partially discovered last week. They were painted in blue, yellow, red, black, and green tones and embellished with floral garlands, candelabra, and little palm trees.

Finding ancient Roman temples with the interiors “still covered in paintings” is “extremely rare,” said archaeologist Marco Giglio, the site’s research project coordinator and a professor at the University of Naples L’Orientale.

“It’s the first time that the ruins of a shrine painted with such a wide palette of colors in an incredibly well-preserved state and with such rich, elaborate decorations has been unearthed,” he claimed in a phone interview, adding: “Once we have cleaned and analyzed all the 100 fragments found and pieced them together, we hope it will give us a complete picture of what the temple once looked like.”

Giglio expects that the discovery will reveal fresh information on Roman engineering practices. Researcher’s understanding of the city’s regional economy may be furthered by examining the walls’ recurrent decorative themes.

“The chronology of the different styles and decorative elements could tell (us) a lot about the artisan shops active at the time,” he said. “And the patterns and motifs could highlight whether it was the work of just one atelier or more.”

Unusual painting style

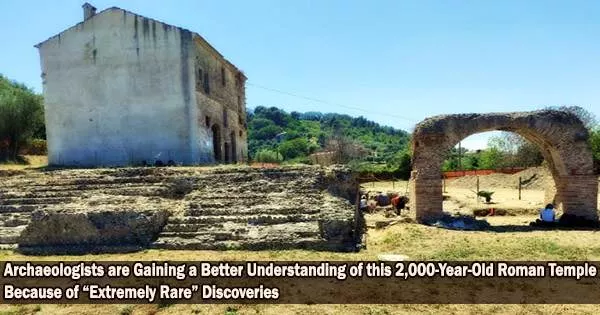

The Cupra temple was the spiritual center of a strategically and economically significant city that assisted the Romans in gaining control of the Adriatic coast and its maritime trade routes. It was constructed in the beginning of the first century AD. Excavation began in July and is being led by the University of Naples L’Orientale and Cupra Marittima’s town council, which oversees the archaeological park where the old city’s ruins are situated.

“Unusually, the newly discovered wall paintings appear to have been created in the so-called Third Pompeian (or “ornamental”) style typically used to decorate rich households in Pompeii and Rome, rather than religious structures,” according to Giglio.

The lower portion of the temple’s walls were supposedly painted yellow, and the original sanctuary’s ceiling was considered to have been sky blue. Images of candelabra and garlands were used to divide the red, black, and yellow squares, and horizontal green streaks of color ran down the walls.

“Recovering intact ancient wall paintings like these is very rare. Paint is hard to preserve across time due to humidity, and it’s also very hard to dig out correctly during an excavation,” said Ilaria Benetti, an archaeologist from Pisa and Livorno provinces’ Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape in a phone interview.

“The incredible state of preservation and integrity of the frescoed parts, and the extremely rich color palette used particularly the bright sky-blue and pinkish-red stand out as quite exceptional when compared to the traditional red paint normally used in ancient times, thus suggesting it was a lavish shrine,” added Benetti, who is a frescoes expert but was not directly involved in the excavation.

Giglio added: “The sky-blue color is very rare for ceilings, which leads us to believe it was meant to indicate the celestial vault and that the shrine was built to honor a goddess.”

Although the temple shares a name with Cupra, an Etruscan goddess later incorporated into Roman religion, archaeologists have yet to determine which cult was associated to the shrine. A large statue of a goddess was likely kept in the main cell for worshippers, said Giglio.

The podium and a stairway leading to the entrance have survived, however the majority of the temple was eventually destroyed. Archaeologists started excavating earlier in the summer, but by the time they finished, the rest of the shrine had been reduced to a mass of rubble that was one meter (more than three feet) below the surface.

The temple underwent several radical changes after its foundation, making it harder for Gilgio’s team to envision what it originally looked like. In 127 AD, the Roman emperor Hadrian funded a complete overhaul of the shrine as he feared it might collapse due to structural damage caused by aging or natural disasters.

Hadrian is said to have ordered the painted walls to be removed and the building to be reinforced with marble. The original colorful parts were crushed during this operation, but they were later repurposed as the foundation for the new floors.

“That’s why the fragments recovered have been so well preserved, because their life was indeed short, roughly only a hundred years,” said Giglio, noting that this detail supports the idea that Roman builders recycled materials.

Later, Hadrian added semi-columns, roof dripstones with lion heads, and nine-meter high columns with artistic capitals, some of which have already been discovered in part. He also built two brick arches that still flank the temple site.

According to Giglio, Hadrian’s pagan masterpiece was later crushed to pieces starting from the 7th century. The marbles and columns were destroyed to be utilized as building materials, and the temple walls were destroyed by the end of the 19th century to create place for a country home that now looms above the shrine’s ruins.

“The house was actually built by incorporating part of the sanctuary’s walls, so we’re still trying to figure out whether it is best to restore it or take it down to recover the shrine in its entirety,” said Giglio.

With just one fifth of the temple site excavated thus far, the archaeologist said his team has had “just a taste” of what’s to come.

“Who knows what other decorations, patterns and elements could come to light?” he said. “It would be great that what we will unearth will lead to understand exactly how a construction site worked back in ancient Roman times.”