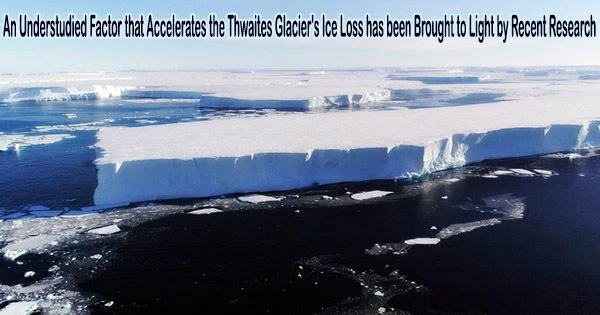

According to new research, the Thwaites Glacier’s 80-mile-wide stream of sliding ice is anticipated to move outward during the next 20 years, which might hasten the rate of ice loss in West Antarctica.

“It’s like a torrential river eating away at the riverbanks and widening in the process,” said senior study author Jenny Suckale, an assistant professor of geophysics at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

Thwaites Glacier is frequently referred to as the “doomsday glacier” due to its enormous size and ability to significantly raise sea levels. As the planet warms, billions of tons of ice might be lost into the Amundsen Sea and a channel for additional interior ice to easily flow to the shore.

The speed and thickness of the glacier have undoubtedly changed throughout ages, according to numerous earlier studies. The width of the glacier, which affects how much ice melts into the sea at any given time, has received less attention in research. Narrowing the main ice stream, or trunk, could stop ice loss by creating a new balance of forces, whereas widening it might make instability worse.

The new research, published March 7, 2023, in Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, uses numerical modeling to show how Thwaites Glacier’s rapid but uneven thinning could affect the eastern and western margins of its main trunk.

‘Relative stability’ remains possible

Paul Summers, a Ph.D. student in geophysics, and his team discovered that Thwaites Glacier’s observed thinning, along with changes to its surface’s slope and the environment at its base, makes both sides susceptible to moving a few miles outward during the following 20 years.

“We are considering relatively small changes in driving stress as would realistically occur in the coming two decades,” Summers and colleagues write. Yet even this subtle widening only about 2% of the glacier’s overall width could speed up ongoing ice loss.

“If the widening trend were to continue and were to accelerate, then we’d better know. It would mean that we would have to prepare for higher sea levels,” said Suckale, who is one of dozens of scientists working to understand the glacier and its response to climate change as part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

According to current models, sea levels may increase by only a few inches or even several feet in some areas during the next few decades.

“The policy actions you would have to consider from one extreme to the other are completely different,” Suckale said, ranging from improving flood management and drainage for infrastructure near shorelines to relocating entire coastal communities.

The “doomsday” scenario, however, is only one of “many, many possibilities,” said Suckale. “Stability is still well within the possibilities for Thwaites Glacier at least, relative stability.”

It would be necessary for scientists to revise current ice-loss models, which typically simplify the processes represented in the new research, to determine just how much Thwaites’s disintegration may speed as a result of its widening ice stream.

“We are trying to get at something more basic, which is the nature of the trend: widening, neutral, narrowing,” Suckale said.

Monitoring Thwaites like a coming storm

According to Summers, the research team anticipated that the glacier’s eastern shear margin would be most vulnerable to eroding away from the main trunk. They were astonished to see that the western barrier also seems prone to widening in some instances.

This finding highlights the need to intensify research on the western margin in addition to the work that is already being done on the eastern side, where Summers spent several weeks last year digging up seismic sensors and GPS systems and surveying the ice with ground penetrating radar as part of a team sent by the U.S. Antarctic Program.

In the past, models have attempted to forecast global sea levels hundreds of years in the future or fully represent the ice dynamics at Thwaites Glacier. Because researchers have been able to gather so few direct measurements of how ice sheets are changing in response to global warming, modeling ice sheet evolution and global sea level rise over these longer time scales produces dramatic predictions, according to Suckale. However, testing these predictions against actual data is extremely difficult.

“We are very intentionally focusing on the next two decades to enable testability and continued model development,” said Suckale.

The model’s output will next be compared to geophysical measurements of ongoing changes at two field locations along the eastern shear boundary and a third field site that is focused on what’s happening below the main trunk as the next stage.

“It’s kind of like weather predictions. You monitor the storms as they come in, and then you update your predictions and pass that information on. I think we need to monitor Thwaites and make sure we have ways to get that information into planners’ hands,” Suckale said. “We don’t need to hit the panic button, but we also can’t ignore this.”