A team led by the University of Maryland discovered that trees in Baltimore reflect both the city’s history of institutionalized racism and more recent efforts to combat environmental injustice. This study, funded by the National Science Foundation and the United States Department of Agriculture, is the most recent addition to the 25-year Baltimore Ecosystem study. The team’s findings were published in the journal Ecology on October 5, 2022.

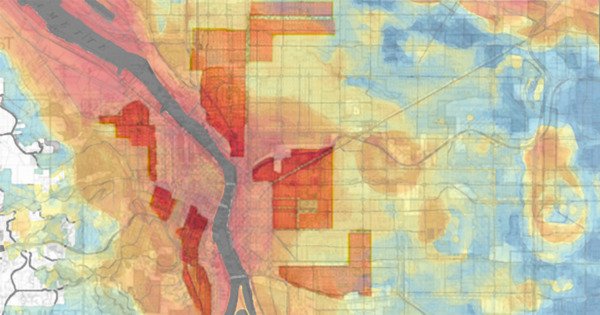

Researchers examined street trees in 36 Baltimore neighborhoods that were previously classified by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a New Deal program designed to increase homeownership. HOLC famously classified and color-coded neighborhoods based on perceived mortgage risk—green was labeled “best,” while red was labeled “hazardous.”

Often, the criteria used to classify neighborhoods was explicitly discriminatory; neighborhoods with high populations of racial and religious minorities as well as immigrants were more likely to be “redlined.” As a result, residents in those areas often experienced lower property values, resource investment by cities and wealth accumulation decades into the future.

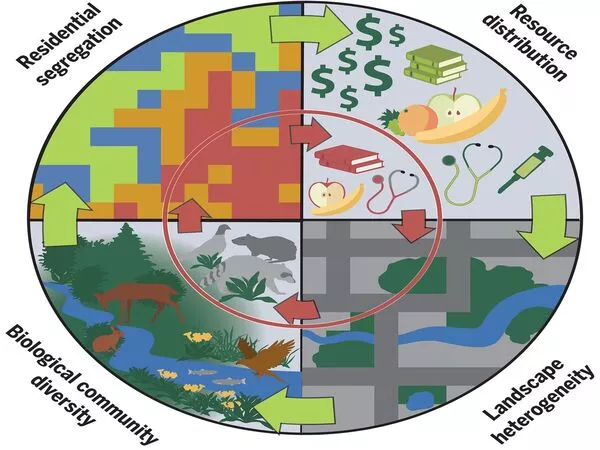

We discovered that previously redlined neighborhoods had consistently lower street tree diversity and were much less likely to have larger, older trees on a site. This is significant because differences in tree size and diversity affect the natural ecological services provided by trees, ultimately affecting the quality of life for residents living nearby.

Karin Burghardt

“We discovered that previously redlined neighborhoods had consistently lower street tree diversity and were much less likely to have larger, older trees on a site,” said Karin Burghardt, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of entomology at UMD. “This is significant because differences in tree size and diversity affect the natural ecological services provided by trees, ultimately affecting the quality of life for residents living nearby.”

“We discovered that previously redlined neighborhoods had consistently lower street tree diversity and were much less likely to have larger, older trees on a site,” said Karin Burghardt, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of entomology at UMD. “This is significant because differences in tree size and diversity affect the natural ecological services provided by trees, ultimately affecting the quality of life for residents living nearby.”

The researchers discovered that green, low-risk neighborhoods were nine times more likely to have larger and older trees than red, high-risk neighborhoods. Furthermore, trees in green neighborhoods were significantly more diverse, with more types of trees than in red neighborhoods. The researchers found that present-day street trees in Baltimore contained signatures of the 1937 HOLC loan risk classifications that had been based on racially discriminatory criteria.

“Larger, older trees have more canopy cover than smaller trees, which can have an impact on variables such as local heat islands, air quality, soil health, and even stormwater management. Similarly, greater tree diversity allows for greater resistance to invasive pest or disease outbreaks” Burghardt elaborated. “These differences in tree communities and size may help explain why red-lined areas have become associated with poorer health outcomes and shorter life expectancies for residents.”

On the other hand, the researchers observed a greater dominance of smaller, younger trees in formerly redlined neighborhoods, which could be evidence of Baltimore’s recent efforts to address neighborhood disparities.

Burghardt believes that Baltimore’s new sustainability goals, as well as efforts by city foresters and local tree-planting organizations, have likely resulted in an ongoing push to increase tree canopy cover and biodiversity in previously under-invested areas of the city. With this and similar movements, she believes that more people from all communities in Baltimore will be able to enjoy the natural benefits that trees provide while also contributing to the fight against climate change.

But the researchers did inject a note of caution; they discovered that these new communities of young trees planted in previously redlined neighborhoods were made up of fewer species than those in green areas and are heavily planted with a single species, red maple, across all previously redlined neighborhoods. While red maple is an adaptable, native tree species, the lessons of the massive loss of ash and elm trees from cities due to imported diseases and pests suggest that relying on one or a few species could decrease the resilience of these new urban forests in the future.

Finally, the research team hopes that their findings will assist Baltimore residents and policymakers in assessing current efforts to promote environmental justice and biodiversity. Data from HOLC color-coded maps and existing tree records indicate that more can be done to address Baltimore’s socioecological challenges, such as additional maintenance of young trees after planting and a greater emphasis on social investment in underserved communities.

“The negative effects of redlining can still be seen in today’s street tree communities,” Burghardt said. “However, our research shows that the people of Baltimore are making significant strides toward redressing environmental injustice.”