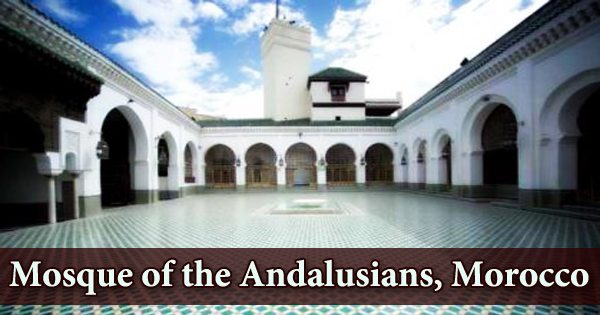

The Mosque of the Andalusians or Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (Arabic: مسجد الأندلسيين, romanized: Masjid al-Andalusiyyin), also known as the Andalusian Mosque, began as a small, simple neighborhood mosque before becoming the congregational mosque of the quarter in the 10th century, much like its counterpart Qarawiyyin Mosque. It is a significant historic mosque in Fes el Bali, Fez’s old medina neighborhood. The mosque was built between 859 and 860, making it one of Morocco’s oldest mosques. Andalusian architecture is a unique architectural treasure on the continent. The Roman and Islamic cultures determined the historical aspects of Andalusian architecture; both empires left their imprint through vaulted ceilings, pebbled courtyards, painted tiles, water features, and steady stone walls. The unusual and spectacular architectural heritage of Spain’s Islamic period (AD 711-1492) was particularly rich. Traditional Spanish farmhouses in a more complex form. The architectural treasures that this century left behind continue to gleam in fame and splendor in today’s world. The mosque sits in the midst of an area that was historically linked with Andalusi immigrants, and it gets its name from that. Since then, it has been rebuilt and enlarged multiple times. It is now one of the city’s most important landmarks and one of the few remaining Idrisid-era structures. The current look of the mosque is the product of several additions and reconstructions dating from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries. The minaret was added in the 10th/4th century by the Umayyad Caliph, while the north entrance was built by Almohad Caliph Muhammad al-Nasir (r. 1199–1213/ 595–610 AH). According to historical sources such as al-Jazna’i, Maryam bint Mohammed bin Abdullah al-Fihri (sister of Fatima al-Fihri, who founded the Qarawiyyin Mosque at the same time) founded the mosque in 859-860. The mosque’s construction was further supported by monies contributed by a group of local Andalusi inhabitants, who gave the mosque its current name. The “Moorish” arch, courtyard gardens with asymmetrical four-part division, and complex geometric and arabesque decorations in wood, stucco, and tilework are all unmistakable aspects of this rich and unique architectural style, often known as Moorish architecture.

The mosque had six aisles (or seven, according to al-Jazna’i) built by parallel rows of horseshoe arches supported on stone columns, according to the 12th-century Andalusian geographer Al-Bakri. It had a tiny sahn (courtyard) with a walnut tree and other trees planted in it. Unlike many later Moroccan mosques, the rows of arches ran east-west, parallel to rather than perpendicular to the southern qibla wall. The mosque’s doorway was built in the 13th century by artisans from Granada’s Nasrid kingdom. The entrance illustrates the strong cultural and political relations that existed between Fez and Islamic Spain, with its adornment of colorful glazed tiles and carved stucco, as well as its towering cornice of carved cedarwood. The minaret of the mosque was built in 956 by Abd al-Rahman III, the Umayyad caliph in Cordoba, and it still stands today. The local Zenata governor, Ahmed ibn Abi Said, an Umayyad vassal, oversaw the construction of both minarets, but it’s unclear how much personal participation Abd ar-Rahman III had in the project beyond giving the finances. The Almohad rebuilding added a massive northern gate, a fountain, a new entrance for the women’s prayer hall, and an apartment for the imam on a floor above the women’s prayer hall, in addition to enlarging the mosque’s layout. The masonry used in the Almohad building was of poor quality, according to Terrasse, and it had to be repaired and reconstructed in the late 13th century by the Marinids. In 1415 (816 AH), one of the last Marinid sultans, Abu Sa’id Uthman III, established a vast storage chamber at the back of the mosque with a cursive inscription panel over its double doors, which appears to have acted as a library. Similar to the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque, the mosque offered seven educational courses and had two libraries, making it the second most prominent mosque in Fez’s medina. Andalusia may be gone, but the wonderful Andalusian architecture will live on in images and drawings, if not in real life.