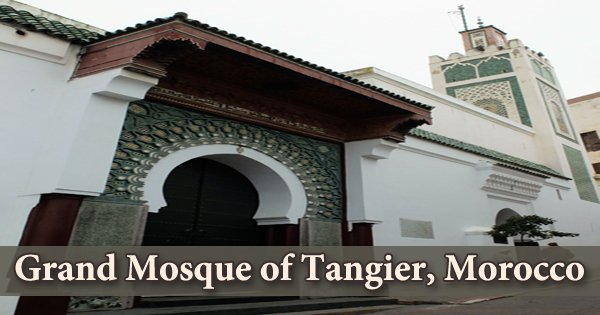

The Grand Mosque of Tangier is a nineteenth-century structure located in what was once the heart of Tangier’s medina; it is the city’s (Tangier, Morocco) traditional major mosque (Friday mosque). The mosque is on the site of many major religious structures from various civilizations that formerly occupied Tangier, the oldest of which dates back to a fifth-century Roman church. The church was transformed to a mosque by the Marinid Dynasty after the Muslim conquest of Tangier in the ninth century and remained thus until the late fifteenth century. While the present mosque was built during the Alaouite period in the early nineteenth century, the same location has been home to a succession of religious structures since Antiquity. During the centuries while Tangier was under Portuguese and English administration, the mosque was replaced by a church. While the present mosque was built during the Alaouite period in the early nineteenth century, the same location has been home to a succession of religious structures since Antiquity. During the centuries while Tangier was under Portuguese and English administration, the mosque was replaced by a church. The Muslim settlers went straight to the cathedral, which had formerly been the great mosque, to worship. Moulay Ismail gave the order to Ali ibn Abdallah Errifi, the new governor, to turn the structure into a mosque. Despite being a major symbol of the city’s restoration to Muslim authority, the new mosque was apparently quite primitive. Muslim visitors remarked about the lack of facilities. When the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Slimane saw it in 1815, he was allegedly so taken aback by its state that he ordered it to be entirely reconstructed. Artisans from outside Tangier were enlisted to assist with the project, which was finished in 1817-18. The mosque is rectangular in form, with the longitudinal axis turned 45 degrees counter-clockwise from the north-south meridian to accommodate the qibla. It is 34 meters long and 30 meters broad on the north-south axis and 30 meters wide on the east-west axis. The hypostyle-style prayer hall and courtyard within the mosque are enclosed by high external walls. The mosque is split into a grid of seven rows by seven columns by arcades. The main entrance to the mosque is located in the complex’s northwest elevation, on axis with the mihrab, which is located in the middle of the southeast wall. The mosque’s secondary entrances are on axis with the courtyard’s center, in the long northeast and southwest walls. The mosque’s minaret is placed in the northwest corner. This building is largely responsible for the mosque’s present appearance. The mosque was embellished or restored by subsequent Alaouite sultans, cementing its position as a symbol of the government’s significance in preserving religious orthodoxy in the face of various popular forms of religion centered upon Sufi marabouts. Important official announcements were made here in addition to the khutba, the weekly Friday sermon. The mosque was also a focal point for civic life and infrastructure in the city. It was in the Inner Market (previously the Roman Forum), following a pattern seen in other Moroccan and Islamic cities, where the city’s most significant or prestigious economic operations were held near the mosque.

The first row of arcades is covered when entering the mosque from the northwest wall, and inner walls perpendicular to the external mosque wall divide the middle three bays of the first row from the two outermost bays on either side of the entry. The internal walls surrounding the doorway and the ceiling both cease when the mosque’s courtyard begins as you pass through the second row of arcades. The courtyard is three bays long by three bays wide, or 11 meters wide by 13 meters long, and is bordered on all sides by covered arcades. At the middle of the courtyard is an ablution fountain. The covered prayer hall, which is seven arcade bays wide and three bays long, or 30 meters broad and 14 meters long, is located beyond the courtyard. The mihrab is located where the central arcade meets the qibla wall. A madrasa (school) was erected on the mosque’s northwestern side, across the street from its main entrance, in the 18th century under Sultan Muhammad ibn ‘Abdallah. A library and a funeral mosque (jama’ al-gna’iz, where funerary rites were conducted before the body was buried) were directly attached to the mosque, behind its southeastern wall (the qibla wall). Some of these facilities were administered and supported by the mosque’s habous (or waqf), which was a charitable trust that gathered money from different sources for the mosque’s care and that of its related establishments. The library and imam’s chamber are to the east of the mihrab along the qibla wall, while the funeral room is to the west. All of these rooms are behind the qibla wall, and hence outside the mosque’s main footprint. The annexed chambers are only accessible from within the mosque, not from the outside, through doors in the qibla wall. A public fountain with tile mosaic inside a horseshoe arch with carved stucco outlines is located across the street from the mosque. The fountain was built in the late 1800s and renovated in 1918 and 2003. The mosque’s walls are stuccoed white, with green and orange ceramic tiles added as ornamentation to the entrances and minaret’s surfaces. Green ceramic tile was also used to finish the mosque’s roof. The mosque’s main entrance, which is shaped like a rounded horseshoe arch, is massive in scale. Similar ornamental themes may be found on the minaret’s square main shaft, which also has green and orange ceramic tilework. The main shaft, which has a square plan of roughly four meters by four meters and is topped by stepped merlons, rises to four-fifths of the height of the minaret. Except for the colorful tilework inlaid on each elevation, the brick minaret is entirely coated in white stucco. The tilework is utilized as an infill for the blind arcades on each level of the shaft, which are delineated in relief. Only the third and fifth floors of the minaret have internal openings, and even those are mediated by stucco screens with a small-scale lozenge design that appears to be a continuation of the geometric patterns found in the tilework of larger blind arcades. The main prayer hall is three aisles deep and stretches from the courtyard to the qibla (direction of prayer) and mihrab (niche signifying the direction of prayer). A library, imam’s chamber, and a funeral mosque (for completing funerary rites before the burial of a person) are all located behind the mihrab wall at the far end of the mosque and may be reached from within the mosque. The Great Mosque of Tangier lost its cultural significance after the French occupied Morocco in the early twentieth century. The French built a nouvelle ville (colonial town) in Tangier in the 1920s, relocating the city center away from the Great Mosque and relegating it to a historical but no longer civic role.