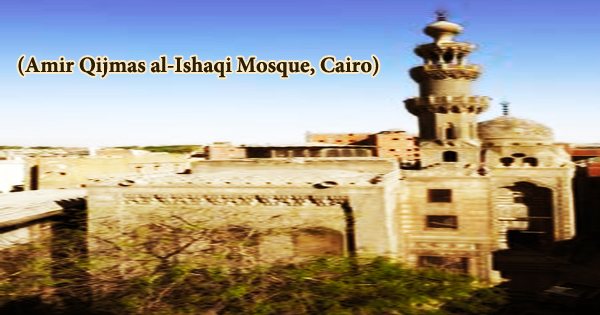

The Amir Qijmas al-Ishaqi Mosque (Arabic: مسجد قجماس الإسحاقي), also known as the Abu Hurayba Mosque (Arabic: مسجد أبو حريبة; sometimes written – Abu Heriba), was built in the El Darb El Ahmar district of Cairo, Egypt, near Souq Al Silah Street. Furthermore, Amir Qijmas al-Ishaqi was a powerful and well-known Prince and Sultan of Qaytbay, and he was attempting to acquire the plot on Al Tabbana Street in the El Darb El Ahmar district. Sultan Qaytbay’s stables were led by Amir Qijmas al Ishaqi. He had the mosque erected on a triangular land that dictated the irregular plan between 1479 and 1481. Many people see it as one of the best examples of late Mamluk architecture. The mosque was most likely started in the late 1470s and finished between 1480 and 1481. It was founded at a time when Cairo had already become extremely built-up, and finding a good place in the city to construct on required a lot of maneuvering. Qijmas al-Ishaqi, a prominent emir of Sultan Qaytbay, was able to obtain the land he desired on al-Tabbana street in the Darb al-Ahmar region through multiple acts of istibdal. The mosque of Qijmas managed to exhibit inventiveness in both its structure and its ornamentation at a time when the emphasis was on elaborate adornment rather than architectural innovation. Sayf al-Din Qijmas al-Ishaqi, a Burji Mamluk amir (commander) who served during Sultan Qaitbay’s reign, commissioned the mosque. He held various high-ranking roles, including amir akhur (officer in charge of the royal stables) and amir al-hajj (officer in command of the Hajj) (officer in charge of the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj). In 1470, he was named governor of Alexandria, and in 1480, he was named governor of Syria, a position he held until his peaceful death in 1487. Explore the Mosque and Tomb of Amir Qijmas al-Ishaqi with Flying Carpet Tours, as it was restored in the twentieth century, shedding light on a complex that was one of the most expensive and valuable jewels of Mamluk architectures, as its façade has ornate designs popular during Sultan Qaytbay’s reign. The Mosque of Abu Hurayba (or Abu Heriba, among other spellings) is named after Sheikh Abu Hurayba, a wali who died in 1852 and was interred in the domed mausoleum. The mosque is also famous for being depicted on the Egyptian 50-pound note.

The mosque did not just adapt the street contours; it took full control of them and incorporated them into its design. Given the mosque’s peculiar triangular plot, this was an architectural marvel in and of itself. The mosque’s interior design is both inventive and startling at times. The mosque is regarded as a noteworthy example of late Mamluk architecture, particularly due to the architect’s ingenious arrangement of the building’s various elements to fit them into an irregular plot of land at the intersection of El-Darb El-Ahmar Street and another lane connecting it to the north. With a muqarnas corbel and latticed windows, the main facade is crenelated. The entrance portal is enclosed within a trilobed groin-vaulted arch with ablaq brick decoration, and it appears on the right side of the facade with the minaret. It is one of the most ornately decorated mosques of the Qaytbay period, and the Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l’Art Arabe rebuilt it extensively in 1896. An elevated tunnel connects the mosque to a sabil-kuttab across the street. The mosque is built above stores that used to be on the street level and are now mostly underground, as is customary. The main part of the property is essentially formed like a right triangle, with an annex across the lane to the north and connected to the main structure via a raised walkway (sabat) above the street. Its decorative language, particularly in its mihrab, gateway, and abundant epigraphy, does not just adhere to the Qaytbay decorative repertoire; it has its own. The mosque’s anomalies, such as the minaret and dome, which were decorative misfits that appeared to have been left in an almost incomplete state, added to the intriguing nature of the mosque. The kuttab was moved from its regular location above the sabil to the opposite side of the street from the mosque. It features two main iwans (big chambers open to one side) to the west and east, as well as two smaller iwans to the north and south, including the qibla side (direction of prayer). Shops surround and are constructed into the base of the building, providing revenue for the mosque, while the mosque itself is raised above these and is accessed through a set of stairs. The mosque’s facade features highly refined embellishment that exemplifies Qaytbay’s superior architectural style. The whirling pattern on the circular marble medallion over the door is regarded exceptionally outstanding and unique. The entrance’s hardwood doors are adorned with beautiful bronze fittings. Metal knockers carved in an ornate design with two dragon heads used to adorn the doors (similar to a famous Anatolian example presently on exhibit in Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts), but they were stolen recently. Koranic inscriptions and an ablaq marble panel with black, white, and red leaf forms adorn the entry. The mosque’s flooring are paved with ornate marble (which is usually hidden by the mosque’s carpeting). Colored glass is fitted into plaster grilles in the windows. The presence of cypress tree patterns in the windows indicate the current stucco grilles were restored during the Ottoman period. Geometric sixteen-pointed star patterns emanate from circular bosses adorn the surfaces of the mosque’s hardwood minbar (pulpit). Rather from the deep carvings of earlier minbars, different colored inlays are used to give the ornamental effect. The mosque is a stunning architectural work that mainly focuses on the element of surprise, with unexpected features strewn about. In many ways, it is an extraordinary structure that not only followed but even outperformed the Qaytbay architectural style.