Using pieces taken from the gallstone of a corpse from the 16th century, an international team lead by scientists from McMaster University and working in partnership with the University of Paris Cité has found and rebuilt the first ancient genome of E. coli.

Today, the journal Communications Biology published the discovery online.

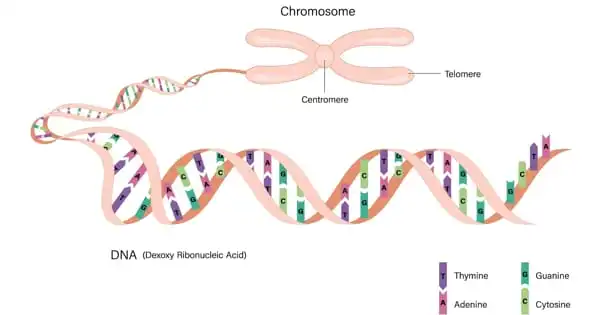

Despite being a significant cause of death and morbidity and considerable public health concerns, E. coli does not cause pandemics. It is referred to as a commensal, a type of bacteria that lives inside of us and can infect its host when there is stress, an underlying illness, or a lack of immunity. According to researchers, many details of its evolutionary history, such as when it picked up novel genes and antibiotic resistance, are still unknown.

Mummy, a body that has been embalmed, naturally preserved or prepared for burial using preservation techniques. Although the procedure varied from age to age in Egypt, it always entailed taking out the internal organs (although in the latter part of the civilization, they were replaced after therapy), treating the body with resin, and wrapping it in linen bandages.

There are no historical records of deaths brought on by commensals like E. coli, despite the impact on human health and mortality being undoubtedly enormous, unlike well-documented pandemics like the Black Death, which persisted for ages and killed as many as 200 million people worldwide.

“A strict focus on pandemic-causing pathogens as the sole narrative of mass mortality in our past misses the large burden that stems from opportunistic commmensals driven by the stress of lives lived,” says evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, who is director of McMaster’s Ancient DNA Centre and a principal investigator at the university’s Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

When we were examining these remains, there was no evidence to say this man had E. coli. Unlike an infection like smallpox, there are no physiological indicators. No one knew what it was.

George Long

There was a popular misconception that bitumen, which is derived from the Arabic term mimiyah and means “bitumen,” was used to prepare Egyptian mummies because it was thought to have therapeutic properties. A common item in pharmacy shops throughout the Middle Ages was “mummy,” which was created by pounding mummified remains.

Over time, it was forgotten that the bitumen in mummies was what gave them their virtue, and fake mummies were created using criminals’ and suicide victims’ bodies. Up to the 18th century, there was still a thriving mummy trade in Europe.

In the intestines of healthy humans and animals, modern E. coli is frequently found. While the majority of types are benign, a few of them can cause catastrophic, even fatal food poisoning outbreaks and bloodstream infections. It is known that the resilient and adaptive bacterium is particularly challenging to cure.

The genome of a modern bacterium’s 400-year-old ancestor offers researchers a benchmark for examining how it has changed and adapted since that time.

The well-preserved bodies of a group of Italian nobility whose mummified bones were used in the new study were found in the Abbey of Saint Domenico Maggiore near Naples in 1983.

One of the subjects, Giovani d’Avalos, was the subject of a thorough analysis by the researchers for the study. He was 48 when he passed away in 1586, and it is believed that gallstones caused his chronic inflammation of the gallbladder. He was a Neapolitan lord from the Renaissance period.

“When we were examining these remains, there was no evidence to say this man had E. coli. Unlike an infection like smallpox, there are no physiological indicators. No one knew what it was,” explains lead author of the study, George Long, a graduate student of bioinformatics at McMaster who conducted the analysis with co-lead author Jennifer Klunk, a former graduate student in the university’s Department of Anthropology.

E. coli is complicated and widespread, existing not just in the soil but also in our own microbiomes, making the technical achievement all the more impressive. The target bacterium had been damaged by environmental pollution from numerous sources, so researchers had to carefully extract parts of it. They rebuilt the genome using the recovered material.

“It was so stirring to be able to type this ancient E. coli and find that while unique it fell within a phylogenetic lineage characteristic of human commensals that is today still causing gallstones,” says Erick Denamur, the leader of the French team that was involved in the strain characterization.

“We were able to identify what was an opportunistic pathogen, dig down to the functions of the genome, and to provide guidelines to aid researchers who may be exploring other, hidden pathogens,” says Long.

The Canadian Institute of Advanced Research provided funding for the investigation, which was conducted in association with scientists from the University of Pisa and the Université Paris Cité/French Institute of Medical Research (INSERM).