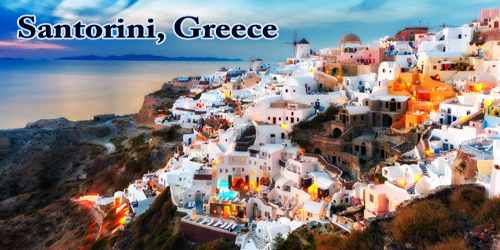

Santorini (Greek: Σαντορίνη, pronounced (sandoˈrini)), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα (ˈθira)) and classic Greek Thera (English pronunciation /ˈθɪərə/), is the supermodel of the Greek islands, a head-turner whose face is instantly recognizable around the world: multicolored cliffs soar out of a sea-drowned caldera, topped by drifts of whitewashed buildings. It is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast of Greece’s mainland.

Santorini is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago, which bears the same name and is the remnant of a volcanic caldera. It forms the southernmost member of the Cyclades group of islands, with an area of approximately 73 km2 (28 sq mi) and a 2011 census population of 15,550. The municipality of Santorini includes the inhabited islands of Santorini and Therasia, as well as the uninhabited islands of Nea Kameni, Palaia Kameni, Aspronisi, and Christiana. The total land area is 90.623 km2 (34.990 sq mi). Santorini is part of the Thira regional unit.

The islands that form Santorini came into existence as a result of intensive volcanic activity; twelve huge eruptions occurred, one every 20,000 years approximately, and each violent eruption caused the collapse of the volcano’s central part creating a large crater (caldera). The volcano, however, managed to recreate itself over and over again.

The last big eruption occurred 3,600 years ago (during the Minoan Age), when igneous material (mainly ash, pumice, and lava stones) covered the three islands (Thíra, Thirassiá, and Asproníssi). The eruption destroyed the thriving local prehistoric civilization, evidence of which was found during the excavations of a settlement at Akrotíri. The solid material and gases emerging from the volcano’s interior created a huge “vacuum” underneath, causing the collapse of the central part and the creation of an enormous “pot” today’s Caldera with a size of 8×4 km and a depth of up to 400m below sea level.

The eruption of the submarine volcano Kolúmbo, located 6.5 km. NE of Santorini, on 27th September 1650, was actually the largest recorded in Eastern Mediterranean during the past millennium! The most recent volcanic activity on the island occurred in 1950.

It is the most active volcanic center in the South Aegean Volcanic Arc, though what remains today is chiefly a water-filled caldera. The volcanic arc is approximately 500 km (310 mi) long and 20 to 40 km (12 to 25 mi) wide. The region first became volcanically active around 3-4 million years ago, though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around Akrotiri.

Santorini was named by the Latin Empire in the thirteenth century, and is a reference to Saint Irene, from the name of the old cathedral in the village of Perissa the name Santorini is a contraction of the name Santa Irini. Before then, it was known as Kallístē (Καλλίστη, “the most beautiful one”), Strongýlē (Greek: Στρογγύλη, “the circular one”), or Thēra. The name Thera was revived in the nineteenth century as the official name of the island and its main city, but the colloquial name Santorini is still in popular use.

Santorini’s commercial development is focused on the caldera-edge clifftops in the island’s west, with large clusters of whitewashed buildings nesting at dizzying heights, spilling down cliffsides, and offering gasp-inducing views from land or sea.

Fira, the island’s busy capital, sprawls north into villages called Firostefani (about a 15-minute walk from Fira) and Imerovigli (the highest point of the caldera edge, about a half-hour walk from Fira). A path running through these villages is lined with upmarket hotels, restaurant terraces, and endless photo opportunities.

These three conjoined settlements draw most visitors, together with the stunning and quite exclusive village of Oia in Santorini’s north. There’s a growing number of hotels in the island’s south, offering caldera views to the north and northeast. Akrotiri’s views come cheaper than Oia’s, but it’s a fair way from the action of Fira. Other famous smaller villages are Akrotíri and Méssa Vounó, with their famous archaeological sites, Pýrgos, Karterádes, Emporió, Ammoúdi, Finikiá, Períssa, Perívolos, Megalohóri, Kamári, Messariá, and Monólithos: some of the villages are cosmopolitan some more peaceful; they are surrounded by vast vineyards; whitewashed cliff-top towns with castles affording amazing views out over the Aegean.

Santorini is considered to be the most sought after place for a romantic getaway in Greece since there are not many places in the world where visitors can enjoy exquisitely clear waters while perched on the rim of a massive active volcano in the middle of the sea! The island has a growing reputation as a “wedding destination” for couples not only from Greece but from all over the world.

Santorini’s primary industry is tourism. Agriculture also forms part of its economy, and the island sustains a wine industry, based on the indigenous Assyrtiko grape variety. White varieties also include Athiri and Aidani, whereas red varieties include mavrotragano and mandilaria.

Santorini’s east coast is lesser known than the celebrated, elevated west coast. Here, the caldera-edge heights have sloped down to sea level, and volcanic-sand beaches and resorts offer a very different drawcard. East-coast resorts such as Kamari and Perissa have a more traditional (and more affordable) island-holiday appeal: sunlounger-filled beaches, water sports, bars, and taverna-lined promenades.

The east coast’s beaches are lined with black sand; on the south coast, there’s a string of beaches famed for their multicolored sand dramatic Red Beach is a traveler favorite. The island’s interior is dotted with vineyards and traditional villages that let you see beyond the tourist hustle. Make a stop in Pyrgos for great eats and a wander through charming backstreets.

Santorini has erupted many times, with varying degrees of explosivity. There have been at least twelve large explosive eruptions, of which at least four were caldera-forming. The most famous eruption is the Minoan eruption, detailed below. Eruptive products range from basalt all the way to rhyolite, and the rhyolitic products are associated with the most explosive eruptions. The earliest eruptions, many of which were submarine, were on the Akrotiri Peninsula, and active between 650,000 and 550,000 years ago. These are geochemically distinct from the later volcanism, as they contain amphiboles. Archaeological discoveries in 2006 by a team of international scientists revealed that the Santorini event was much more massive than previously thought; it expelled 61 cubic kilometers (15 cu mi) of magma and rock into the Earth’s atmosphere, compared to previous estimates of only 39 cubic kilometers (9.4 cu mi) in 1991, producing an estimated 100 cubic kilometers (24 cu mi) of tephra. Only the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815, the 181 AD eruption of Lake Taupo, and possibly Baekdu Mountain’s 946 AD eruption have released more material into the atmosphere during the past 5,000 years.

Santorini’s intrigue reaches deep into the past, with the fascinating site of Akrotiri displaying a Minoan city destroyed by the volcanic eruption of 1613 BC. In Fira, the impressive Museum of Prehistoric Thera helps piece together the story of ancient Akrotiri. Santorini was captured briefly by the Russians under Alexey Orlov during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 but returned to Ottoman control after. Following the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence on the Greek mainland in March 1821, in May Santorini followed suit, although the local Catholic population had its reservations. The island became part of the fledgling Greek state, rebelled against Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias in 1831, and became definitively part of the independent Kingdom of Greece in 1832, with the Treaty of Constantinople. The island is still home to a Catholic community and the seat of a Catholic bishopric. During the Second World War, Santorini was occupied in 1941 by Italian forces and in 1943 by those of the Germans. In 1944, the German and Italian garrison on Santorini was raided by a group of British Special Boat Service Commandos, killing most of its men. Five locals were later shot in reprisal, including the mayor.

The traditional architecture of Santorini is similar to that of the other Cyclades, with low-lying cubical houses, made of local stone and whitewashed or lime-washed with various volcanic ashes used as colors. The unique characteristic is the common utilization of the hypóskapha: extensions of houses dug sideways or downwards into the surrounding pumice. These rooms are prized because of the high insulation provided by the air-filled pumice and are used as living quarters of unique coolness in the summer and warmth in the winter.

Santorini’s lauded wines are its crisp dry whites and the amber-colored, unfortified dessert wine known as Vinsanto. Both are made from the indigenous grape variety, assyrtiko. About a dozen local vineyards host tastings (usually with a small charge) and some offer food, with scenery and local produce combining to great effect. Nature’s handiwork is on display from any waterfront seat come sundown, but prime sunset-viewing is in Oia, where thousands of tourists flock to admire (and applaud) nightfall.

Information Sources: