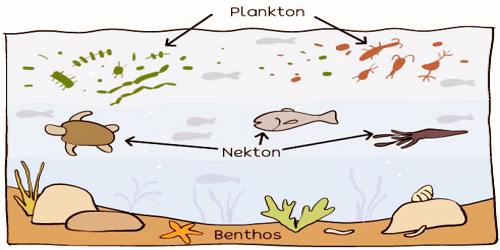

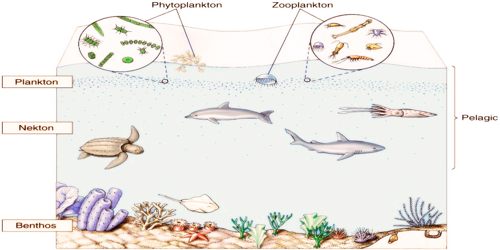

Nekton or necton, the assemblage of pelagic animals which swim freely, independent of water movement or wind, from the Greek nekton meaning “to swim”. In 1891, the German biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the concept to distinguish between the active swimmers in a body of water and the passive species borne by the plankton, the current. These species may be fish, shellfish, or mollusks living in an ocean or a lake. They appear to shift, without the current’s support. They are vertebrates, or creatures that have bones or cartilage, are strong swimmers in general and are larger than microbes.

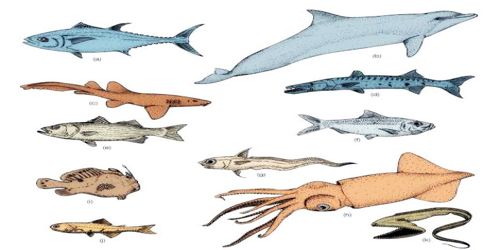

Nektonic organisms have a high number of Reynolds (greater than 1000) and planktonic organisms have a low number (less than 10) as a guideline. Only the adult forms represent three phyla. Several species of bony fish include chordate nekton, cartilaginous fish such as sharks, several species of reptiles (turtles, snakes, and saltwater crocodiles), and mammals such as whales, porpoises, and seals. However, some organisms can begin life as plankton and transition to nekton in a while in life, sometimes making distinction difficult when attempting to classify certain plankton-to-nekton species jointly or the opposite.

Molluscan necton contains squids and octopods. Decapods, including shrimps, crabs, and lobsters, are the sole arthropod nekton. Some biologists chose not to use the word for this purpose. The species in nekton can be contrasted with how plankton moves; however, the key difference is that necton creatures can move independently. Today it’s sometimes considered an obsolete term because it often doesn’t give the meaningful quantifiable distinction between these two groups. Some biologists not use it.

Although a few nearshore and shallow-water species subsist by grazing on plants, herbivorous nektons are not very common. Zooplankton feeders are the most numerous of the nektonic feeding groups and include some of the largest nekton, the baleen whales, in addition to many bony fishes, such as sardines and mackerel. As a suggestion, nekton is larger and have a tendency to swim largely at biologically high Reynolds numbers (>10³ and up beyond 10⁹), where inertial flows are the rule, and eddies (vortices) are easily shed. The molluscans, sharks, and plenty of the larger bony fishes consume animals bigger than zooplankton. Some fish are scavengers and most of the crustaceans. Nekton species often, when small, are similar to plankton and turn into nektons as they grow.

Plankton, on the opposite hand, is small and, if they swim the least bit, do so at biologically low Reynolds numbers (0.001 to 10), where the viscous behavior of water dominates, and reversible flows are the rule. The molluscans, sharks and many of the bigger bony fish eat species larger than zooplankton. Some fish are scavengers and most of the crustaceans. When they are very tiny and swim at low Reynolds numbers, species such as jellyfish and others are called plankton and called nekton as they grow big enough to swim at elevated Reynolds numbers.

Nekton organism

Nektonic organisms are limited in their area and vertical distributions by the barriers of temperature, salinity, nutrient availability, and form of the sea bottom. Many animals considered nekton classical examples (e.g., Mola mola, squid, marlin) to begin life as tiny plankton members, and then, it was argued, gradually move as they evolve to nekton. With increasing depth in the ocean, the number of nektonic organisms and individuals declines. There are species whose initial stage of life is known as planktonic but they become nectonic as they expand and increase in body size. A common example of this is the jellyfish medusa.

Information Sources: