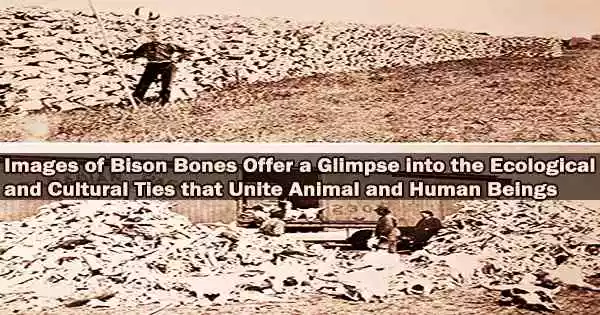

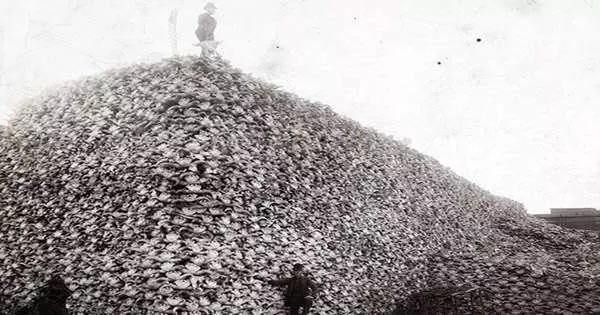

Due to changes in the planet’s ecosystems brought on by humans, we are currently experiencing a period of unparalleled species extinction. This is hardly the only instance in which human activity has fundamentally altered the interactions between land and life. The eradication of bison from the North American West in the 19th century is one important example of catastrophic species loss, which is illustrated by a well-known photograph of the bones.

As a visual studies researcher, I (Danielle Taschereau Mamers) use photographs to analyze the impacts of colonization on human and non-human lives. Images of bison bones provide a window into the cultural and ecological relations that tie animal and human lives together. Through photographs, we can also think about bison extermination as part of a history of relationships.

An iconic image

The most well-known depiction of bison extinction is a graphic one showing a mountain of bison skulls. It was taken outside of Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Mich., in 1892. There were between 30 and 60 million bison on the continent at the end of the 18th century. Only 456 wild bison remained in that population at the time of this shot.

Large-scale bison slaughter resulted from the West’s increased colonization. The killing increased as white settler hunters showed there with their guns and as the market for hides and bones grew. Most herds were exterminated between 1850 and the late 1870s.

The photograph shows the massive scale of this destruction. The pile of bones appears to be a man-made mountain rising from the grassy foreground of the picture. The photo serves as an illustration of “manufactured landscapes,” as Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has put it. What was taken from prairie land to make this manufactured landscape in Michigan?

The Rougeville photograph is often used to illustrate the scale of bison extermination. It can be found in current protest memes, movies, magazines, and books about conservation. The image has come to symbolize the slaying of this animal. But this image stands for more than just the destruction and hubris that humans are capable of. Using several glasses to examine the image reveals a history of connections.

The mound of skulls also indicates the abundance of bison life. But what was life on the Prairies like before bison extermination? What relationships did bison have before their deaths?

Human-bison relationships

We know that Indigenous Nations and bison herds were closely linked. The numerous bison herds helped to create big, politically and socially complex communities throughout the Prairies, which in turn affected the lives of Indigenous Nations. Numerous Indigenous scholars show the connection between the Native American tribes of the Plains and bison herds, often known as buffalo.

For example, Cree political scientist Keira Ladner studied the non-hierarchical organization of Blackfoot communities and practices of collaborative decision-making. These local customs have their origins in intimate ties to bison herds, which function as non-coercive groups in which no one animal predominates.

Similar to how the buffalo is described as a relative of Indigenous peoples of the Plains in the Buffalo Treaty, an Indigenous-led initiative to reintroduce wild bison that was originally signed in 2014. The treaty states: “Buffalo is part of us and we are part of buffalo culturally, materially and spiritually.”

Tasha Hubbard, a Cree scholar and filmmaker, has gathered accounts of the eradication of the bison from numerous Indigenous Peoples of the Plains. These tales lament the loss of bison, a non-human species that many Indigenous Nations view as relatives. Communities of Indigenous people and bison suffered gravely from extinction. According to Hubbard, killing bison constituted a type of genocide.

Through the lens of interrelationship, the photograph takes on additional meaning. As Dakota scholar Kim TallBear reminds us: “Indigenous peoples have never forgotten that non-humans are agential beings engaged in social relations that profoundly shape human lives.” The pile of skulls is not only symbolic of the destruction of an ecosystem. It is also a symbol of the loss of relations.

Multi-species relationships

Bison made the Prairies hospitable for many other communities. One 600-kilogram animal is represented by each skull. The largest terrestrial mammal in North America is the bison. In addition to their enormous size, bison are keystone species in the West, which means they have a significant impact on an ecosystem. When one of these species goes extinct, the ecosystem as a whole changes because no other species can take on that ecological role.

The skulls in the picture depict the destruction of an entire ecosystem as well as the extinction of bison. With every bison slaughtered, grazing, wallowing, and migration activities that make the habitat friendly for other species were put an end to.

For instance, bison dung contains hundreds of different bug species that serve as a food source for bats, turtles, and birds. Rolling in the ground causes depressions known as wallows, which fill with spring rain and house tadpoles and frogs. These and many other species would lose their habitats and food sources without bison.

Colonial capitalist relationships

The bison skulls are not alone in the photograph. Two suit-clad guys hold up the skulls in a triumphant gesture. Their presence denotes a different facet of human-animal relationships: those involving markets or commodities.

From all over the Prairies, each skull was gathered, packed, and sent by train or steamer to the east. Bison bones were converted into fertilizer, glue, and ash once they were received at businesses like Michigan Carbon Works. The bones produced commodities, like bone china, which were sold in European and North American cities. The big crate in the image’s foreground is an example of a colonial capitalism technology that was used to transport bones from prairies to factories and then finished goods to markets.

The image also depicts the infrastructure network that colonial settler agents erected throughout North America. The infrastructure built by settlers, including roads, railroads, factories, and markets, greatly accelerated the conversion of animals into commodities.

Colonial capitalism’s extractive industries wreaked havoc on habitat, biodiversity, interactions between bison, other plant and animal species, and Indigenous Nations. Similar businesses are responsible for the widespread extinctions that are currently occurring and are expected to continue soon.

Looking ahead

There are currently 31,000 wild bison living in conservation herds in North America. The species is considered “near threatened” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. This shows that while protections are still required, conservation measures have increased the possibilities of the bison species surviving.

These creatures are the offspring of the few hundred bison that escaped their extinction in the 19th century. With the help of conservation projects, including the Indigenous-led Buffalo Treaty and InterTribal Buffalo Council, bison continue to survive.

As can be seen from a close examination of the Rougeville shot taken from various angles, there has been a catastrophic loss of bison. The eradication of the animal in its wild, free-ranging form altered relationships on the Prairies for all time.