Lymphatic Vessel

Definition

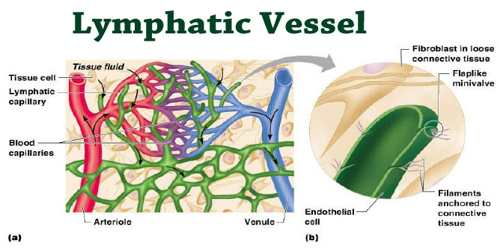

Lymphatic vessels are any of the vascular channels that transport lymph throughout the lymphatic system and freely anastomose with one another. It is also called absorbent vessel. As part of the lymphatic system, lymph vessels are complementary to the cardiovascular system. Lymph vessels are lined by endothelial cells, and have a thin layer of smooth muscles, and adventitia that bind the lymph vessels to the surrounding tissue.

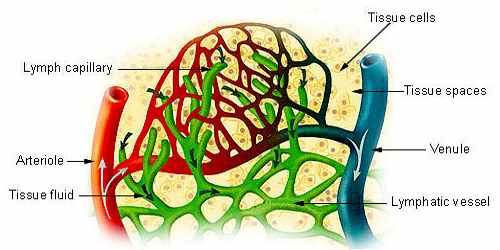

Our circulatory system consists of a pump (heart) and a network of tubes that conduct blood throughout our body (blood vessels). With each heartbeat, blood is forced into our arteries, which carry blood away from our heart and toward all of our tissues and organs. As our arteries travel farther from our heart, they divide into progressively smaller vessels called arterioles, which themselves divide into tiny, thin-walled, somewhat leaky vessels called capillaries.

Lymph capillaries are slightly larger than their counterpart capillaries of the vascular system. Lymph vessels that carry lymph to a lymph node are called the afferent lymph vessel, and one that carries it from a lymph node is called the efferent lymph vessel, from where the lymph may travel to another lymph node, may be returned to a vein, or may travel to a larger lymph duct. Lymph ducts drain the lymph into one of the subclavian veins and thus return it to general circulation.

Structure and Functions of Lymphatic Vessel

The general structure of lymphatic vessels is similar to that of blood vessels since these are the only two types of vessels in the body. While blood and lymph fluid are two separate substances, both are composed of the same water (plasma or fluid) found elsewhere in the body. There is an inner lining of single flattened epithelial cells (simple squamous epithelium) composed of a type of epithelium that is called endothelium, and the cells are called endothelial cells. This layer functions to mechanically transport fluid and since the basement membrane on which it rests is discontinuous; it leaks easily.

The next layer is smooth muscles arranged in a circular fashion around the endothelium that alters the pressure inside the lumen (space) inside the vessel by contracting and relaxing. The activity of smooth muscles allows lymph vessels to slowly pump lymph fluid through the body without a central pump or heart. By contrast, the smooth muscles in blood vessels are involved in vasoconstriction and vasodilation instead of fluid pumping.

The outermost layer is the adventitia, consisting of fibrous tissue. It is made primarily out of collagen and serves to anchor the lymph vessels to structures within the body for stability. Larger lymph vessels have many more layers of adventitia than do smaller lymph vessels. The smallest vessels, such as the lymphatic capillaries, may have no outer adventitia. As they proceed forward and integrate into the larger lymph vessels, they develop adventitia and smooth muscle. Blood vessels also have adventitia, sometimes referred to as tunica. The lymphatic circulation begins with blind ending (closed at one end) highly permeable superficial lymph capillaries, formed by endothelial cells with button-like junctions between them that allow fluid to pass through them when the interstitial pressure is sufficiently high.

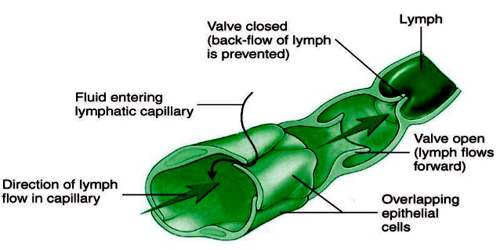

The lymph capillaries drain the lymph to larger contractile lymphatics, which have valves as well as smooth muscle walls. These are called the collecting lymphatics. As the collecting lymph vessel accumulates lymph from more and more lymph capillaries in its course, it becomes larger and is called the afferent lymph vessel as it enters a lymph node.

Lymphatic capillaries are designed to pick up the fluid that leaks into our tissues from our bloodstream and return it to our circulatory system. Nature has ingeniously devised our lymphatic and circulatory systems so the pressure in our blood capillaries is slightly higher than the pressure in our lymphatic capillaries. This pressure gradient from blood capillary to tissue to lymphatic capillary gradually moves fluid from our circulatory system to our lymphatic system, much like water in a river flows downhill.

Without valves, the lymphatic system would be unable to function without a central pump. Smooth muscle contractions only cause small changes in pressure and volume within the lumen of the lymph vessels, so the fluid would just move backwards when the pressure dropped. Blood vessels also have valves, but only in low pressure venous circulation. They function similarly to lymphatic valves, though are comparatively more dependent on skeletal muscle contractions.

Reference: