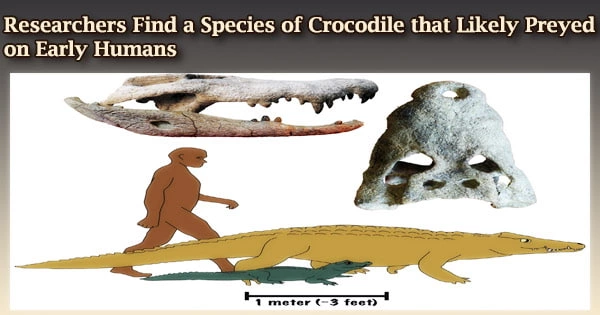

Our ancestors were prey to huge dwarf crocodiles that roamed a region of Africa millions of years ago. The tropics of Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Americas are home to crocodiles, which are enormous aquatic reptiles. Caimans, gharials, and alligators, which are also living members of the order Crocodilia but belong to different families, are morphologically and behaviorally different from true crocodiles.

Two new species of crocodiles that lived in east Africa between 18 million and 15 million years ago before inexplicably going extinct have been found, according to a recent study headed by experts at the University of Iowa. The enormous dwarf crocodiles are a species that are linked to the dwarf crocodiles that are currently found in central and west Africa.

However, the enormous dwarf crocodiles were far larger than their current counterparts, hence the moniker. Rarely can dwarf crocodiles grow longer than 4 or 5 feet, but their prehistoric ancestors could reach lengths of up to 12 feet, making them among the most dangerous threats to any animals they came across.

“These were the biggest predators our ancestors faced,” says Christopher Brochu, professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Iowa and the study’s corresponding author.

“They were opportunistic predators, just as crocodiles are today. It would have been downright perilous for ancient humans to head down to the river for a drink.”

Kinyang mabokoensis and Kinyang tchernovi are the names of the new species. They had big, conical teeth and short, deep snouts. Instead of opening straight upward like modern crocodiles, their noses opened somewhat up and to the front. Instead of being in the water, they waited for prey by spending the majority of their time in the forest.

Modern dwarf crocodiles are found exclusively in forested wetlands. Loss of habitat may have prompted a major change in the crocodiles found in the area. These same environmental changes have been linked to the rise of the larger bipedal primates that gave rise to modern humans.

Professor Christopher Brochu

“They had what looked like this big grin that made them look really happy, but they would bite your face off if you gave them the chance,” Brochu says.

In the early to middle Miocene, when the area was primarily covered in forests, Kinyang lived in the East Africa Rift Valley, in sections of modern-day Kenya. But both species seemed to disappear starting around 15 million years ago, towards the conclusion of a period known as the Miocene Climatic Optimum.

Why did they vanish?

Brochu believes that less rain fell in the area as a result of climate change. As a result of the decrease in rainfall, forests gradually disappeared and were replaced by grasslands and mixed savanna woodlands. Kinyang was impacted by the alteration in the landscape because, according to the researchers, it likely favored woodland areas for nesting and hunting.

“Modern dwarf crocodiles are found exclusively in forested wetlands,” says Brochu, who has studied ancient and modern crocodiles for more than three decades.

“Loss of habitat may have prompted a major change in the crocodiles found in the area. These same environmental changes have been linked to the rise of the larger bipedal primates that gave rise to modern humans,” Brochu adds.

As the researchers are unable to pinpoint the exact moment the animals went extinct, Brochu agrees that more research is necessary to establish what caused the Kinyang to go extinct. The fossil record also shows a divide between KInyang and other crocodile lineages that appeared around 7 million years ago.

Relatives of the Nile crocodile now residing in Kenya were among the latest arrivals. In multiple trips to Nairobi’s National Museums of Kenya since 2007, Brochu has inspected the specimens.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Leakey Foundation, the Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, the Fulbright Collaborative Research Program, the Boise Fund of Oxford University, the IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group, the University of Iowa, the Karl und Marie Schack-Stiftung Fund and Vereinigung von Freunden und Förderern der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, and the Ministerio de Universidades de España.