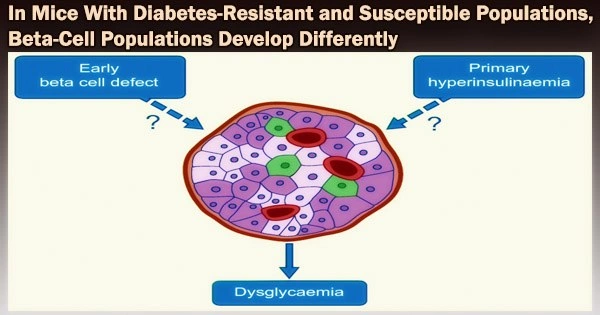

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterized by the progressive malfunction and failure of insulin-releasing beta cells. Researchers at DZD have now demonstrated that mice with and without diabetes react differently to a diet high in carbohydrates.

The diabetes-resistant mice’s beta cells’ gene expression altered in such a way that a protective beta cell cluster emerged. Failure to alter gene expression in response to rising blood glucose levels enhanced metabolic stress and beta cell degeneration in diabetic-prone animals. The study was published in the journal Diabetes.

Researchers at the DZD carried out single-cell RNA sequencing of the islets of Langerhans in two obese mouse strains that vary in their susceptibility to diabetes in order to examine the processes of beta cell loss in T2D.

Six distinct types of beta cells, which are similarly abundant before treatment, are present in the islets of both the diabetes-prone and diabetes-resistant mice. However, the beta cell cluster composition varied considerably between the strains following two days of consuming a high-carbohydrate, diabetogenic diet.

Our study provides new clues as to why obesity does not always lead to type 2 diabetes. The ability of mice, and presumably humans as well, to respond to elevated blood glucose levels with a transient reduction in their beta cell identity appears to play a key role in protecting them from loss of function and/or apoptosis.

Annette Schürmann

The islet cells of the diabetes-resistant mice developed into a protective beta cell cluster (Beta4). This protective cluster showed indications of reduced beta cell identity (such as downregulation of the GLUT2, GLP1R and MafA genes). Characteristics of mature beta-cell expression decreased. This most likely causes a decrease in glucose uptake and, for some, a rise in the capacity to divide, which will result in the production of more beta cells.

An in vitro knockdown of GLUT2 in beta cells led to reduced stress reactions and a decrease in apoptosis markers (apoptosis = programmed cell death). This could explain the improved survival of beta cells in diabetes-resistant mice.

In contrast, beta cells from mice predisposed to diabetes reacted by changing their expression, which is a sign of stress and metabolic load in the endoplasmic reticulum. A more dedifferentiated state of gene expression was also lacking in them. This may contribute to the loss of beta cells that will occur later, which will then lead to the onset of diabetes.

“Our study provides new clues as to why obesity does not always lead to type 2 diabetes. The ability of mice, and presumably humans as well, to respond to elevated blood glucose levels with a transient reduction in their beta cell identity appears to play a key role in protecting them from loss of function and/or apoptosis,”said Annette Schürmann, lead author of the study.

About the study

Researchers from the German Center for Diabetes Research, Helmholtz Munich and the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus and the Medical Faculty of TU Dresden were involved in the study, which was led by the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE).