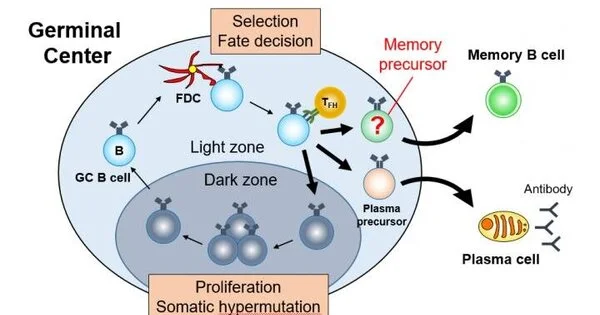

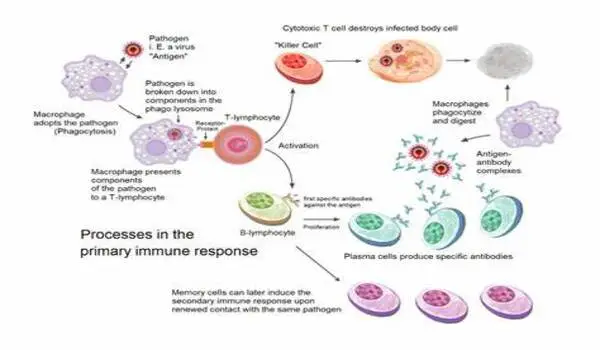

Unexpected insights have emerged on how and when particular infection-killing white blood cells select to create memory about their interactions with a virus. For decades, researchers have known that these cells can transform into long-lasting memory cells after an original infection has been cleared. They are prepared to promptly detect and remove future incursions by the same disease.

This is one of the reasons why people are resistant to some infectious diseases after being exposed to or recovering from them. Vaccines also work in this manner, teaching the immune system to recognize and kill harmful viruses, parasites, and bacteria.

Scientists from UW Medicine and the University of Washington, together with partners, wanted to know exactly when cytotoxic T lymphocytes, a type of immune white blood cell that directly destroys infected cells, decide to establish memory throughout an infection. They used real-time, live imaging to follow the progression of these cells throughout their history.

Our experiments revealed an unexpected degree of flexibility in memory decision making, whereby memory T cells are generated at multiple phases during the immune response. After encountering a pathogen, T cells decide early whether to form a memory, or alternatively, to become an effector cell, which has potent cell-killing abilities but is short-lived.

Dr. Abadie and Clark

Their findings have been published in the journal Immunity by Cell Press. Kathleen Abadie and Elisa Clark, both National Science Foundation graduate fellows, recently completed their training in the laboratory of senior author Hao Yuan Kueh, a UW associate professor of bioengineering, a joint department in the College of Engineering and School of Medicine.

“Our experiments revealed an unexpected degree of flexibility in memory decision making, whereby memory T cells are generated at multiple phases during the immune response,” the research team wrote. “After encountering a pathogen, T cells decide early whether to form a memory, or alternatively, to become an effector cell, which has potent cell-killing abilities but is short-lived.”

They added, however, that after the pathogen is eliminated, effector cells can, in essence, change their minds and decide late to join the memory cell pool. Additionally, the researchers examined the molecular switch that underlies flexible memory formation in these cells. They learned that this switch acts on the key memory regulatory gene Tcf7.

“This switch can turn off Tcf7 early in response to stimulatory signals due to infection,” they explained. “However, importantly, this switch is reversible when these signals are gone, thus enabling cells that have gone down the effector trajectory to reverse their course.”

Why do T cells need leeway in their memory decisions?

“For humans,” Abadie noted, “having some degree of flexibility to change their minds after decisions have been made allows individuals to better adapt to uncertain and changing circumstances.”

The same might be true for T cells to respond effectively to different threats.

According to the researchers, an analysis of a mathematical model of T cell decisions demonstrates that this flexibility allowed memory to form for both virulent pathogens that require a large-scale immune response and slow-dividing pathogens that do not try to overwhelm the immune system but rather attempt to evade it.

“The ability to make memory fate decisions at multiple junctures during an infection might also allow for greater responsiveness during the evolving situation of an immune challenge,” according to the researchers.

According to Abadie and Clark, these kinds of investigations could finally answer the long-standing question of how and when memory cells develop. They anticipate that the findings may lead to new areas of research into improving long-term immune protection against a number of infectious illnesses and malignancies.